Simone Casey, RMIT University and Liss Ralston, Swinburne University of TechnologyMany Australians whose jobs were decimated by the COVID business shutdowns will soon be waking up to new income shocks and the prospect of rental stress. This is because people whose employers can’t afford to keep them on will suddenly lose more than A$300 per week when the JobKeeper scheme ends on March 28. Worryingly, this income shock will happen just days before the payment to people on the JobSeeker benefit is effectively cut by $100 per fortnight.

At that point, all income support recipients – more than 2.6 million people – will be below the poverty line and many will face extreme rental stress.

Read more:

$1 billion per year (or less) could halve rental housing stress

This income shock has been anticipated for some time, but what does it means for rates of rental stress, particularly in Victoria? Despite promising signs of recovery, Victorian jobs lost in the COVID-induced recession, such as in the hard-hit business tourism and live music industries, have not bounced back at the same rate as others.

What will happen to rental affordability?

To illustrate this point we have modelled housing affordability for single people who were on either the full-time or part-time JobKeeper rate. In this scenario, they could also get JobSeeker payments at a part-rate because of the temporary increase in the income-free threshold to $300. This made them eligible for Commonwealth Rent Assistance too.

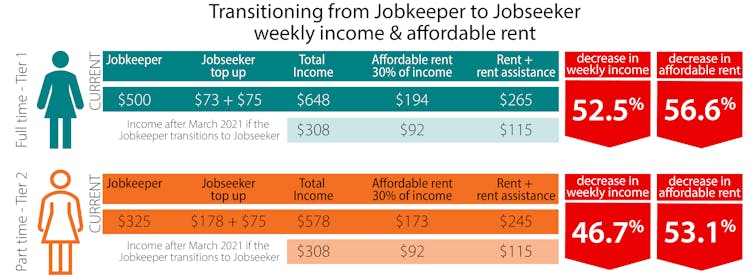

The chart below shows the impacts on income and rental affordability when JobKeeper and Coronavirus Supplement payments end. Their incomes and the amount of rent they can afford are roughly halved.

Author provided

Full-time and part-time single workers were able to afford weekly rent of $265 and $245 respectively before the withdrawal of JobKeeper. Afterwards, affordable rent goes down to $115 per week. That’s about $110 less than the $450 median rent ($225 per person) for a two-bedroom share house in Melbourne.

Based on our earlier calculations, this leaves these renters with only $17.57 per day to meet basic costs. They have a lavish $3.57 per day more than they did before the pandemic to pay for food, utilities and job-seeking costs such as mobile phone plans and travel cards (A$4.40 a day in Melbourne).

Read more:

City share-house rents eat up most of Newstart, leaving less than $100 a week to live on

What is different now than for pre-COVID unemployment was that business shutdowns thrust people who had reliable earnings – and accompanying high rents and mortgages in metropolitan areas – onto JobSeeker and JobKeeper payments.

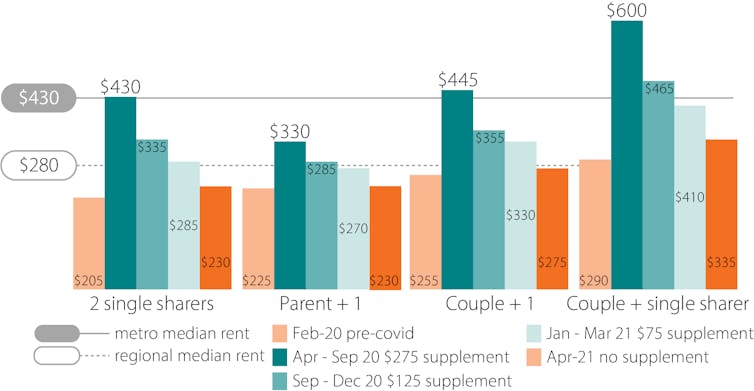

The chart below shows the change in rental affordability for a number of household types before the pandemic and during the Coronavirus Supplement stages (i.e. payments of $550, then $250, then $150).

For example, when their income was highest during the $550 stage, two singles sharing could afford rent of $430 per week. Once the supplement ends and is replaced by the $25-a-week increase in JobSeeker payment, affordable rent declines to only $230 per week or $115 each.

Rental affordability for single-parent households is notable here because the COVID Supplement was payable to one person only. Once the supplement is withdrawn, they will again be disadvantaged relative to other households because they will not be receiving the increase in the JobSeeker payment.

Read more:

After COVID, we’ll need a rethink to repair Australia’s housing system and the economy

What sort of job losses can we expect?

It is hard to predict exactly how many people will lose their jobs when JobKeeper ends. What we do know is the economic recovery in Victoria has lagged behind the other states. We also know that at the end of December 2020 1.55 million people were on JobKeeper and a large proportion of them (626,000) were in Victoria.

Economist Jeff Borland conservatively estimates national job losses could range between 125,000 and 250,000. It is reasonable to expect as many as half of these could be in Victoria.

Our analysis also shows there are worrying signs that the economic recovery celebrated in the January labour force data was not sustained in February. The latest data provided to a Senate inquiry into COVID-19 show JobSeeker recipients increased by 7,267 between January and February. The increase in Victoria could be attributed to the temporary Christmas retail boom, but in states like New South Wales and Queensland claims decreased slightly.

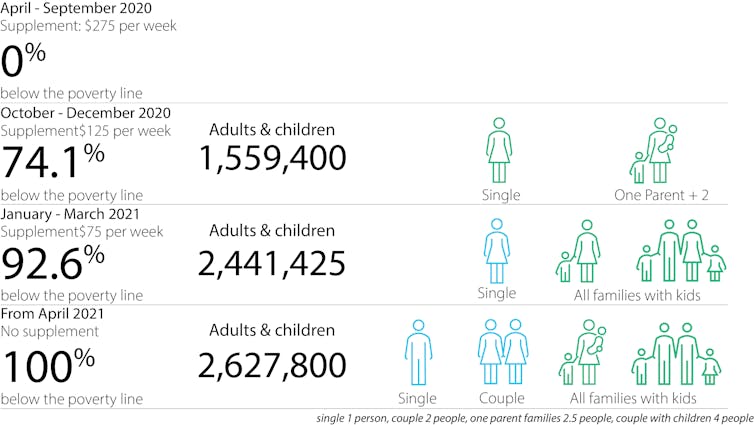

While fewer people will lose their jobs in other states than in Victoria when JobKeeper is withdrawn, they are not immune to this income shock. We created the chart below to show the overall scale of the coming problem of rental stress when the fortnightly $150 Coronavirus Supplement disappears and is replaced by the $50 JobSeeker increase.

Once the supplement reduced to $250 per fortnight, singles and single parents with two children were below the poverty line. When it was reduced to $150, the number of household types in poverty increased again. From April 1, all income support recipients – covering more than 2.6 million people including children – will be waking up to poverty and the prospect of extreme rental stress.

What can be done to avoid this?

So how can governments prevent people from falling off the rental cliff? It is unlikely to be achieved by introducing cut-price flights to Far North Queensland.

A new range of strategies will be needed. These include options advocated by ACOSS and others to increase the maximum rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance by 50%, increase the JobSeeker base rate above the poverty line and introduce rental stress grants targeted at individuals who need help.

Over the longer term, there is also a need to adopt strategic approaches to increase the supply of affordable rental housing such as those recommended by researchers at the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).![]()

Simone Casey, Research Associate, Future Social Service Institute, RMIT University and Liss Ralston, Adjunct associate, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.