Tag Archives: protests

Thailand

Coronavirus Update: Global

Coronavirus Update: Australia

Coronavirus Update: Australia

As protests roil France, Macron faces a wicked problem — and it could lead to his downfall

CHRISTOPHE PETIT TESSON/EPA

Peter McPhee, University of Melbourne

Two years ago, the streets of France were filled with the gilets jaunes (yellow vests), a grassroots protest movement sparked by a proposed tax hike on petrol.

Though they have shed their yellow safety jackets, many of these disaffected people have joined a new wave of protests that has roiled France for weeks, presenting a major challenge for the government of President Emmanuel Macron.

The protests erupted in late October after the horrific murder of the schoolteacher Samuel Paty, who had used caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad during a lesson. Thousands marched in tribute to Paty, but also in support of freedom of speech.

In the past month, protesters have also taken aim at a proposed new security law intended to combat what the government describes as “Islamic radicalism”. Nearly 150 people were arrested last weekend after protests became violent.

CHRISTOPHE PETIT TESSON/EPA

The roots of Macron’s current challenge

An explanation of the tensions connecting these protests takes us deep into the history of France, as well as to contemporary crises. It also suggests that there is no simple solution.

In 1789, French revolutionaries sought to capture their twin aspirations of religious tolerance and freedom of speech in articles 10 and 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen.

Read more:

For French Muslims, every terror attack brings questions about their loyalty to the republic

“No man may be harassed for his opinions, even religious ones”, they insisted, while asserting that “the free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious rights of man”.

Should these natural rights be curtailed in any way? Yes, of course: as article 4 stipulates, they would be limited to “ensure the enjoyment of the same rights for other members of society”. As to how this would be achieved, “only the law may determine these limits”.

Therein lay the problem. Since “the law” would be made by national legislatures, these limits would always be instrumental — that is, made by elected politicians working within a social and political context. That is Macron’s wicked problem today.

Francois Mori/AP

The continuing debate over laïcité

Conflict over limits to freedom arose immediately between revolutionaries and their opponents after 1789. There were ribald, even pornographic, attacks on Marie-Antoinette and the Catholic Church, reflecting a deadly schism between secular, republican France and the church.

For republicans, a central legacy of the revolution has been the principle of laïcité, that is, of a secular public space.

Freedom of religion has been guaranteed in France so long as it does not disturb public order. Religion is seen as a private matter and its observance strictly separated from public life.

This is a deeply held conviction in France. It explains the 2010 law that bans the wearing of full-face coverings in public, including but not limited to burqas and niqābs.

Michel Euler/AP

French supporters of laïcité would find it perplexing, if not offensive, to see one Australian prime minister, Kevin Rudd, holding Sunday press conferences outside his church, or another, Scott Morrison, welcoming the media inside his church and describing secular events (such as an election victory) as a “miracle”. In France, this might end political careers.

Australian and US commentators have been too ready to criticise France for not being as accepting of difference as their own societies, ignoring France’s different history and present.

Read more:

France’s laïcité: why the rest of the world struggles to understand it

From 1789, Jews, Protestants, Muslims — as well as Catholics — were guaranteed the freedom to worship, but the fine line between religious freedoms and secular public space has always been blurred, sometimes with tragic consequences.

Take Captain Alfred Dreyfus’s false conviction for treason in 1894, followed by his imprisonment and eventual exoneration in 1906. This was profoundly polarising because it embodied the violent divisions in France about the place of Jews in public life at a time of acute anti-semitism.

Dreyfus’s anti-semitic and anti-republican accusers included many clergy

— one of the reasons behind the formal separation of church and state in 1905.

Wikimedia Commons

Deep national tensions over Islam

Similarly, the beheading of Paty and subsequent terror attack in Nice in late October sparked a profound response because they occurred amid deep national tensions over the place of Muslims in France.

These tensions go back to wars of decolonisation in the 1960s, but were heightened by recent attacks at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and the Bataclan theatre in 2015.

SEBASTIEN NOGIER/EPA

While almost all Muslim organisations in France were prompt and unequivocal in repudiating those murders, elsewhere in the Muslim world, some were hostile to the freedoms accorded to media outlets such as Charlie Hebdo to publish caricatures mocking Islam and its prophet.

Leaders in Turkey, Morocco, Pakistan, Egypt and elsewhere condemned the magazine and called for consumer boycotts of French products.

Charlie Hebdo’s defence was that it mocks everybody, and it followed with an obscene cartoon of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Read more:

Liberty, equality, fraternity: redefining ‘French’ values in the wake of Charlie Hebdo

Macron has insisted the respect due to all religions must be balanced by the right to freedom of expression, no matter how offensive some caricatures might be to people of faith.

He has defended the right of Charlie Hebdo to publish the caricatures, even though some might be banned in other countries as deliberately offensive, even racist. While France has anti-hate laws, its highest courts have also been very reluctant to penalise satire.

At the same time, Macron’s minister of national education, Jean-Michel Blanquer, has targeted “Islamo-gauchisme”, the supposed undermining of French republican values by left-wing academics and intellectuals infected by feelings of guilt for France’s colonial past.

Can Macron find a solution?

These tensions have now spilled onto the streets in unanticipated ways, as they have become embroiled with deep anxieties and divisions about decolonisation, policing and the limits to secularism. All of this comes at a time of economic despair and strident criticism of the government’s mishandling of the pandemic.

In this context, violent police raids and a sweeping national security law, which would make a criminal offence to publish photos or film identifying police officers and expand police surveillance powers, have sparked widespread discontent.

In early December, the Macron government announced a revision of the security bill. This alone will not staunch a profound crisis of confidence in the foundational values of the republic: secularism, freedom of speech and respect for religious plurality.

In such a situation, the siren calls of cultural stereotyping may become louder, and Macron may need a “miracle” of his own to keep France out of the hands of Marine Le Pen and her Rassemblement National (National Rally), formerly known as the Front National, at the presidential elections of April 2022.![]()

Peter McPhee, Emeritus professor, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Protests have been criminalised under COVID. What is incitement? How is it being used in the pandemic?

Scott Barbour/AAP

Maria O’Sullivan, Monash University

The Victorian government is taking a hard line against protests as it tries to get COVID-19 under control. As Premier Daniel Andrews said on Thursday,

it’s not the time to protest […] regardless of what you’re protesting about.

In this climate, several people have recently been charged with incitement in relation to “anti-lockdown” protests in the state.

So, what is incitement? And what makes it so complicated during a pandemic?

What is incitement?

The offence of “incitement” criminalises behaviour that encourages others to commit a crime before the crime takes place.

Interestingly, the incitement need not be acted on for an offence to be committed. So it is enough, in the context of say, murder, that the “inciter” encourages another person to commit murder, even if that crime does not actually take place.

Read more:

Can the government, or my employer, force me to get a COVID-19 vaccine under the law?

Using the Victorian Crimes Act as an example, prosecutors must establish, beyond a reasonable doubt, that

- the accused person incited another to do something that would result in the commission of a criminal offence

- and at the time of the conduct, the accused had an intention that the offence would occur.

The meaning of “incitement” in legislation is very broad. For instance, the Victorian Crimes Act defines “incite” as to command, request, propose, advise, encourage or authorise.

What has been happening in Victoria?

This week, Victoria Police reported one man had been charged with incitement, following an alleged anti-lockdown gathering in Melbourne last weekend.

Additionally, and more controversially, a number of people have been arrested for incitement in relation to planned protests.

Erik Anderson/AAP

In a high-profile example, a pregnant woman was arrested in relation to a social media post, which allegedly encouraged people to attend a protest in Ballarat this weekend.

Three men have also been charged with incitement over allegedly coordinating a “Freedom Day” protest in Melbourne on Saturday.

These charges were also made in a different context back in April. Then, protesters staged a car convoy in Melbourne to highlight the plight of refugees. The organiser of the protest was arrested in his home under the charge of incitement, and again, before the protest had begun.

What is significant about these charges?

The application of incitement to protest is controversial for two main reasons.

Firstly, incitement is normally linked to the commission of a serious crime, such as murder or assault. The act of protest is not, of itself, a crime.

Secondly, breaching COVID restrictions is an offence under public health legislation and can lead to the issuing of a fine. But charging someone with incitement makes this an offence under the Crimes Act.

Read more:

Is protesting during the pandemic an ‘essential’ right that should be protected?

This can lead to much more serious punishment – such as imprisonment and, importantly, the recording of a criminal conviction. This may have serious consequences for a person’s employment, if they have a criminal record.

The complexity of COVID

Because of the very serious nature of the charge of incitement, it has very rarely been used in relation to protest. This is because normally, protesting is not of itself a criminal offence.

In ordinary circumstances, protesting would only be considered a crime if protesters damage property, commit trespass or pose a threat to public order.

David Crosling/AAP

For example, climate change activists in Queensland were recently charged with a number of offences, including using a dangerous attachment device to interfere with transport infrastructure and trespassing on a railway (their convictions were thrown out on Wednesday).

Using incitement to protest under COVID is particularly complex, because the use of such a criminal charge for a breach of a public health restriction is unclear. The complication is that under a state of emergency, various “normal” activities, such as organising public gatherings and assembling in public places, are subject to a penalty.

Read more:

Explainer: why is the Victorian government extending the state of emergency, and is it justified?

The application of incitement to protest during COVID is also messy as there is a significant lack of clarity about what some terms mean in Victoria’s stay at home directions. For instance, can protest be seen as an “essential” activity for the purpose of the directions? I have argued elsewhere that is should.

New territory

The use of incitement for protest under COVID poses new and complex legal questions.

These may well be tested in courts in time to come. Until then, Victorians under COVID need to look at incitement in a very different manner than before.![]()

Maria O’Sullivan, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, and Deputy Director, Castan Centre for Human Rights Law, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Grattan on Friday: Protests add new element of uncertainty to COVID exit

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

Paradoxically, but perhaps inevitably, as things are getting better in the wake of the COVID crisis tempers – including, it would seem, that of Scott Morrison – are becoming more frayed.

The Black Lives Matter demonstrations of last weekend marked a new stage in this strange and unpredictable journey coronavirus has taken us on.

The fallout from the murder of an unarmed black man, George Floyd, in the United States dramatically changed the COVID conversation in this country.

The protests exposed limits to the ability of leaders and health experts to persuade people to modify their behaviour.

They unleashed a backlash on the grounds of double standards, with critics contrasting how police had chased minor infringements. Those who’d always claimed the restrictions were too strict became louder in their demands they be lifted more quickly and comprehensively.

The tone of Morrison changed and sharpened, as the government struggles with its exit strategy.

Morrison says if protesters are on the streets in coming days, they should be charged. But the picture is confusing and potentially volatile.

In the Northern Territory, the demonstrators have an official OK. In NSW the police have been actively resisting more protests and are threatening fines and arrests. On Thursday night they succeeded in having the NSW Supreme Court ban a proposed rally organised by refugee advocates.

Read more:

Australia needs to confront its history of white privilege to provide a level playing field for all

On another front, Morrison’s frustration with those premiers who are keeping their borders shut has ramped up.

Having managed the crisis very effectively so far, and received extensive praise for his efforts (this week’s Essential poll had 70% rating the federal government’s response as good), Morrison can see the danger of things going awry, either through fresh outbreaks of the virus or the reopening not proceeding fast enough.

On Thursday he was suggesting the protesters were slowing an increase in the numbers allowed at funerals (a highly emotive issue). Asked on 2GB about the NSW situation on funerals he said “the rally last weekend is the only legitimate real block to this at the moment, because we actually don’t know right now whether those rallies on the weekend may have caused outbreaks”.

But the government is sending conflicting messages, on one hand indicating the protests could hold back action while on the other hand saying action must go ahead.

Thus Morrison is insisting premiers nominate a date in July when their borders would be open (a date is important so tourist arrangements can be made).

Although there are multiple states with closed borders, Queensland is primarily in the sights of the federal government and other critics. Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk, facing an election in October, knows she has to choose the right moment to scrap the border restriction, before her hard line loses favour with her electors. She is now saying July (previously there was talk of later) and declaring she’s on the same page as the PM.

One man who attended the Melbourne rally has tested positive for COVID-19. But it will be more than another week before it becomes clear whether last weekend’s protests have triggered a health problem. And that timeline will be dragged out by protests to come. On the flip side, if there aren’t more cases, this will be a green light to accelerate progress – an unsanctioned large scale trial.

The protests have put new pressures on the opposition.

Knowing there’d be strong support for them among some in Labor’s ranks and base, Anthony Albanese stepped carefully on boggy ground, advising people to listen to the health advice.

Four federal Labor parliamentarians – Graham Perrett and Anika Wells from Queensland, and Warren Snowdon and Malarndirri McCarthy from the Northern Territory – attended rallies. There was a bit of a flurry when they got to parliament so they went for COVID tests (which didn’t mean much given the incubation period).

Despite parliament sitting this week, the opposition is still having a hard time achieving any positive cut-through. It struggles for traction with its attacks on inadequacies it identifies in government’s programs and decisions relating to COVID.

The political climate might change as the months go on; depending on the result, the July 4 Eden-Monaro byelection could affect the atmospherics of the wider debate. But at the moment people still seem turned off by political conflict, or by politics generally.

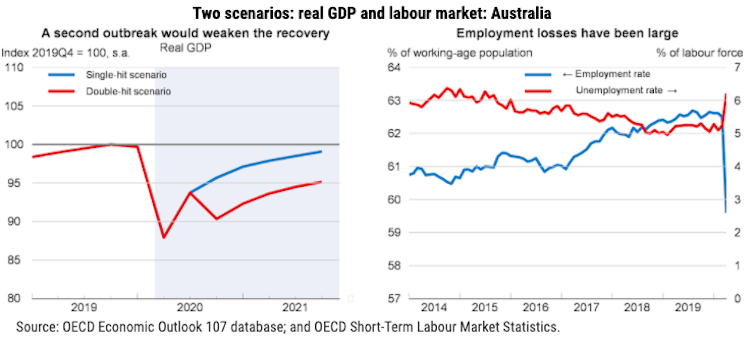

This week brought updated numbers, from the OECD, on Australia’s way out of the virus crisis. The OECD produced two scenarios, for a “single hit” and a “double hit” of the virus.

It estimated Australia’s GDP would fall 5% in 2020 in the single-hit scenario, which is hopefully the one we remain in.

OECD

But the report said: “Should widespread contagion resume, with a return of lockdowns, confidence would suffer and cash-flow would be strained. In that double-hit scenario, GDP could fall by 6.3% in 2020”.

The single hit would see recovery at 4.1% in 2021, but if there were a double hit the growth would be only an estimated 1%.

The OECD also says further policy measures would help the recovery, and notes there is plenty of fiscal room to provide them.

It’s interesting to compare New Zealand, which had a goal of “eliminating” COVID and a draconian lockdown.

The OECD predicts New Zealand GDP will shrink by 8.9% in 2020 under the single-hit scenario – but grow by 6.6% in 2021. If there were a double hit, this year’s GDP fall would be 10% and next year’s growth would be an estimated 3.6%.

New Zealand this week announced it was now COVID-free (while accepting, realistically, there’ll almost certainly be some future cases). Restrictions are now fully lifted, apart from the still-closed border.

The Morrison government from the start rejected “elimination” in favour of suppression (although in some areas elimination has effectively been the result of successful suppression).

Read more:

Voices, hearts and hands – how the powerful sounds of protest have changed over time

So with the shutdown more limited in Australia than in New Zealand but the reopening more gradual, on the OECD figures the economy’s dive is forecast to be shallower here but the bounce back weaker than across the Tasman.

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said she “did a little dance” when her country became COVID-free.

Morrison isn’t dancing just yet. While compared with many countries Australia’s record has been enviable, the way forward carries a new, and unexpected, element of uncertainty, together with those we knew about already.

FRIDAY UPDATE: More COVID restrictions to be eased; Queensland border set to open July 10

The Queensland government has indicated it will open its border from July 10, while South Australia on Friday said its borders will be fully open on July 20, and Tasmania is looking to a late July opening. Western Australia is still not setting a date for an open border.

Friday’s national cabinet, ahead of a new round of demonstrations, reiterated the health advice “that protests are very high risk due to the large numbers of people closely gathering and challenges in identifying all contacts.”

Scott Morrison again strongly urged people to stay away from rallies, and Anthony Albanese endorsed the health advice.

National cabinet agreed to the easing of more restrictions. The 100-person limit on non-essential indoor gatherings will be replaced by one person per four square metres rule.

For outdoor events including stadiums up to 40,000 capacity, ticketed and seated events will be able to be held with a crowd of no more than 25% of the venue’s capacity.

States and territories will decide when to implement these changes.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Protest has helped define the first two decades of the 21st century – here’s what’s next

Feyzi Ismail, SOAS, University of London

The first two decades of the 21st century saw the return of mass movements to streets around the world. Partly a product of sinking confidence in mainstream politics, mass mobilisation has had a huge impact on both official politics and wider society, and protest has become the form of political expression to which millions of people turn.

2019 has ended with protests on a global scale, most notably in Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa, Hong Kong and across India, which has recently flared up against Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Citizenship Amendment Act. In some cases protests are explicitly against neoliberal reforms, or against legal changes that threaten civil liberties. In others they are against inaction over the climate crisis, now driven by a generation of young people new to politics in dozens of countries.

As we end a turbulent two decades of protest – the subject of much of my own teaching and ongoing research – what will be the shape of protest in the 2020s?

Read more:

School climate strikes: what next for the latest generation of activists?

What’s changed in the 21st century

Following moments of open class warfare in the late 1960s and early 1970s, battles against the political and economic order became fragmented, trade unions were attacked, the legacy of the anti-colonial struggles was eroded and the history of the period was recast by the establishment to undermine its potency. In the post-Cold War era, a new phase of protest finally began to overcome these defeats.

This revival of protest exploded onto the political scene most visibly in Seattle outside the World Trade Organization summit in 1999. If 1968 was one of the high points of radical struggle in the 20th century, protest in the early 2000s once again began to reflect a general critique of the capitalist system, with solidarity forged across different sections of society.

Seattle Municipal Archives, CC BY-SA

The birth of the anti-globalisation movement in Seattle was followed by extraordinary mobilisations outside gatherings of the global economic elite. Alternative spaces were also created for the global justice movement to connect, most notably the World Social Forums (WSFs), starting with Porto Alegre, Brazil in 2001. It was here that questions over what position the anti-globalisation movement should take over the Iraq War, for example, were discussed and debated. Though the WSFs provided an important rallying point for a time, they ultimately evaded politics.

The global anti-war movement led to the biggest co-ordinated demonstrations in the history of protest on February 15 2003, in which millions of people demonstrated in over 800 cities, creating a crisis of democracy around the US and UK-led intervention in Iraq.

In the years leading up to and following the banking crisis of 2008, food riots and anti-austerity protests escalated around the world. In parts of the Middle East and North Africa, protests achieved insurrectionary proportions, with the overthrow of one dictator after another. After the Arab Spring was thwarted by counter-revolution, the Occupy movement and then Black Lives Matter gained global attention. While the public, urban square became a central focus for protest, social media became an important – but by no means exclusive – organising tool.

To varying degrees, these movements sharply raised the question of political transformation but didn’t find new ways of institutionalising popular power. The result was that in a number of situations, protest movements fell back on widely distrusted parliamentary processes to try and pursue their political aims. The results of this parliamentary turn have not been impressive.

Crisis of representation

On the one hand, the first two decades of the 21st century have seen soaring inequality, accompanied by debt and the neglect of working people. On the other, there have been poor results from purely parliamentary attempts to challenge it. There is, in other words, a deep crisis of representation.

The inability of modern capitalism to deliver more than survival for many has combined with a general critique of neoliberal capitalism to create a situation in which wider and wider sections of society are being drawn into protest. More than a million people have poured onto the streets of Lebanon since mid-October and protests continue despite a violent crackdown by security forces.

At the same time, people are less and less willing to accept unrepresentative politicians – and this is likely to continue in the future. From Lebanon and Iraq to Chile and Hong Kong, mass mobilisations continue despite resignations and concessions.

In Britain, the Labour Party’s defeat in the recent general election is attributed largely to its failure to accept the 2016 referendum result over EU membership. Decades of loyalty to the Labour Party for many and a socialist leader in Jeremy Corbyn calling for an end to austerity couldn’t cut through to enough of the millions who voted for Brexit.

In France, a general strike in December 2019 over President Emmanuel Macron’s proposed pension reforms has revealed the extent of opposition that people feel towards his government. This comes barely a year after the start of the Yellow Vest movement, in which people have protested against fuel price hikes and the precariousness of their lives.

The tendency towards street protest will be encouraged too by the climate crisis, whose effects mean that the most heavily exploited, including along race and gender lines, have the most to lose. When the protests in Lebanon broke out, they were taking place alongside rampant wildfires.

Thinking strategically

As protesters gain experience, they consciously bring to the fore questions of leadership and organisation. In Lebanon and Iraq there has already been a conscious effort to overcome traditional sectarian divides. Debates are also raging in protest movements from Algeria to Chile about how to fuse economic and political demands in a more strategic manner. The goal is to make political and economic demands inseparable, such that it’s impossible for a government to make political concessions without making economic ones too.

Read more:

The future of protest is high tech – just look at the Catalan independence movement

As the 2020s begin, it’s clear we’re living in an unprecedented moment: a climate emergency and ecological breakdown, a brewing global financial crisis, deepening inequality, trade wars, and growing threats of more imperialist wars and militarisation.

There has also been a resurgence of the far right in many countries, emboldened most visibly by parties and politicians in the US, Brazil, India and many parts of Europe. This resurgence, however, has not gone unchallenged.

The convergence of crisis on these multiple fronts will reach breaking point, creating conditions that will become intolerable for most people. This will galvanise more protest and more polarisation. As governments respond with reforms, such measures on their own will be unlikely to meet the combination of political and economic demands. The question of how to create new vehicles of representation to assert popular control over the economy will keep emerging. The fortunes of popular protest may well depend on whether the collective leadership of the movements can provide answers to it.![]()

Feyzi Ismail, Senior Teaching Fellow, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We live in a world of upheaval. So why aren’t today’s protests leading to revolutions?

Orlando Barria/EPA

Peter McPhee, University of Melbourne

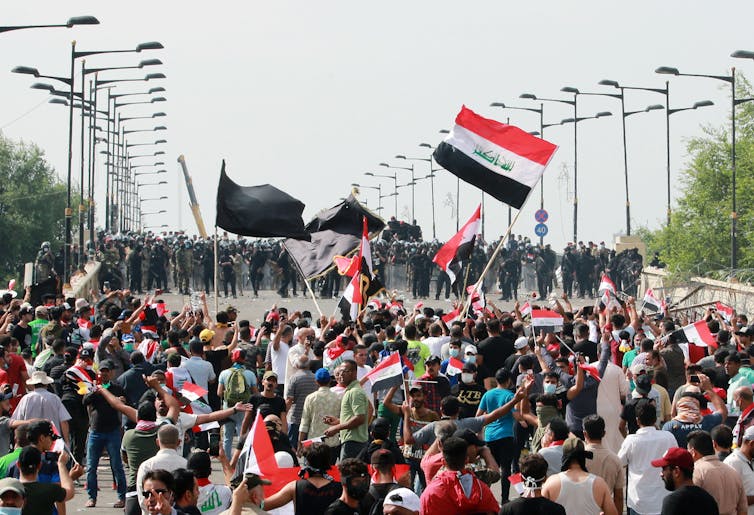

We live in a world of violent challenges to the status quo, from Chile and Iraq to Hong Kong, Catalonia and the Extinction Rebellion. These protests are usually presented in the media simply as expressions of rage at “the system” and are eminently suitable for TV news coverage, where they flash across our screens in 15-second splashes of colour, smoke and sometimes blood.

These are huge rebellions. In Chile, for example, an estimated one million people demonstrated last month. By the next day, 19 people had died, nearly 2,500 had been injured and more than 2,800 arrested.

How might we make sense of these upheavals? Are they revolutionary or just a series of spectacular eruptions of anger? And are they doomed to fail?

Ahmed Jalil/EPA

Key characteristics of a revolution

As an historian of the French Revolution of 1789-99, I often ponder the similarities between the five great revolutions of the modern world – the English Revolution (1649), American Revolution (1776), French Revolution (1789), Russian Revolution (1917) and Chinese Revolution (1949).

A key question today is whether the rebellions we are currently witnessing are also revolutionary.

A model of revolution drawn from the five great revolutions can tell us much about why they occur and take particular trajectories. The key characteristics are:

-

long-term causes and the popularity of a socio-political ideology at odds with the regime in power

-

short-term triggers of widespread protest

-

moments of violent confrontation the power-holders are unable to contain as sections of the armed forces defect to rebels

-

the consolidation of a broad and victorious alliance against the existing regime

-

a subsequent fracturing of the revolutionary alliance as competing factions vie for power

-

the re-establishment of a new order when a revolutionary leader succeeds in consolidating power.

Fazry Ismail/EPA

Why today’s protests are not revolutionary

This model indicates the upheavals in our contemporary world are not revolutionary – or not yet.

The most likely to become revolutionary is in Iraq, where the regime has shown a willingness to kill its own citizens (more than 300 in October alone). This indicates that any concessions to demonstrators will inevitably be regarded as inadequate.

We do not know how the extraordinary rebellion in Hong Kong will end, but it may be very telling there does not seem to have been significant defection from the police or army to the protest movement.

Read more:

Is there hope for a Hong Kong revolution?

People grow angry far more often than they rebel. And rebellions rarely become revolutions.

So, we need to distinguish between major revolutions that transform social and political structures, coups by armed elites and common forms of protest over particular issues. An example of this is the massive, violent and ultimately successful protests in Ecuador last month that forced the government to cancel an austerity package.

Paolo Aguilar/EPA

The protests in Hong Kong and Catalonia fall into yet another category: they have limited aims for political sovereignty rather than more general objectives.

All successful revolutions are characterised by broad alliances at the outset as the deep-seated grievances of a range of social groups coalesce around opposition to the existing regime.

They begin with mass support. For that reason, the Extinction Rebellion will likely only succeed with modest goals of pushing reluctant governments to do more about climate change, rather than its far more ambitious aspirations of

a national Citizen Assembly, populated by ordinary people chosen at random, to come up with a programme for change.

Mass protests also fail when they are unable to create unity around core objectives. The Arab Spring, for instance, held so much promise after blossoming in 2010, but with the possible exception of Tunisia, failed to lead to meaningful change.

Revolutionary alliances collapsed rapidly into civil war (as in Libya) or failed to neutralise the armed forces (as in Egypt and Syria).

Why is there so much anger?

Fundamental to an understanding of the rage so evident today is the “democratic deficit”. This refers to public anger at the way the high-water mark of democratic reform around the globe in the 1990s – accompanied by the siren song of economic globalisation – has had such uneven social outcomes.

One expression of this anger has been the rise of fearful xenophobia expertly captured by populist politicians, most famously in the case of Donald Trump, but including many others from Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil to Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Victor Orbán in Hungary.

Read more:

The Joker to Guy Fawkes: why protesters around the world are wearing the same masks

Indeed, there are some who claim that western liberalism has now failed).

Elsewhere, the anger is popular rather than populist. In upheavals from Lebanon and Iraq to Zimbabwe and Chile, resentment is particularly focused on the evidence of widespread corruption as elites flout the basic norms of transparency and equity in siphoning government money into their pockets and those of their cronies.

Wael Hamzeh/EPA

The broader context of today’s upheavals also includes the uneven withdrawal of the US from international engagement, providing new opportunities for two authoritarian superpowers (Russia and China) driven by dreams of new empires.

The United Nations, meanwhile, is floundering in its attempt to provide alternative leadership through a rules-based international system.

The state of the world economy also plays a role. In places where economic growth is stagnant, minor price increases are more than just irritants. They explode into rebellions, such as the recent tax on WhatsApp in Lebanon and the metro fare rise in Chile.

There was already deep-seated anger in both places. Chile, for example, is one of Latin America’s wealthiest countries, but has one of the worst levels of income equality among the 36 nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rebellions with new characteristics

Of course, we do not know how these protest movements will end. While it is unlikely any of the rebellions will result in revolutionary change, we are witnessing distinctly 21st century upheavals with new characteristics.

One of the most influential approaches to understanding the long-term history and nature of protest and insurrection has come from the American sociologist Charles Tilly.

Read more:

Animal rights activists in Melbourne: green-collar criminals or civil ‘disobedients’?

Tilly’s studies of European history have identified two key characteristics.

First, forms of protest change across time as a function of wider changes in economic and political structures. The food riots of pre-industrial society, for instance, gave way to the strikes and political demonstrations of the modern world.

And today, the transnational reach of Extinction Rebellion is symptomatic of a new global age. There are also new protest tactics emerging, such as the flashmobs and Lennon walls in Hong Kong.

Bianca de Marchi/AAP

Tilly’s second theory was that collective protest, both peaceful and violent, is endemic rather than confined to years of spectacular revolutionary upheaval, such as 1789 or 1917. It is a continuing expression of conflict between “contenders” for power, including the state. It is part of the historical fabric of all societies.

Even in a stable and prosperous country like Australia in 2019, there is a deep cynicism around a commitment to the common good. This has been created by a lack of clear leadership on climate change and energy policy, self-serving corporate governance and fortress politics.

All this suggests that Prime Minister Scott Morrison is not only whistling in the wind if he thinks that he can dictate the nature of and even reduce protest in contemporary Australia – he is also ignorant of its history.![]()

Peter McPhee, Emeritus professor, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.