Alexey Druzhinin/SPUTNIK/AFP via Getty Images)

Regina Smyth, Indiana University

When Russians voted in early July on 200 constitutional amendments, officials rigged the election to create the illusion that President Vladimir Putin remains a popular and powerful leader after 20 years in office.

In reality, he increasingly relies on manipulation and state repression to maintain his presidency. Most Russians know that, and the world is catching up.

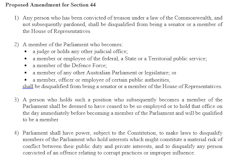

At the center of the changes were new rules to allow Putin to evade term limits and serve two additional terms, extending his tenure until 2036. According to official results, Putin’s regime secured an astounding victory, winning 78% support for the constitutional reform, with 64% turnout. The Kremlin hailed the national vote as confirmation of popular trust in Putin.

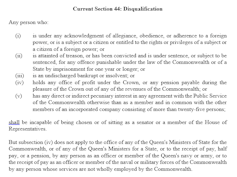

The vote was purely symbolic. The law governing constitutional change does not require a popular vote. By March 2020, the national legislature, Constitutional Court and Russia’s 85 regional legislatures had voted to enact the proposed amendments.

Yet, the president insisted on a show of popular support and national unity to endorse the legal process.

The Kremlin’s goal was to make Putin’s 2024 reelection appear inevitable. Given the stakes, the outcome was never in doubt – but it did little to resolve uncertainty over Russia’s future.

Declining social support

Why hold a vote if a vote isn’t needed?

As a scholar of Russian electoral competition, I see the constitutional vote as a first step in an effort to prolong Putin’s 20-year tenure as the national leader. The Kremlin’s success defined the legal path to reelection and the strategy for securing an electoral majority in the face of popular opposition.

Sefa Karacan/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Its effect on societal attitudes is less clear. A recent poll by the independent polling organization the Levada Center showed that while 52% of respondents supported Putin’s reelection, 44% opposed. At the same time, 59% want to introduce a 70-year-old age cap for presidential candidates. This change would bar the 68-year-old president from running again.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The government’s disorganized and weak response to COVID-19 highlighted the inefficient and corrupt system and produced an unprecedented drop in Putin’s public approval ratings.

Growing signs of popular discontent in Russia suggest this polling data underestimates demand for change. Local protest against pollution, trash incineration and state reforms continue to grow across the Federation. Focus group data reveals that ordinary Russians are concerned about state repression and civil rights violations.

In the leadup to the constitutional vote, internet influencers read the public mood and refused payments for their endorsement, fearing a backlash from followers and advertisers.

A new Putin majority

Declining popular support highlights the difficulty of building a new voting coalition. Manufacturing a demonstration of national unity was the first step in reinventing Putin’s links to core supporters in the runup to the next national election cycle.

By 2012, Putin’s first coalition, forged in the economic recovery of the early 2000s, was eroded by chronic economic stagnation punctuated by crisis.

In the mid-2010s, Putin’s new majority was based on aggressive foreign policy actions. That coalition declined, as conflicts in Ukraine and Syria dragged on, and public support for expensive foreign policy adventures decreased.

The constitutional vote marks Putin’s third attempt to reconstruct electoral support rooted in patriotism, conservative values and state paternalism that echoes the Soviet era.

Fixing the vote

The constitutional reform campaign focused on state benefits rather than the Putin presidency.

Putin offered something for everyone in the 200 amendments.

As an antidote to unpopular pension reforms, a new provision guarantees pensioners annual adjustments linked to inflation. Other amendments codified existing policies guaranteeing housing and a minimum wage. New clauses codify Putin’s version of conservative values, with measures that add a reference to God, a prohibition against same-sex marriage and support for patriotic education. Other provisions take aim at corruption, by prohibiting state officials from holding offshore accounts.

A massive PR campaign framed starkly different appeals to different voter groups. For those concerned with international security, ads depicted apocalyptic visions of Russia’s future after a NATO invasion. For younger voters, appeals depicted happy families voting to support a bright future.

State television featured supportive cultural icons and artists, including Patriarch Kirill, who is the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. Putin himself argued that participation was a patriotic duty. No one mentioned the controversial loophole that would allow Putin to run again.

The campaign foretold the outcome: The regime would stop at nothing to secure success. Officials coerced employees of government agencies and large businesses to turn out. Voters were offered prizes, food and chances to win new housing and cash for participating.

Ostensibly in response to COVID-19, the Electoral Commission altered voting procedures to evade observation, developing a flawed online voting system and creating mobile polling stations in parks, airports and outside apartment blocks. There is overwhelming evidence that the Kremlin resorted to falsification to produce the desired outcome.

Most Russians understand that the manufactured outcome does not accurately reflect attitudes about Putin’s reelection.

Limits of disinformation

There is growing evidence that the public is no longer persuaded by disinformation and political theater such as the rigged constitutional vote. Trust in state media, the president and the government are declining precipitously.

Alexander Nemenov/AFP via Getty Images

The realities of sustained economic stagnation and the Kremlin’s anemic response to COVID-19 stand in sharp contrast to its all-out approach to the symbolic national vote. It can rig a vote, but it can’t control a virus.

The Kremlin’s pandemic response raises doubts about its ability to fulfill new constitutional mandates. Widely publicized efforts to reform the Soviet-era health care system still left hospitals unprepared to manage the pandemic. The state proved incapable of delivering bonuses to first responders and medical workers. The Kremlin refused to use its substantial emergency fund to support entrepreneurs, families with children and the unemployed.

Given these realities, upcoming elections will test the illusion of a new pro-Putin majority defined by this rigged vote. And if the voters abandon Putin, the new Constitution provides a final path to remain in office: the unelected chairmanship of the powerful new State Council.![]()

Regina Smyth, Professor, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.