Sharon Bessell, Australian National UniversityAs the pandemic swept the globe in 2020, Australia stood out as a model for how to contain the virus and support its citizens.

A year later, Australia is struggling with vaccination and has abandoned the measures it put in place in 2020 to support the most vulnerable.

The A$750 per week COVID disaster payment to Australians in jobs is as big as the biggest of last year’s JobKeeper payments. It has been extended to the casual workers employed for less than a year and visa holders who missed out last time.

And it’s being delivered direct to the recipients rather than via employers, some of whom appeared to have pocketed the money last time. So far, so good.

For the newly unemployed and people on parenting payments there’s an extra $200 per week — but only if they’ve lost more than eight hours’ per week work.

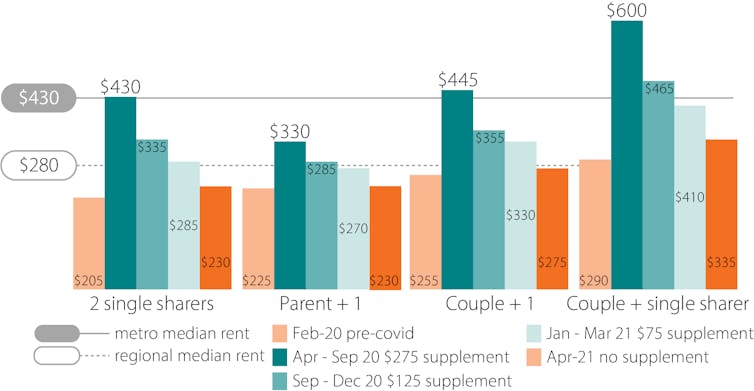

What’s missing is last year’s effective doubling of JobSeeker and related benefits for people who were already out of work: the $550 per fortnight add-on that lifted the payment up towards the poverty line.

An estimated 540,000 of the 720,000 adults locked down on such payments don’t get the $200 per week because they didn’t have paid work ahead of the lockdown.

They are unable to find it during the lockdown and have to live on $44 a day — well below the poverty line.

The COVID supplement changed lives

Last year the so-called coronavirus supplement made all the difference, allowing those families to buy essential items including food and medical care that were previously out of reach.

An online survey conducted by Swinburne University and the Australian National University found the money was used for basic needs and strategic expenditures to “improve their household’s long-term financial security”.

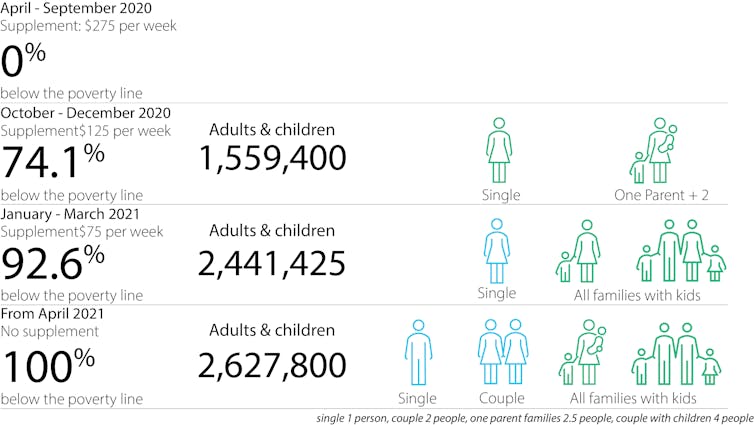

The Australian National University found poverty rates dropped markedly for couples with children, and even more for single parent households.

Before COVID hit, the poverty rate in single parent households was 20.2%. In the absence of policy change and the advent of COVID-19 it would have climbed to 27.9%. The COVID stimulus payments cut it to just 7.6% in June.

A survey of single mothers found 88% suffered less anxiety. More than two-thirds (69%) reported being healthier as a result of being able to buy enough and healthier food.

So valued was the $550 per fortnight it sparked a website, 550 Reasons to Smile, showcasing stories of the changes it had wrought.

An old gas heater died and thankfully to the $550 supplement I was able to go and purchase a new one straight away to keep my new baby and 2 other children warm at night (one has severe croup)

We could afford a new phone. We are both in our early 60s and our best skill was hiding our poverty after our small business, our life, went bankrupt. We would skip meals before the grandchildren would visit to afford those treats.

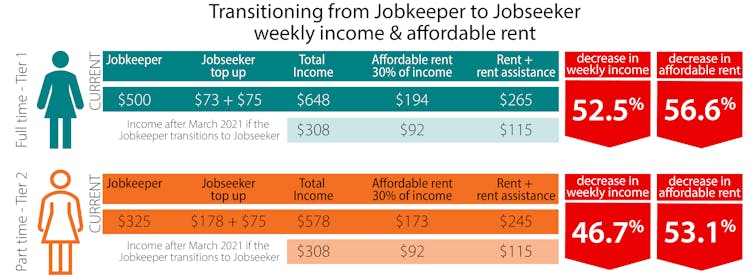

When the $150 per fortnight that remained of the coronavirus supplement after it had been phased down ended on March 28 this year, it was replaced by a permanent increase in JobSeeker and similar benefits of only $50 per fortnight.

It plunged hundreds of thousands of children back into poverty.

Toys and food matter to children

Prior to COVID-19, I led a research project with children aged between seven and 12. Two-thirds lived in locations identified by standard indicators as disadvantaged.

We gave children the time to raise issues that mattered to them. There was discussion about favourite and longed-for toys, games, and devices; the most fun parks and playgrounds; and the ups and downs of friendships.

Yuganov Konstantin/Shutterstock

As the research unfolded and children felt more comfortable, they raised the challenges of not having enough money to meet the most basic needs.

Some had only one meal a day and not all were offered school breakfasts.

A nine-year-old boy described his neighbours as “good” and “always helpful”. He said they provided food when his family could not afford to buy it.

A common theme was the imperative to protect their parents by not asking for things they needed, including things for school.

This is the reality of poverty — a reality to which too many Australian children are currently being abandoned.![]()

Sharon Bessell, Professor of Public Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.