Greg Barton, Deakin UniversitySpoiler alert: we are not winning the global war on terror. If the past 20 years of fighting terrorism by military means have shown us anything, it is that going to war makes things worse.

The direct costs in terms of human suffering – lives lost, societies destroyed and trillions of dollars spent – are multiplied by unintended consequences and cascading problems.

Invading Iraq in 2003 created a vacuum quickly filled with violent insurgencies that led directly to the rise of Islamic State and indirectly to a devastating decade of civil war in Syria. It did not make sense at the time and it certainly does not make sense now.

Launching a military campaign in Afghanistan weeks after the attacks of September 11, however, started out looking like a sensible response. Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda had planned and directed the attacks from the mountains of eastern Afghanistan.

It was there in the late 1980s, during the struggle of the Afghan mujahideen against the Soviet military, that al-Qaeda – “the base” – had been formed to support foreign mujahideen. The mission was to further radicalise and equip them to take jihad to the world.

The initial US special forces operation, which then Prime Minister John Howard insisted Australia join, had the goal of capturing or killing bin Laden and the al-Qaeda leadership. It also aimed to deny al-Qaeda a safe haven in Afghanistan to launch further attacks.

The Taliban regime that had come to power in Kabul five years earlier chose to protect al-Qaeda and suffered the consequences. Mullah Baradar and other Taliban leaders yielded power in Kabul in November, much more quickly than anyone had anticipated. They then staged a strategic retreat to insurgent mode.

Read more:

World politics explainer: The twin-tower bombings (9/11)

In 2002, mission creep saw an international coalition doing what many said should have been done a decade earlier when the Soviets left. For a moment, nation-building seemed to be working, but then attention turned to invading Iraq.

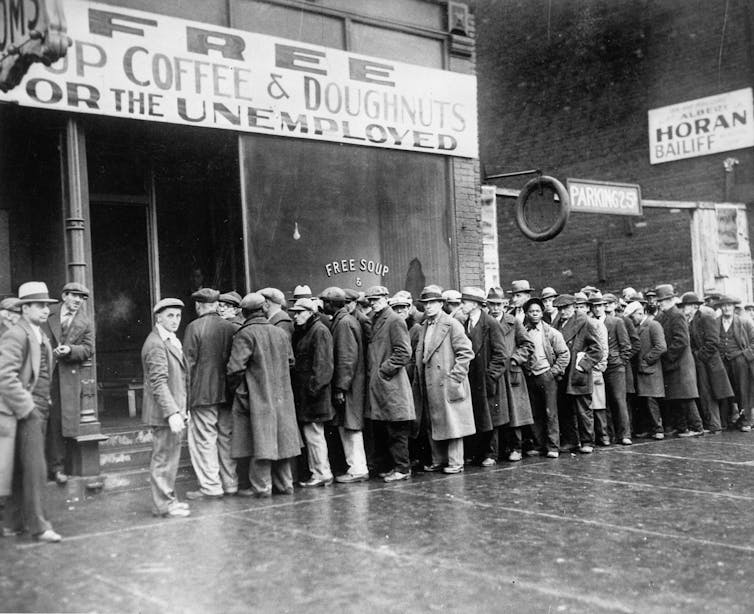

John Moore/AP/AAP

Even without the distraction of marching on Baghdad and sinking into a rapidly expanding quagmire of our own making, pretty much every mistake in counter-insurgency and nation-building that could be made in Afghanistan was made. A brittle, corrupt, incompetent and highly centralised government in Kabul presented opportunities on all fronts to the Taliban insurgency.

Even after a massive military surge early in the second decade of the 21st century that saw 140,000 International Security Assistance Force NATO troops enter the conflict, the patient Taliban remained. Then, after the sharp drawn-down of international troops in 2014, the Taliban insurgency expanded.

Long story short, the war on terror, and fighting terrorism by military means, has been a largely unmitigated failure. Even in Africa, where failing states and jihadi insurgencies have demanded military responses, victories have been short-lived. At best, as in Somalia, they have resulted in costly stalemates.

Read more:

Afghanistan: assessing the terror threat in the west as the Taliban returns

Military interventions have been costly and counter-productive

This is not to say the struggle against global terrorism has been completely without result. Elaborate terror plots targeting cities around the globe, first by al-Qaeda and then by IS, have been defeated and prevented on an impressive scale. But this has been achieved primarily by police-led counter-terrorism intelligence operations, working with communities, intercepting communications in terrorist networks and disrupting plots.

Military successes, such as the destruction of the IS caliphate in Syria and Iraq, have come not only at enormous cost, but also as corrections to problems created by military interventions.

Now in Afghanistan there is only failure. Two decades of significant achievement in transforming Afghan society, if not building robust government, have been washed away.

Not only that, the original success in defeating jihadi terrorism is also at an end, with the return of the Taliban and the success of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan project.

Developments in Afghanistan will be significant for at least three key reasons.

First, the triumph of the Taliban after two decades of struggle against the combined forces of NATO and the US is being seized on as evidence of divine approval for the global jihadist cause.

Ironically, although declaring a global war on terror proved to be a monumental mistake, jihadi movements such as al-Qaeda, the Taliban and IS are defined by their commitment to what they claim to be a holy war. That is why the success of Taliban, after 20 years of struggle, resounds around the world. And that is why, for all of their post-victory rebranding and social media information campaign, the Taliban, as a jihadi movement, remains bound to al-Qaeda.

Second, the mountains of Afghanistan will once again become home to mujahideen from across Asia and around the world. Jihadi camps in Afghanistan will return to making a significant contribution to the recruitment, radicalisation, training and networking of new generations of jihadi fighters and movements in South-East Asia.

AAP/Australian Department of Defence handout

The Taliban regime in Kabul (or Kandahar) will, despite the Taliban’s existential commitment to global jihad, likely seek to distance itself from such camps. It will exploit plausible deniability, as it focuses on rehabilitating and reinventing its international reputation and securing the long-term viability of the Islamic emirate. This will potentially have the not insignificant benefit of restraining the Taliban from some of the brutal excesses of the past, particularly with respect to the oppression of women and the persecution of minority groups like the Hazara.

Read more:

As the Taliban surges across Afghanistan, al-Qaeda is poised for a swift return

But it will also contribute to a third, more insidious challenge. As world powers like China and Russia, neighbours like Iran and Pakistan, and Muslim nations like Indonesia and Malaysia seek to engage with the emirate in order to moderate the Taliban regime, local Islamist groups will exploit the opportunity to push the boundaries of the permissible in South-East Asia. This is already on display with statements congratulating “our brothers the Taliban” from radical Islamist political groups such as the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS).

The threat in southeast Asia

Over the past two decades, jihadi extremism with origins in the Afghan alumni – mujahideen trained and radicalised in Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s, and groups formed in Afghanistan such as Jemaah Islamiyah and the Abu Sayyaf Group – has been foundational to violent extremism in our region. This was amplified by a new generation of South-East Asian mujahideen returning from Syria and Iraq.

The stage is set for a new era of terrorist growth in South-East Asia and around the world. The IS motto of “remaining and expanding” rang hollow in the wake of the destruction of the caliphate.

Now, as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is set to eclipse the caliphate in scale and longevity, the jihadi catch-cry appears to have been met with divine vindication.![]()

Greg Barton, Chair in Global Islamic Politics, Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.