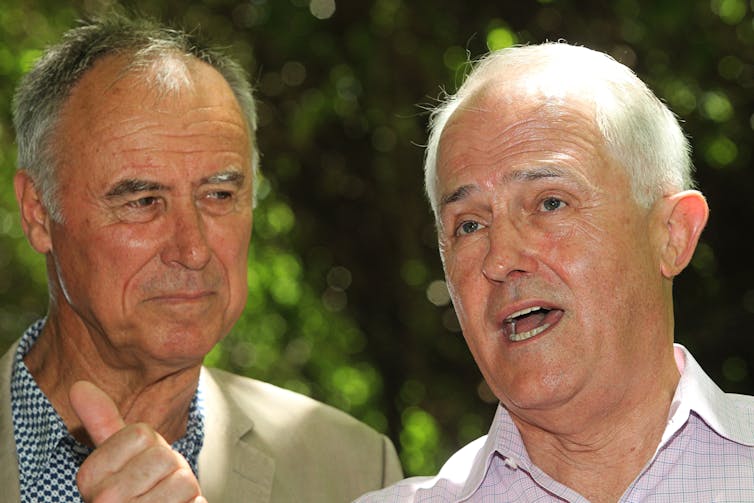

AAP/Richard Wainwright

Adrian Beaumont, The University of Melbourne

With 43% of enrolled voters counted in yesterday’s Western Australian election, the ABC was calling Labor wins in 49 of the 59 lower house seats, to just two for the Liberals and three for the Nationals. Five seats remained in doubt.

The current final outcome prediction is 52 Labor, three Liberals and four Nationals. Since the 2017 election, this would be an 11-seat gain for Labor and a 10-seat loss for the Liberals. Liberal casualties included current leader Zak Kirkup’s seat of Dawesville, and former leader Liza Harvey’s Scarborough.

Statewide primary vote shares were a massive 59.1% for Labor (up 16.9% since 2017), 21.3% Liberals (down 9.9%), 4.5% National (down 0.9%), 7.1% Greens (down 1.8%) and just 1.3% for One Nation (down 3.7%). The Poll Bludger’s statewide two party projection is 69.2-30.8 to Labor, a 13.7% swing to Labor.

With 30.8% of the upper house vote counted, the ABC’s group ticket voting calculators are giving Labor 22 of the 36 seats (up eight), the Liberals six (down three), the Nationals four (steady), Legalise Cannabis two (up two), the Shooters and Fishers one (steady) and the Greens one (down three).

Current results show Labor winning 20 of its 22 seats on raw quotas without requiring preferences. They need a small amount of preferences to win three seats in Agricultural region and four in North Metropolitan. Labor is set to win the heavily malapportioned upper house for the first time in its history.

Read more:

Whopping lead for Labor ahead of WA election, but federal Newspoll deadlocked at 50-50

Why this result occurred

As I wrote recently, the current 69-31 two party result is probably the most lopsided ever in Australian electoral history for any state or federally. Labor’s primary vote may drop back as more votes are counted, but will be at least roughly level with the combined National and Liberal vote at the Queensland 1974 election.

With the opposite party in power federally, and campaigning for its second term, Labor was likely to win unless they had major stuff-ups. But Premier Mark McGowan’s handling of COVID created this record landslide.

Imposing hard borders to stop the spread was very popular, and with relatively few cases in WA, life remained relatively normal with the exception of a five-day lockdown in early February. In the final pre-election Newspoll, McGowan’s ratings were 88% satisfied and just 10% dissatisfied.

I do not think there are federal implications from this massive Labor victory at the state level. While not at McGowan’s levels, Scott Morrison was still very popular by historical standards at 64% satisfied, 32% dissatisfied in the last federal Newspoll.

If being perceived as dealing well with COVID is a criterion for a successful re-election, the federal Coalition would be likely to win now.

In February 2001, Peter Beattie led Queensland Labor to 66 of the 89 lower house seats, to just 15 for the Coalition parties. But in November 2001, the federal Coalition under John Howard was re-elected, with the Coalition winning 19 of the 27 federal Queeensland seats.

Many people did not believe the 68-32 Newspoll three weeks ago, and the final pre-election Newspoll (66-34) was also hard to believe. But Labor has exceeded both these Newspolls. A YouGov poll of Dawesville had Labor winning by 60-40; it’s currently 64.5-35.5. Expecting outcomes to be narrower than polls indicate can be a big mistake.

Biden’s $US 1.9 trillion stimulus becomes law

To revive the US economy from its COVID-induced recession, President Joe Biden proposed a $US 1.9 trillion stimulus. On March 6, this stimulus passed the US Senate on a 50-49 vote, with all 50 Democrats in support and all Republicans opposed; one Republican missed the vote.

Had the vote been tied at 50-50, Vice President Kamala Harris would have broken the tie. This stimulus vote shows how important the two narrow Democratic wins in the January 5 Georgia Senate runoffs were.

Without those victories, there is no possibility this stimulus would have become law, and Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell would still control the Senate’s agenda, enabling him to deny votes on items he disliked.

On Wednesday the House of Representatives, which had earlier passed its own version of the stimulus, agreed to the Senate’s amendments by a 220-211 margin. Biden signed the stimulus into law on Thursday. All Republicans who voted in either chamber of Congress opposed the stimulus.![]()

Adrian Beaumont, Honorary Associate, School of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.