Geoff Hanmer and Bruce Milthorpe, University of Technology Sydney

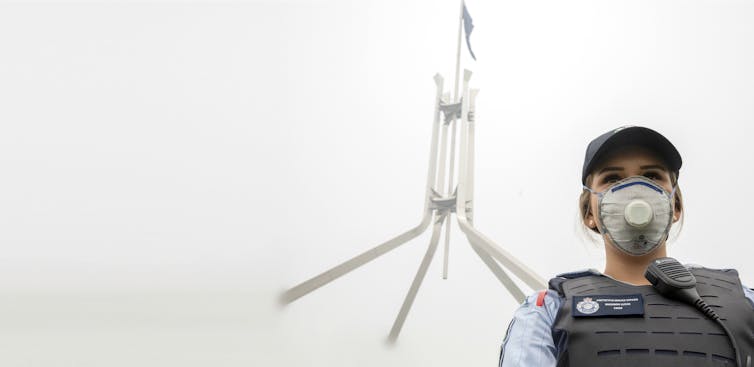

The virus that causes COVID-19 is much more likely to spread indoors rather than outdoors. Governments are right to encourage more outdoor dining and drinking, but it is important they also do everything they can to make indoor venues as safe as possible. Our recent monitoring of public buildings has shown many have poor ventilation.

Poor ventilation raises the risks of super-spreader events. The risk of catching COVID-19 indoors is 18.7 times higher than in the open air, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read more:

Poor ventilation may be adding to nursing homes’ COVID-19 risks

In the past month, we have measured air quality in a large number of public buildings. High carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels indicate poor ventilation. Multiple restaurants, two hotels, two major shopping centres, several university buildings, a pharmacy and a GP consulting suite had CO₂ levels well above best practice and also above the absolute maximum mandated in the National Construction Code.

Relative humidity readings of less than 40% associated with both heating and cooling air are also of concern. Evidence now suggests low humidity is associated with transmission.

If anyone had COVID-19 in these environments, particularly if people were in them for an extended period, as might happen at a restaurant or pub, there would be a risk of a super-spreader event. Less than 20% of individuals produce over 80% of infections.

Read more:

A few superspreaders transmit the majority of coronavirus cases

Many aged-care deaths were connected

It appears a relatively small number of super-spreader events, probably associated with airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, were responsible for most of the deaths in Victorian aged-care facilities.

Of the 907 people who have died of COVID-19 in Australia, 746, or 82% of COVID-19 deaths, were associated with aged care. In Victoria, there were 52 facilities with more than 20 infections. Three had over 200 infections. As a result, 639 of the 646 aged care residents who died in Victoria were located in just 52 facilities.

But official advice hasn’t changed

Aged-care operators and the states based their infection control on the advice of the Commonwealth Infection Control Expert Group (ICEG). As of September 6, the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Residential Aged Care Facilities Plan for Victoria stated:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) is transmitted via droplets, after exposure to contaminated surfaces or after close contact with an infected person (without using appropriate PPE). Airborne spread has not been reported [our emphasis] but could occur during certain aerosol-generating procedures (medical procedures which are not usually conducted in RACF). […] Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette, hand hygiene and regular cleaning of surfaces are paramount to preventing transmission.

In early August, more than 3,000 health workers had signed a letter of no confidence in ICEG. The letter noted that aerosol transmission was causing infections in medical staff, many of whom worked in aged-care facilities.

On September 7, we wrote to the federal aged care minister, Richard Colbeck, drawing attention to our August 20 article in The Conversation, which referenced a July 8 article in Nature. The Nature article identified an emerging consensus that aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is probable in low-ventilation environments.

Read more:

How to prevent COVID-19 ‘superspreader’ events indoors this winter

The director of the Aged Care COVID-19 Measures Implementation Branch wrote back on Colbeck’s behalf on September 28 saying:

Current evidence suggests COVID-19 most commonly spreads from close contact with someone who is infectious. It can also spread from touching a surface that has recently been contaminated with the respiratory droplets (cough or sneeze) of an infected person and then touching your eyes, nose or mouth.

In other words, Commonwealth authorities were still playing down the significance of airborne transmission nearly two months after the letter of no confidence was sent to ICEG and three months after the article in Nature. By the end of September, Victorian aged-care facilities had reported over 4,000 cases of COVID-19, about half of them in staff.

On October 23, ICEG was still saying:

There is little clinical or epidemiological evidence of significant transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) by aerosols.

Focus on the ‘3 Vs’ to reduce risks

The key thing we need to do until a vaccine is rolled out is to try to prevent indoor super-spreader events. According to the University of Nebraska Medical Centre, we should remember the “three Vs” that super-spreader events have in common:

Venue: multiple people indoors, where social distancing is often harder

Ventilation: staying in one place with limited fresh air

Vocalization: lots of talking, yelling or singing, which can aerosolize the virus.

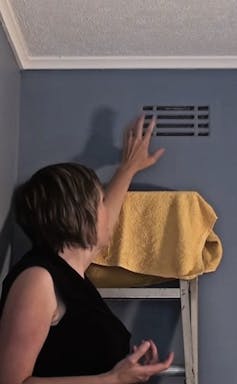

Measuring indoor ventilation is quick and easy using a carbon dioxide detector. Any CO₂ reading of over 800 parts per million is a cause for concern – the level for air outside is just over 400ppm.

There is no excuse for governments, health authorities and building owners not to monitor ventilation levels to help ensure members of the public are as safe as is reasonably practicable when indoors.

There is also no excuse for the Australian Building Control Board not to change the National Construction Code to require fall-back mechanical ventilation systems be fitted and CO₂ and humidity monitored in all buildings frequented by the public, particularly aged-care facilities.

With the knowledge we have now and a low rate of community infection, Australia should be able to make it through to vaccine roll-out with relatively few further infections and deaths. But that depends on being vigilant about the quality of ventilation indoors and the associated possibility of super-spreader events. This is especially important in aged-care facilities and quarantine hotels.

It’s probably a good idea for us all to open the windows and let the fresh air in.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture and Bruce Milthorpe, Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.