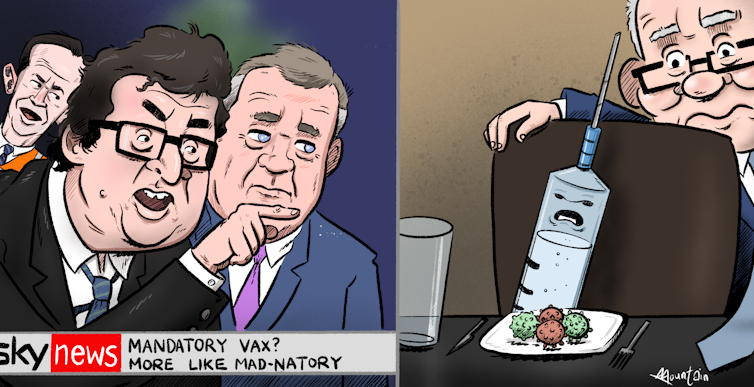

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Frank Bongiorno, Australian National UniversityGreat crises are a stimulus to right-wing political mobilisation. Famously, the Great Depression of the 1930s gave the Nazis their chance. It was a good time for fascists or near-fascists in other countries as well, including Australia. Here, the ground was thick with the Old Guard, New Guard, White Army, Country Movement, New Staters, Western Australian secessionists, patriotic bodies and citizens’ leagues, all claiming to be sick of politics and above it all.

The present pandemic has been no exception. The uncertainty of the times has been a great generator of conspiracy theories and, dangerously, of do-it-yourself medical science. The Depression gave a great boost to funny money theories such as Social Credit, which identified an evil and conspiratorial “money power” as the root of all social and economic evil, a theory that sometimes had anti-Semitic content.

Such conspiracy theories are still with us, expressed most obviously by the obsession of a section of the right with the supposedly malign influence of billionaire George Soros. Others worry Bill Gates is listening in, 5G technology is enslaving us, and vaccination is a plot to destroy our liberty. For many years now, the far right has been preoccupied with Islam. Without abandoning old enemies, it’s now finding new ones to worry about.

But not entirely new. It is a feature of right-wing political mobilisation that it tends to stitch together bits and pieces of fabric that have often been around for a long while, tailoring them into new garments for the present. Anti-vaccination arguments have been around for years. They are now being repurposed for the times.

Where are they coming from? Not entirely from the right, of course: there are wellness and natural lifestyle advocates, and social media influencers, who object to vaccination. Lockdown protesters might be predominantly of the right, but not exclusively so. There is a palpable frustration with restrictions on personal freedom. This extends well beyond those who might consider themselves on the right.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

Still, is it striking that much that is recognisable as right-wing protest about “freedom” at present has its origins in the mainstream politics of the right. Craig Kelly, an enthusiastic purveyor of COVID misinformation, was until recently a Liberal member for a Sydney seat, his preselection under the protection of the current prime minister. John Ruddick, a prominent member of the libertarian Liberal Democrats conspicuous in recent anti-lockdown protests in Sydney, is a former candidate for president of the Liberal Party. Campbell Newman was Liberal National Party premier of Queensland for a term: he’s now also hitched a ride with the Liberal Democrats and announced his Senate candidature in the noble cause of “freedom”. Others complaining of lockdowns and restrictions, such as George Christensen and Matt Canavan, both Queensland federal politicians, remain in the Coalition government.

Read more:

View from The Hill: Barnaby Joyce repudiates Christensen’s COVID misinformation

All of this conforms to a historical pattern. Pauline Hanson would likely never have been heard of if not for Liberal Party preselection for Oxley in 1996. Sky News is fronted by former Liberal advisers such as Alan Jones and Peta Credlin – even if Andrew Bolt once worked on the Labor side of politics and Mark Latham puts in the odd appearance.

The right benefits from our media ecology. The role of the Murdoch media in turning last night’s exotic and extreme into this evening’s political meat and three veg is well enough understood. So is the role of social media in enabling the spread of conspiracy theories, loopy ideas and even violent extremism of the kind witnessed in Washington DC on January 6.

But there is an understandable reluctance on the part of the mainstream media, given their complicity, in exploring their own role in facilitating right-wing political mobilisation. Just over a fortnight ago, Senator Matt Canavan was talking on a program fronted by Breitbart founder and Trump adviser Steven Bannon. Last week, he was on the ABC’s Q&A, where he was handed a national audience.

Mainstream media thrive on the melodrama provided by the staging of stark disagreement. The advocate of locking down the population for its own safety while infections run at over 300 per day in the country’s largest city needs to be confronted with a “let the virus run free” type. For the sake of “representation” and “balance”, the right-wing Institute of Public Affairs gets media opportunities quite out of proportion to any real public interest in its libertarian ideas.

The revival of Hanson’s political career in the mid-2010s was fundamentally dependent on the opportunities provided by commercial television, where her extreme views and opinions could be guaranteed to draw attention, viewers and advertising coin. Similarly, she and her advisers have always understood the media value of the political gimmick – such as appearing in parliament in a burqa.

Peter Mathew/AAP

To read the Australian section of The Spectator these days – I realise I am among a small minority who do – is to encounter a fragment of the right-wing commentariat that seems out of sorts with the Coalition government under Scott Morrison.

Indeed, it seems almost as upset with him as it was with its previous dangerous radical enemy, Malcolm Turnbull. In the July 17 issue, it asserted:

The Liberal Party is adrift, a large, ugly and ungainly tanker that has slipped its moorings and is taking on water as it flounders in a turbulent and unpredictable sea. On the bridge, an ineffectual captain navigates by opinion polls and focus groups, with sinister factional bosses whispering in his ear.

Commentators of this kind – and the editorial goes on to praise Ruddick as “one of the great thinkers of the modern Liberal Party over three decades” – seem almost as worried these days by Morrison as by “Dictator Dan” Andrews in Melbourne. Perhaps more so. They are worried by the authoritarianism, the big spending and the flirtation with zero-carbon ideas. Above all, they are worried by what they call the lies and deceit about COVID.

The basic idea in these circles is that most politicians and their health advisers have persistently exaggerated the risks of the disease. They have done so because they fundamentally hate individual freedom, care nothing for ordinary people and are cosseted from having to earn their bread in the real economy. And, once again, here are ideas you will find among certain commentators in the mainstream media, not only in strange corners of the internet or in low-circulation, right-wing magazines.

Read more:

How the pandemic has brought out the worst — and the best — in Australians and their governments

In one sense, they are the Australian backwash of Brexit and Trump, mouthing the slogans of British Europhobes, Hungarian despots, Dixieland governors and Republican Party senators – and Steve Bannon.

But like these right-wing populist counterparts elsewhere, they are also political adventurers and entrepreneurs, seeking to build new constituencies in unknown territory. Short on solutions, big on rhetoric and in the fortunate position of not having to run anything, the libertarian right is frustrated that most of the population seems content to do what it’s told.

At times, it sounds as shrill as the sectarians on the far left whom it sometimes resembles. But those on the right are more consequential because they have significant media sponsors, they exploit real fears and frustrations, and they can sound reasonable when they criticise government excess and authoritarianism.

That is because our governments have sometimes, during this crisis, practised excess and authoritarianism.![]()

Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.