Alexei Druzhinin/AP

Alexey D Muraviev, Curtin UniversityThe global opinions on the new AUKUS security pact between Australia, the US and the UK have been decidedly mixed. China and France immediately blasted the deal, while others, such as Japan and the Philippines, were more welcoming.

Russia, one of the other few nations armed with nuclear-powered submarines, was more low-key and cautious in its initial reaction.

The Kremlin limited its official commentary to a carefully crafted statement that said,

Before forming a position, we must understand the goals, objectives, means. These questions need to be answered first. There is little information so far.

Some Russian diplomatic officials joined their Chinese counterparts in expressing their concerns that Australia’s development of nuclear-powered submarines (with American and British help) would undermine the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and “speed up an arms race” in the region.

They suggested the construction of the nuclear submarine fleet would need to be overseen by the International Atomic Energy Agency — a proposition unlikely to be acceptable to Canberra.

Read more:

Why nuclear submarines are a smart military move for Australia — and could deter China further

‘Prototype of an Asian NATO’

As more became known about the new security pact, the rhetoric of Kremlin officials began to shift.

For instance, former Australian ambassador to the US, Joe Hockey, boldly declared AUKUS was intended to counter not only China’s power in the Indo-Pacific region, but Russia’s, too.

Soon after, the secretary of Russia’s Security Council, Nikolai Patrushev, was calling the pact a “prototype of an Asian NATO”. He added,

Washington will try to involve other countries in this organisation, chiefly in order to pursue anti-China and anti-Russia policies

This change of rhetoric should not come as a surprise to Canberra. Russia has long considered any change to regional security — the creation of new alliances, for instance, or the deployment of new weapons systems — a military risk that would require a response.

Marketing its own nuclear submarines

So, what possible options could Russia entertain as part of its response?

Since Moscow’s view of AUKUS is more of a political and military risk, but not yet a threat, its immediate responses are likely to be limited to political manoeuvring and opportunity grabbing.

Read more:

Russia not so much a (re)rising superpower as a skilled strategic spoiler

Perhaps most notably, Russia may see the AUKUS submarine deal as setting a precedent, allowing it to promote its own nuclear-submarine technology to interested parties in the region. This is not merely hypothetical — it has been suggested by defence experts with close links to Russia’s Ministry of Defence.

Historically, Russia has held back from sharing its nuclear submarine technology, which is considered among the best in the world, certainly superior to China’s nascent capabilities.

Thus far, Moscow has only entered into leasing arrangements with India, allowing its navy to operate Soviet- and Russian-made nuclear-powered attack submarines since 1987. But this has not entailed the transfer of technology to India.

Should Russia decide to market its nuclear-powered submarines to other nations, it would have no shortage of interested buyers. As one military expert suggested, Vietnam or Algeria are potential markets — but there could be others. As he put it,

Literally before our eyes, a new market for nuclear powered submarines is being created. […] Now we can safely offer a number of our strategic partners.

Expanding its submarine force in the Pacific

In the longer run, Russia will also not disregard the obvious: the new pact unites two nuclear-armed nations (the US and UK) and a soon-to-be-nuclear-capable Australia.

The expanded endurance and range of Australia’s future submarines could see them operating in the western and northwestern Pacific, areas of regular activity for Russia’s naval force.

Bullit Marquez/AP

Should the strike systems on board these submarines have the Russian far east or parts of Siberia within their range, it would be a game-changer for Moscow.

As a nuclear superpower, Russia will need to factor this into its strategic planning. And this means Australia must keep a close watch on Russia’s military activities in the Pacific in the coming years.

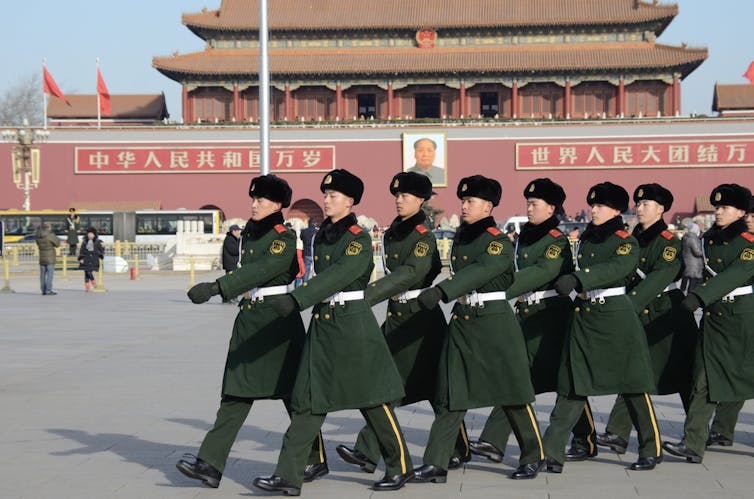

Over the next 12 months, for instance, the Russian Pacific Fleet is expected to receive at least three nuclear-powered submarines.

Two of these fourth-generation submarines (the Yasen-M class) are technologically superior to similar vessels currently being built by the Chinese and are believed to be almost comparable to the American nuclear submarines being considered an option for Australia.

The third is a 30,000-tonne, modified Oscar II class Belgorod submarine converted to carry several nuclear super-torpedos capable of destroying major naval bases.

By 2028, I estimate Russia’s navy will have a force of at least 14 nuclear-powered submarines and six conventional attack submarines in the Pacific.

Should Russia start considering AUKUS a military threat, we could expect more to arrive. Their area of operations could also be expanded to the South China Sea, and beyond.

Deepening naval ties with China

In the most dramatic scenario, Russia and China could form a loose maritime coalition to counter the combined military power of the AUKUS pact.

Given the deepening state of Russia-China defence relations, particularly in the naval sphere, this does not seem unrealistic.

Read more:

Australia’s strategic blind spot: China’s newfound intimacy with once-rival Russia

This possible coalition is unlikely to become an actual maritime alliance, let alone the basis for larger bloc involving other countries. Still, if Russia and China were to coordinate their naval activities, that would be bad news for the AUKUS.

Should tensions escalate, Moscow and Beijing could see Australia as the weakest link of the pact. In its typical bombastic language, China’s Global Times newspaper has already referred to Australia as a “potential target for a nuclear strike”.

This might be a far-fetched scenario, but by entering the nuclear submarine race in the Indo-Pacific, Australia would become part of an elite club, some of whom would be adversaries. And there is the potential for this to lead to a naval Cold War of sorts in the Indo-Pacific.

Sceptics may say Moscow is likely to be all talk but no action and the risks posed by Russia to Australia are minimal. Let’s hope this is correct.![]()

Alexey D Muraviev, Associate Professor of National Security and Strategic Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.