Michael Duffy, Monash University

The revelations in the “palace letters” may well renew enthusiasm for an Australian republic, especially coming on top of recent controversies involving both older and younger members of the royal family.

A recent poll also suggests increasing popular support for a republic. According to the YouGov poll, 62% of Australians said they wanted the head of state to be an Australian.

The palace letters make clear the problem with our current set-up: we have a legal (what lawyers call de jure) head of state who is a resident and national of the UK (the queen), as well as an effective or de facto Australian head of state (the governor-general) who can operate as if that legal status was his/hers.

Read more:

First reconciliation, then a republic – starting with changing the date of Australia Day

Aside from the symbolism of having a foreign head of state – a blow to nativist Australian pride – there is also the practical question of whether the legal status and system of appointment (and removal) of the Australian governor-general is the best we can do.

This challenge is highlighted by the palace letters. They illustrate quite clearly that in extreme situations, such as when Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was dismissed by the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, in 1975, this arrangement can invite what has been referred to as a game of “constitutional chicken”.

This occurs when a governor-general is in fear of being dismissed by the queen (on the advice of the Australian prime minister), while the prime minister can simultaneously be in fear of being dismissed by the governor-general. This situation gives each an incentive to act first to dismiss the other.

What happened in the 1999 referendum

The republican model put to voters in a referendum in 1999 didn’t really fix that problem, as it still gave the prime minister the direct power to remove the head of state.

The other problem with the 1999 “minimalist” republic model was that it was attacked by some republicans who wanted a popular vote to select the head of state.

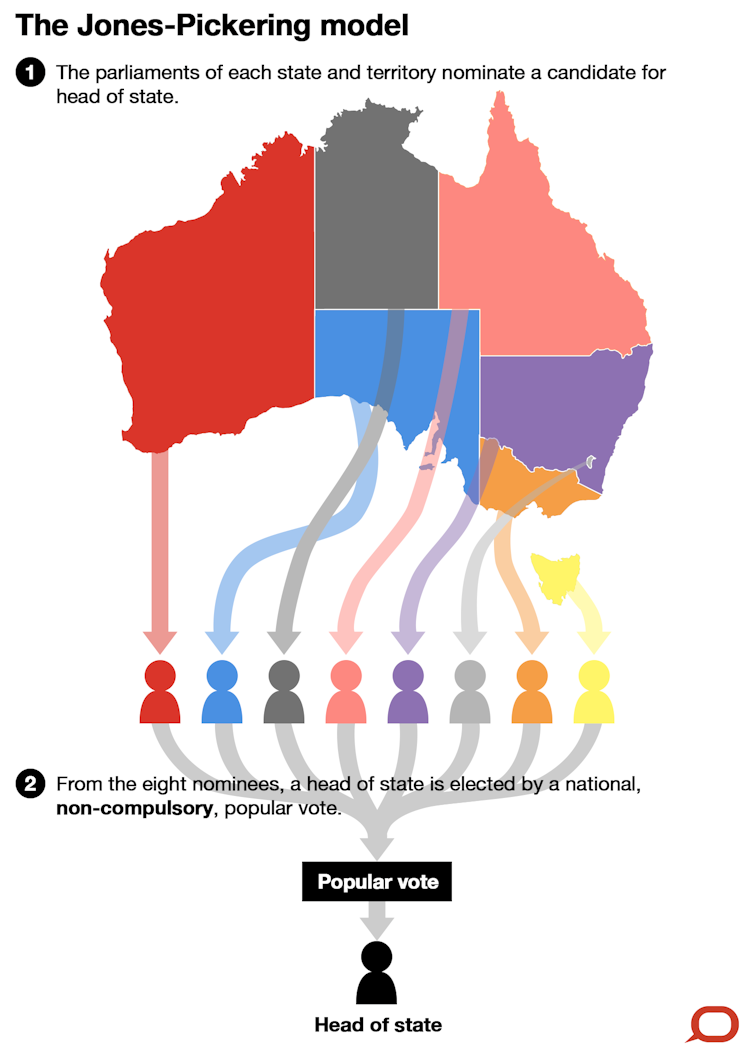

There has been disagreement since then between minimalist republicans, who favour parliamentary appointment of a ceremonial head of state (such as in India and Israel), and “direct electionists”, who want a direct vote for the head of state by the people (like Ireland and Austria).

Read more:

A model for an Australian republic that can unite republicans and win a referendum

In the 1999 referendum, some direct electionists opposed the minimalist republic model and effectively joined with monarchists in defeating the proposal.

The challenge for the republican cause now is that many minimalist republicans may well vote against a direct election model in another referendum.

For them, the fear is Australia would move away from the Westminster system towards a US-style presidential system. And Donald Trump’s rise to power in the US, in particular, has led some to question the potential for popular votes to produce demagogues.

How republic models could work

So, what would it take for another republican referendum to succeed in Australia?

For starters, there must be a model that somehow unites the republican cause by allowing for a popular election but retaining a ceremonial, non-executive head of state. This head of state, apart from reserve powers, essentially defers to the parliament and prime minister.

In other words, such a model must preserve responsible government – a government that comes from, and is responsible to, the parliament.

Some “hybrid” republic models have been proposed, and my colleagues and I added our own ideas to the debate in a paper published in the Public Law Review in 2018.

In 2001, the late constitutional law professor George Winterton proposed an alternative bipartisan choice idea. In this model, parliament would endorse one candidate for head of state who would then be voted on in a popular national election (in which limited other nominees were free to stand).

We endorse this, but suggest that for such a model to work, provisions may be needed to bind the major political parties to the candidate selected by parliament. This would prevent parties or factions from campaigning for their own rival candidates.

Read more:

Cabinet papers 1994-95: How the republic was doomed without a directly elected president

Another proposal is the “50-50” model, which aggregates the results of a parliamentary and popular vote, giving equal weight to both. This concept seeks to unite minimalists and direct electionists by requiring some sensible compromise from each side.

To avoid a repeat of Kerr’s dismissal of Gough in 1975, Australia could choose a republic model that includes “concurrent expiration”.

In this model, if a head of state acted to dismiss a sitting prime minister, he or she would also face an early expiration of their own term. Voters would then decide the fates of both in the ensuing election.

Certainly, if there is to be change to a republic in Australia that maintains the Westminster system of responsible government, this will take time, considered thought and debate.

In the very long term, an Australian head of state may be inevitable, so it is important to get it right.![]()

Michael Duffy, Senior Lecturer and Researcher, Monash Business School, Director Corporate Law, Organisation and Litigation Research Group (CLOL), Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.