KCNA via KNS/AP

Tilman Ruff, University of Melbourne

Today, many around the world will celebrate the first multilateral nuclear disarmament treaty to enter into force in 50 years.

The UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was adopted at the United Nations in 2017 and finally reached the milestone of 50 ratifications in October. The countries that have signed and ratified include Austria, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, South Africa, Nigeria and Thailand.

The treaty completes the suite of international bans on all major weapons considered unacceptable because of their indiscriminate and inhumane effects, including anti-personnel landmines, cluster munitions, biological and chemical weapons.

The countries that have signed the TPNW were fed up with over half a century of the nuclear-armed states flouting their obligation to rid the world of their weapons. They have asserted the interests of humanity and global democracy in a way the nuclear-armed states were powerless to stop.

It is certainly long overdue for the most cruel and destructive weapons of all — nuclear weapons — to be banned. But this treaty is a sign of hope — a necessary and important step toward a less destructive planet.

What will the treaty do?

The aim of the treaty is a comprehensive and categorical ban of nuclear weapons. It binds signatories not to develop, test, produce, acquire, have control of, use or threaten to use nuclear weapons.

States also cannot “assist, encourage or induce” anyone to engage in any activity prohibited under the treaty — essentially anything to do with nuclear weapons.

The TPNW strengthens the current nuclear safeguards found in the 1970 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons by requiring all states that join to have comprehensive provisions in place and not allowing states to weaken their existing safeguards.

The treaty provides the first legally binding multilateral framework for a process by which all nations can work toward eliminating nuclear weapons.

For instance, states with another nation’s nuclear weapons stationed on their territory must remove them.

States with nuclear weapons can “destroy then join” the treaty, or “join then destroy”. They must irreversibly dismantle their weapons, as well as the programs and facilities to produce them, subject to agreed timelines and verification by an international authority.

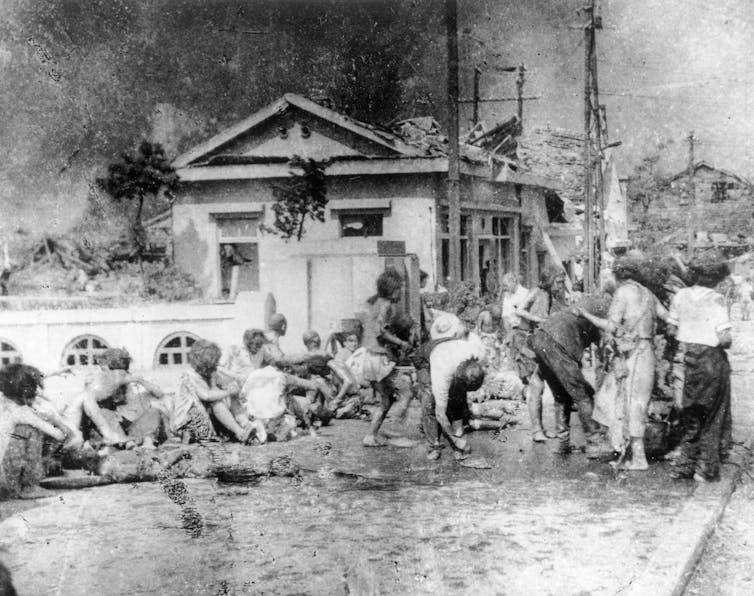

Further, the TPNW is the first treaty to commit member nations to provide long-neglected assistance for the victims of atomic bombs and weapon testing. It also calls for nations to clean up environments contaminated by nuclear weapons use and testing, where feasible.

Nuclear-armed states have been put on notice

Currently, 86 nations have signed the TPNW, and 51 have ratified it (meaning they are bound by its provisions). The treaty now becomes part of international law, and the number of signatories and ratifications will continue to grow.

However, none of the nine nuclear powers — the US, China, Russia, France, the UK, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea — have yet signed or ratified the treaty.

Many other countries that rely on other nations’ nuclear weapons for their security, such as the 27 members of NATO, Australia, Japan and South Korea, have also not signed.

So, why does the treaty matter given these states currently oppose it? And what effect can we expect the treaty to have on them?

While any treaty is technically only binding on the states that join it, the TPNW establishes a new international legal standard against which all nuclear policies will now be judged.

The treaty, in short, is a game-changer, and the nuclear-armed and dependent countries have been put on notice. They know the treaty jeopardises their claimed right to continue to threaten the planet with their weapons, as well as their plans to modernise and maintain their nuclear arsenals indefinitely.

The strength of their opposition is a measure of the treaty’s importance. It will have implications for everything from defence policies and military plans to weapons manufacturing to financial investments in the companies that profit from making now illegal nuclear weapons.

For example, a growing number of banks, pension funds and insurance companies around the world are now divesting from companies that build nuclear weapons.

These include the Norwegian Pension Fund (the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund), ABP (Europe’s largest pension fund), Deutsche Bank, Belgium’s largest bank KBC, Resona Holdings, Kyushu Financial Group and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group in Japan, and the Japanese insurance companies Nippon Life, Dai-ichi Life, Meiji-Yasuda and Fukoku Mutual.

Read more:

Ban the bomb: 70 years on, the nuclear threat looms as large as ever

A ‘dangerous’ belief nuclear weapons enhance security

Would joining the treaty mean nations like Australia, Japan, South Korea and NATO members would have to end their military cooperation with nuclear-armed states like the US?

No. There is nothing in the TPNW that prevents military cooperation with a nuclear-armed state, provided nuclear weapons activities are excluded.

Countries like New Zealand and Kazakhstan have already demonstrated that joining the treaty is fully compatible with ongoing military cooperation with, respectively, the US and Russia.

In a recent letter urging their governments to join the treaty, 56 former presidents, prime ministers and defence and foreign ministers from these nations said

By claiming protection from nuclear weapons, we are promoting the dangerous and misguided belief that nuclear weapons enhance security.

As states parties, we could remain in alliances with nuclear-armed states, as nothing in the treaty itself nor in our respective defence pacts precludes that.

But we would be legally bound never under any circumstances to assist or encourage our allies to use, threaten to use or possess nuclear weapons. Given the very broad popular support in our countries for disarmament, this would be an uncontroversial and much-lauded move.

The signatories include two former NATO secretaries-general, Willy Claes and Javier Solana.

Ban treaties have been proven to work with other outlawed weapons — landmines, cluster munitions and biological and chemical weapons. They have provided the basis and motivation for progressive efforts to control and eliminate these weapons. They are now significantly less produced, deployed and used, even by states that haven’t joined the treaties.

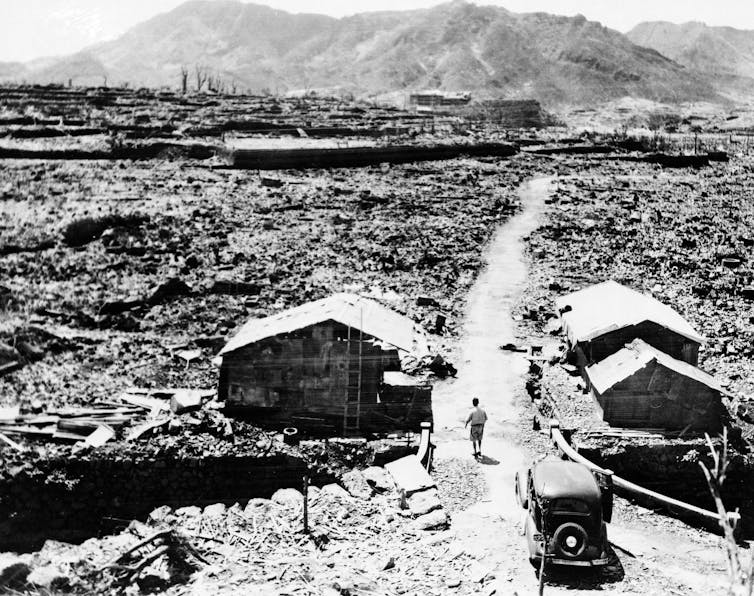

We can achieve the same result with nuclear weapons. As Hiroshima survivor Setsuko Thurlow said at the UN after the treaty was adopted,

This is the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons.

Tilman Ruff, Honorary Principal Fellow, School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.