Australia

Sweden

Japan

Mexico

USA

Australia

Sweden

Japan

Mexico

USA

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

Scott Morrison will participate in an Extraordinary Leaders’ Summit of the G20 called for next week to discuss the international coronavirus crisis.

The teleconference has been convened by the Saudi G20 Presidency.

A statement from the presidency on Wednesday said the virtual G20 leaders summit aimed to “advance a coordinated response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its human and economic implications.”

“The G20 will act, alongside international organisations, in any way deemed necessary to alleviate the impact of the pandemic.”

“G20 leaders will put forward a coordinated set of policies to protect people and safeguard the global economy,” the statement said.

It said the summit would build on the work of G20 finance ministers and central bank governors, and health, trade, and foreign affairs officials to develop detailed actions needed.

Earlier Report:

The federal government’s new sweeping measures in the coronavirus crisis include a ban on non-essential indoor gatherings of 100 people or more, advice that no Australian should travel abroad, and strict restrictions on visitor access to aged care facilities.

The measures, announced by Prime Minister Scott Morrison early Wednesday, take the battle to contain the spread of the virus to a new level but do not include the closure of the nation’s schools, or foreshadow a general community shutdown.

Morrison said the second stage economic package the government is now working on would be to “cushion” the impact of the measures put in place – it would focus on strengthening the “safety net” for individuals and small businesses.

He said there had been a big “gear change” at the weekend “when we were moving to far more widespread social distancing and bans on gatherings”.

Morrison berated hoarders in the strongest language. “Stop doing it. It’s ridiculous. It’s un-Australian[…]also, do not abuse staff. We’re all in this together. People are doing their jobs.”

“They’re doing their best, whether they’re at a testing clinic this morning, whether they’re at a shopping centre.”

Travel advice has been lifted to the highest level – which is unprecedented – with Australians, regardless of their destination, age or health, being told they should not travel overseas.

The new measures, which were approved late Tuesday night by the federal-state “national cabinet”, also include the cancellation of ANZAC Day events, which was mostly an endorsement of action already taken by the RSL. There will be a national service, but without a crowd. Small streamed ceremonies involving officials at state level may be held

“Life is changing in Australia, as it is changing all around the world,” Morrison told a Canberra news conference in which he and Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy stood the required social distance apart.

“Life is going to continue to change,” he said, but he also stressed the need to keep the country operating.

Morrison emphasised that measures had to be for the long term because the crisis was set to last at least six months.

Murphy said “a short-term two to four week shut down of society is not recommended by any of our experts. It does not achieve anything. We have to be in this for the long haul.”

On the sensitive issue of the schools, on which there’s been a lot of pressure for closure, Morrison highlighted his own family.

“I am telling you that, as a father, I’m happy for my kids to go to school. There’s only one reason your kids shouldn’t be going to school and that is if they are unwell.”

The advice from health experts, and the view of the premiers and chief ministers has been that schools should be kept open. Morrison said that closure would mean a “30% impact on the availability of health workers.”

The government has also decided that 20,000 international student nurses who are in Australia will be able to stay to help with the local crisis.

Aged cared facilities will not ban visits but will put in place restrictions to protect residents, who form the most high risk portion of the population. Morrison, who recently lost his own father, said he knew these would be difficult for families.

Visits will be restricted to a maximum of two people at any one time a day and no large group visits or social activities will be allowed

There will be special arrangements for the families of end-of-life patients.

The human biosecurity emergency provision of the Biosecurity Act was put into force early Wednesday. This gives draconian powers to the federal government, and the action matches the state governments’ emergency declarations.

Morrison said the advice was that plane travel within the country did not present a high risk – the risk was where people had come from and were going to. People are told not to visit remote communities, to protect vulnerable indigenous citizens.

The ban on non-essential indoor gatherings of more than 100 excludes a range of places such as shopping centres; public transport; medical and healthcare facilities; office buildings; factories; construction sites, and mining sites.

States and territories are looking at rules for non-essential indoor gatherings of fewer than 100 people, such as cinemas, restaurants, clubs, weddings, and funerals. This will be considered when the national cabinet meets on Friday. There may be significant changes to the operation of these facilities, such as decreasing maximum capacity, or increasing space available.

The beleaguered aviation industry is being promised relief, with a waiver of fees and charges.

Both Morrison and Murphy strongly reinforced the need for “social distancing”

Murphy said “it is every individual Australian’s responsibility to practice good social distancing. Keep away from each other where possible. Practice really good hand hygiene.”

“No more handshaking. No more hugging – except in your family.”

So far, 80,000 tests have been conducted, and the government is sourcing further testing kits.

The focus for the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments is the health and wellbeing of Australians and their livelihoods, ensuring that Australia is positioned to emerge strong and resilient from this global pandemic crisis.

Leaders met last night for the second National Cabinet meeting and agreed to further actions to protect the Australian community from the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19).

As part of our efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19 in Australia, the National Cabinet has accepted further restrictions on gatherings.

The National Cabinet has accepted the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) advice that non-essential indoor gatherings of greater than 100 people (including staff) will no longer be permitted from Wednesday 18 March 2020.

An indoor gathering refers to a gathering within a single enclosed area (i.e. an area, room or premises that is or are substantially enclosed by a roof and walls, regardless of whether the roof or walls or any part of them are permanent, temporary, open or closed).

This does not apply to essential activities such as public transportation facilities, medical and health care facilities, pharmacies, emergency service facilities, correctional facilities, youth justice centres or other places of custody, courts or tribunals, Parliaments, food markets, supermarkets and grocery stores, shopping centres, office buildings, factories, construction sites, and mining sites, where it is necessary for their normal operation (although other social distancing and hygiene practices may be required in these settings).

The states and territories will give further consideration to practical guidance and rules for non-essential indoor gatherings of fewer than 100 people (including staff) such as cinemas, theatres, restaurants/cafes, pubs, clubs, weddings and funerals. This will be considered at the next National Cabinet meeting on Friday 20 March 2020. In the meantime these venues should continue to apply social distancing and hygiene practices.

This includes being able to maintain a distance of 1.5 metres between patrons.

Hand hygiene products and suitable waste receptacles need to be available, with frequent cleaning and waste disposal.

This may require significant changes to the operation of some venues, such as reducing the maximum capacity or increasing the space available.

Settings like gyms, indoor fitness centres and swimming pools are not required to close at this time providing they meet these requirements for social distancing and hand hygiene. Such venues should take actions to ensure regular high standards of environmental cleaning take place.

Outdoor events of fewer than 500 attendees may proceed. There are general measures that all events should follow, including:

In a given occupied space, there must be no more than one person per four square metres of ground space.

Availability of hand hygiene products and suitable waste receptacles, with frequent cleaning and waste disposal.

Food markets are exempt from the 500 person limit, however must undertake additional measures, such as control of patronage level numbers or stall density reduction to decrease the risk of COVID-19 transmission.

There may be other gatherings that are considered essential and it is at the discretion of the individual state and territory Chief Medical Officers or equivalent to assess each on their merits, and determine whether they can continue if mitigated by social distancing measures.

National Cabinet agreed that all Australians should only consider travelling when it is essential. If unwell, people must stay at home, unless seeking medical care.

National Cabinet agreed that public transport is essential and that AHPPC advice should apply in relation to public transport (trains, trams, buses, ferries), taxi and ride share vehicles and transport of vulnerable populations, with particular attention given to cleaning and hygiene.

National Cabinet agreed that domestic air travel is low risk. The issue of where people are travelling to and sensitive locations where travel should be restricted, will be developed with advice of states and territories.

The National Cabinet will further consider social distancing arrangements for domestic transport at its next meeting on Friday 20 March 2020.

In all cases, appropriate social distancing and hygiene practices should be applied.

Anzac Day is an important commemoration where we demonstrate our respect and admiration for Anzacs past and present. But the way we commemorate Anzac Day this year will need to change.

The National Cabinet has agreed that Anzac Day ceremonies and events should be cancelled due to the high proportion of older Australians who attend such events and the increased risk posed to such individuals. A small streamed/filmed ceremony involving officials at a state level may be acceptable. There should be no marches.

All Australian-led international Anzac Day Services will be cancelled for 2020 given international travel restrictions and restrictions on public gatherings.

The Australian War Memorial will aim to conduct a national televised Dawn Service with no general public attendance.

State and Territory Governments and the RSLs will work together on local community arrangements to commemorate Anzac Day.

The National Cabinet has strongly endorsed the AHPPC advice against the bulk purchase of foods, medicines and other goods.

We strongly discourage the panic purchase of food and other supplies. While some advice has been provided to have a small addition of long shelf life products in the case of illness there are a range of mechanisms in place to support people in self-isolation, including food and other deliveries. AHPPC notes that the risk of individual Australians being asked to quarantine in coming weeks is low, and encourages individuals to plan with friends and family in the event of the need to isolate. We recognise the importance of supply lines to remote communities.

As the transmission of COVID-19 increases rapidly, it is our priority to protect and support elderly and vulnerable Australians. Aged care is a critical sector that faces staffing challenges as existing staff are either subject to self-isolation requirements due to COVID-19 or are unable to attend work.

The National Cabinet has agreed to the recommendations by the AHPPC to enhanced arrangements to protect older Australians in Residential Aged Care Facilities and in the community

The following visitors and staff (including visiting workers) should not be permitted to enter the facility:

Those who have returned from overseas in the last 14 days;

Those who have been in contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19 in the last 14 days;

Those with fever or symptoms of acute respiratory infection (e.g. cough, sore throat, runny nose, shortness of breath); and

Those who have not been vaccinated against influenza (after 1 May)

Visitors

Aged care facilities should implement the following measures for restricting visits and visitors to reduce the risk of transmission to residents, including:

Limiting visits to a short duration;

Limiting visits to a maximum of two immediate social supports (family members, close friends) or professional service or advocacy at one time, per day;

Visits should be conducted in a resident’s room, outdoors, or in a specific area designated by the aged care facility, rather than communal areas where the risk of transmission to residents is greater;

No large group visits or gatherings, including social activities or entertainment, should be permitted at this time;

No school groups of any size should be allowed to visit aged care facilities.

Visitors should also be encouraged to practise social distancing practices where possible, including maintaining a distance of 1.5 metres.

Children aged 16 years or less must be permitted only by exception, as they are generally unable to comply with hygiene measures. Exemptions can be assessed on a case-by-case basis, for example, where the resident is in a palliative care scenario.

Measures such as phone or video calls must be accessible to all residents to enable more regular communication with family members. Family and friends should be encouraged to maintain contact with residents by phone and other social communication apps, as appropriate.

Managing illness in visitors and staff

Aged care facilities should advise all regular visitors and staff to be vigilant for illness and use hygiene measures including social distancing, and to monitor for symptoms of COVID-19, specifically fever and acute respiratory illness. They should be instructed to stay away when unwell, for their own and residents’ protection.

Given the high vulnerability of this particular group, aged care facilities should request that staff and visitors provide details on their current health status, particularly presentation of symptoms consistent with COVID-19. Screening for fever could also be considered upon entry.

These additional measures should be implemented in order to better protect residents and prompt individuals entering the aged care facility to consider their current state of health prior to entry. Both individuals and management need to take responsibility for the health of visitors and staff at facilities to protect our most vulnerable community members.

These are the recommendations of the AHPPC, individual facilities may choose to implement additional measures as they see fit for their circumstances.

Staff should be made aware of early signs and symptoms of COVID-19. Any staff with fever or symptoms of acute respiratory infection (e.g. cough, sore throat, runny nose, shortness of breath) should be excluded from the workplace and tested for COVID-19. Staff must report their symptoms to the aged care facility.

Further information is available at: https://www.health.gov.au/committees-and-groups/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc

The National Cabinet has accepted the advice of the AHPPC that schools should remain open at this time.

Specifically the National Cabinet has agreed that “pre-emptive closures are not proportionate or effective as a public health intervention to prevent community transmission of COVID-19 at this time.”

National Cabinet also noted AHPPC advice that “More than 70 countries around the world have implemented either nationwide or localised school closures, at different times in the evolution of the local COVID-19 epidemic, however it should be noted the majority of these have not been successful in controlling the outbreak. Some of these countries are now considering their position in relation to re-opening schools.”

The National Cabinet noted that boarding schools are “at high risk of transmission” and encouraged boarding schools and parents to “consider the risks versus the benefits of a student remaining in boarding school”.

_The National Cabinet accepted the advice that university and higher education “should continue at this time” with risk mitigation measures, including working from home arrangements where effective. As with boarding schools, group student accommodation “presents a higher risk” that warrants consideration of “closing or reducing accommodation densities” if risk mitigation is not possible. _

The National Cabinet accepted advice from the AHPPC that community sporting activities could continue with involvement from essential participants (players, coaches, match officials, staff and volunteers involved in operations, and parents and guardians of participants).

This advice follows ongoing consultation with sporting organisations which has resulted in guidelines being prepared for community sporting organisations. The guidelines provide relevant advice on change room access, physical contact, travel, and social distancing and hygiene practices.

Furthermore, it has been acknowledged that contact sports have a greater risk of transmission than other sports, and as such, should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

All sporting codes should seek public health advice applicable to their codes, and take into account outdoor mass gathering issues.

Further work will be progressed by Friday 20 March 2020 and will include additional support for vulnerable Australians including indigenous communities and NDIS participants.

The Department of Social Services (DSS), National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) and NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (NDIS Commission) are working together in preparation to respond to COVID-19 and its impact on the NDIS.

The National Cabinet noted that Commonwealth, States and Territories were implementing emergency powers under respective legislation in order to be able to deal with the spread of COVID-19 as quickly and flexibly as possible.

The Governor-General has accepted the Commonwealth Government’s recommendation that he declare a “human biosecurity emergency” under the Biosecurity Act 2015 given the risks COVID-19 poses to human health and the need to control its spread in Australia.

That declaration would allow the Health Minister to issue targeted, legally enforceable directions and requirements to combat the virus.

The declaration was recommended by the Chief Medical Officer in his capacity as the Director of Human Biosecurity.

The first emergency requirement that will be made under the declaration is to formally prohibit international cruise ships from entering Australian ports for an initial 30 days, which provides additional legal support for the decision announced on Sunday 15 March 2020.

The Commonwealth Government will relax international student nurse visa work conditions to provide workforce continuity for aged care facilities, home care providers and other health care workers. This will allow international student nurses and other aged care workers to work more than the 40 hours a fortnight that they are currently. This measure will be examined on an ongoing basis. There are currently around 900 approved providers of residential aged care employers and around 1,000 approved providers of Home Care Packages. There are currently around 20,000 international student nurses studying in Australia.

The National Security Committee of Cabinet has decided to raise the advice for all overseas travel to the highest level. Our advice to all Australians – regardless of your destination, age or health – is do not travel overseas at this time.

This our highest travel advice setting – Level 4 of 4.

The decision reflects the gravity of the international situation arising from the COVID-19 outbreak, the risks to health and the high likelihood of major travel disruptions.

We also now advise Australians who are overseas who wish to return to Australia, to do so as soon as possible by commercial means. Commercial options may quickly become limited.

Anyone arriving in Australia from overseas, including Australians citizens and permanent residents, will be required to self-isolate for 14 days from the date of arrival.

We have issued this advice for several reasons:

There may be a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 overseas.

Health care systems in some countries may come under strain and may not be as well-equipped as Australia’s or have the capacity to support foreigners.

Overseas travel has become complex and unpredictable. Many countries are introducing entry or movement restrictions. These are changing often and quickly, and your travel plans could be disrupted.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade will do what it can to provide consular advice and assistance, but DFAT’s capacity to do so may be limited by local restrictions on movement, and the scale of the challenges posed by COVID-19. These challenges vary and the situation is changing rapidly.

Australians who cannot, or do not want to, return home should follow the advice of local authorities and minimise their risk of COVID-19 exposure by self-isolating.

The Commonwealth Government has announced an aviation package for the refunding and ongoing waiving of a range Government charges on the industry including aviation fuel excise, Airservices charges on domestic airline operations and domestic and regional aviation security charges.

These measures are in response to unprecedented and likely sustained period of falling international and domestic aviation demand related to the impact of COVID-19.

The total cost of the measures are estimated to be $715 million, with an upfront estimated benefit of $159 million to our airlines for reimbursement of applicable charges paid by domestic airlines since 1 February 2020.

The National Cabinet expressed their thanks to Australia’s world-class health professionals for their continued efforts in restricting the spread of the virus and saving lives.

Leaders also thanked all Australians for playing their part in following the health guidance and complying with the strong measures in place to respond to COVID-19.

Leaders called on the community to remain calm. While there have been some temporary, localised food and grocery distribution delays, there are sufficient stocks in Australia. Violent or anti-social behaviour would not be tolerated.

As a National Cabinet, we will continue to come together as a united team to ensure our collective response remains proactive and targeted, but we all have a responsibility to each other in protecting our community.

All Australians must continue to be vigilant and play their part to slow the spread of COVID-19 and protect vulnerable members of our community, including the elderly.

The National Cabinet urged Australians to continue to adhere to the health guidance on hygiene and personal social distancing, including avoiding any non-essential travel. Leaders also acknowledged the many businesses that have stepped up and allowed staff to work from home where practical. These early actions are critical in delaying the peak of the outbreak and ensuring our health system response remains strong.

The Commonwealth Chief Medical Officer, Professor Brendan Murphy, provided the National Cabinet with an overview of the current situation in Australia and overseas. The National Cabinet noted the continued development of international responses. Australia, like many other nations, is seeing an increase in community transmission. We are one of the best prepared nations and we remain united, focussed and ready to respond to any sustained escalation.

The National Cabinet also considered the Chief Medical Officer’s advice on rates of community testing. More than 80,000 tests have already been undertaken in Australia. Further testing stocks have been secured and the Doherty Institute in Melbourne has developed an alternative testing process. This ensures Australia has a diverse range of tests and can protect supply of testing in the event there is a shortage in materials or components of some testing kits.

All Australians should continue to closely follow the expert medical advice – and ensure testing is only sought for COVID-19 where it meets the relevant clinical criteria. As we enter the colder months there may be a number of other viruses that enter our community, so there is a need to prioritise testing of people.

The National Cabinet noted that in order to protect older Australians and vulnerable communities in the weeks and months ahead, Australia may see even more restrictions put on social movements. We need all Australians to please look out for each other and to follow the medical advice.

The National Cabinet will be meeting again on Friday 20 March 2020 to discuss implementation arrangements for indoor gatherings and domestic transport.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Caitlin Byrne, Griffith University

What a weekend it’s been: global leadership, diplomacy and theatrics, all at play on the world stage. US President Donald Trump – never one to shy away from the spotlight — has dominated. Significant breakthroughs, including a pause in the escalating China-US trade war and the resumption of dialogue between the US and North Korea, have been achieved.

One might question the strategy and motivations behind Trump’s latest diplomatic engagements. Known for his unorthodox approach to diplomacy, Trump’s latest activities are more likely driven by the prospect of a fight in the 2020 US elections than a genuine concern for regional and global stability. Trump’s turn towards dialogue has averted the immediate disaster of a trade war and confrontation with North Korea, but the longer-term implications point to a more significant shake-up in global diplomacy.

As host of the 2019 G20 summit, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is to be credited for his efforts in bringing global leaders together under what appeared to be difficult circumstances.

It was always going to be a tough meeting. Overshadowed by the US-China trade war, and set against a global backdrop of widening political fault lines, seething populism and fraying institutions, Abe certainly had his work cut out for him.

Read more:

Trade war tensions sky high as Trump and Xi prepare to meet at the G20

Just bringing together the leaders and other officials from 19 of the world’s biggest economies, plus the European Union, for a summit on global economic governance was, in itself, a major achievement. They were joined by a raft of invited guests, including the leaders of Singapore, Vietnam and Thailand, as well as representatives of key international organisations.

The summit delivered expected consensus support for “strong, sustainable, balanced and inclusive economic growth”, alongside renewed commitments to reform the World Trade Organisation and agreement on key initiatives on digital innovation and e-commerce, financial inclusion for ageing populations, and marine plastics.

More importantly, it provided the much-needed platform for US-China dialogue, bringing the escalating trade war to a halt.

Ultimately, though, the G20 gains were limited. The final communiqué reflected the deep political tensions globally at the moment and the overriding domestic focus of many leaders. For example, it stopped short of affirming the G20’s customary commitment to anti-protectionist measures and included watered-down language on climate change action.

One might be forgiven for mistaking the leaders’ summit for a glorified photo opportunity. G20 pics – ranging from the rambling family photos of leaders and spouses to awkward moments on the sidelines — dominated the weekend Twittersphere.

Of course, optics matter, and the images revealed much about the diversity and dynamics at play within this “premier” economic forum. Trump’s friendly interactions with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, for instance, raised eyebrows and ire at home.

But it’s not all about the photo opps. The G20 leaders’ summit is the culmination of months of intense negotiations, and most importantly reinforces the underlying habits of cooperation so desperately needed for ongoing global economic stability.

As with any major summit, the G20 gathering offers the opportunity for leaders to engage in bilateral or minilateral discussions. For many, this is the main event, and for Abe, especially, the stakes on the sidelines at this G20 were high.

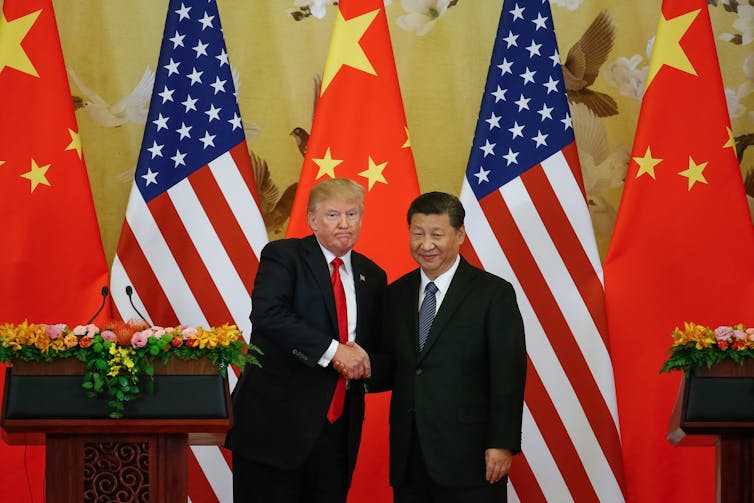

Saturday’s bilateral meeting between Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping did not disappoint, with both leaders agreeing to resume trade talks, stalled since the last G20 in Buenos Aires. Notably, Trump announced his suspension of some US$300 billion in threatened tariffs and eased restrictions on US companies selling components to Chinese telco, Huawei.

Read more:

US-China relations are certainly at a low point, but this is not the next Cold War

Other G20 sideline events, including Trump’s bilateral with Putin created their own drama, but it was Trump’s Saturday morning tweet suggesting a spontaneous visit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un during his subsequent trip to Korea, that caught everyone off guard.

And with that, arrangements fell miraculously into place for Trump to take a historic first step for a sitting US president into North Korea, and for Kim and Trump to spend an hour in conversation in Freedom House on the South Korean side of the demilitarized zone.

Importantly, the two have now agreed to further talks intended to advance their ongoing denuclearization negotiations. Spectacle aside, there may well be positives to come from this interaction, but for the moment the endgame just isn’t clear.

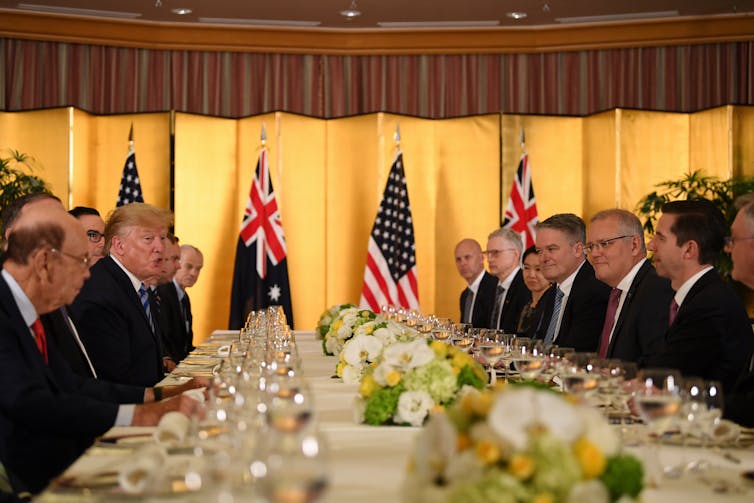

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison performed remarkably well at his second G20 leaders’ summit, marking a positive turn from last time round.

To be fair, Morrison attended his first G20 summit in November just three months into his term as prime minister following the Coalition leadership spill. He was unknown and inexperienced at the time.

Read more:

In his first major foreign policy test, Morrison needs to stick to the script

In Japan, Morrison was attending his first G20 as Australia’s elected leader, with decent summitry experience and far more established relationships with his global counterparts in place. His key message – that a US-China trade war was in nobody’s interests – was well-prepared, and it resonated with key G20 counterparts.

Other highlights for Morrison included his dinner on the eve of the summit with Trump. While the press pool may have been unimpressed, the fact that this was Trump’s first bilateral event of the summit is significant, even if it was, as some suggest simply to fill a gap in Trump’s program. Trump’s reflection on the US alliance with Australia, and Morrison’s election win with Australia was replete with praise.

More importantly, though, Morrison’s win on curbing terrorist activities via social media was an important contribution to the summit outcome. G20 leaders were unanimous in their backing for the proposal that would increase pressure on tech giants like Facebook to block or remove the spread of violent extremism online.

The fact that Morrison shared news of the outcome with New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern added to the credibility of the concept within the G20 grouping and lifted its profile at home.

In all, the G20 summit was an important exercise in diplomacy and resulted in a positive outcome for Abe. This sort of cooperation is so desperately needed if the institutions, rules and norms underpinning economic governance are to carry any weight at all. And as Japan hands the G20 reins over to the 2020 host, Saudi Arabia, supporting diplomacy and cooperation will be more important than ever.

Trump’s sideshow-style diplomacy certainly stole the limelight. The resumption of dialogue with both China and North Korea reaffirms the necessary place of diplomacy in the region. But Trump is navigating dangerous territory, and the lack of clear strategy, dubious motivations and self-serving tactics should have everyone – including his allies – on guard.![]()

Caitlin Byrne, Director, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tony Walker, La Trobe University

The United States and China have arrived at a temporary truce in a trade conflict that was threatening to further destabilise world equity markets, entrench a global slowdown and cause more damage to a rules-based international order.

Agreement by US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, to allow further negotiations before threatened tariff increases on Chinese imports come into effect is a welcome development.

However, this is a temporary respite, a short-term fix, not a long-term solution to myriad trade and other tensions that have put the US and China at odds with each other.

For their own purposes and in their own interests, Trump and Xi have come away from the Argentine capital with a deal that papers over differences that extend from China’s activities in the South China Sea to its mercantilist trade policies.

Read more:

Much at stake as Donald Trump and Xi Jinping meet at G20

As far as we know, China’s ruthless assertion of its sovereignty over disputed waters in the South China Sea was not a material subject for discussion in Buenos Aires except, possibly, in passing.

China’s rise and America’s relative decline ensure these global economic superpowers will continue to bump up against each other.

So, what was achieved and what are the prospects for an accord reached on the sidelines of the G20?

In their efforts to lower trade tensions and prevent a further erosion of global confidence, Trump and Xi agreed to a 90-day extension on the imposition of additional US tariffs on some US$200 billion of Chinese imports.

Trump had threatened to increase tariffs from 10% to 25% on an initial batch of Chinese imports from January 1. He had also flagged his intention to impose levies on another US$267 billion worth of imports if progress was not made in resolving broad-based trade differences.

A joint statement laid out a timeline for continuing negotiations. It reads:

Both parties agree that they will endeavour to have this transaction completed within the next 90 days. If, at the end of this period of time, the parties are unable to reach an agreement, the 10 percent tariffs will be raised to 25 percent.

In return for these temporary concessions, China agreed to:

… purchase a not yet agreed upon, but very substantial, amount of agricultural, energy, industrial, and other product from the United States to reduce the trade imbalance between the two countries. China has agreed to start purchasing agricultural product immediately.

China also agreed to crack down on sales of Fentanyl by making it a controlled substance. The US is battling an opioid crisis in which Fentanyl is a lethal component.

In retaliation for US trade actions, China had imposed duties on US$110 billion of imports. A principal component of this is soybeans, effectively killing one of America’s more lucrative export markets.

Trump has been under huge pressure from his Mid-Western rural heartland over a collapse in the Chinese market for American agricultural products.

The two sides also agreed to address structural problems in the trading relationship. These extend to five areas – forced technology transfer, intellectual property protection, non-tariff barriers, cyber intrusions and cyber theft.

These are highly complex issues and unlikely to be resolved in the short term, if at all.

In the wash-up of the Xi-Trump discussions it appears China has got more out of the deal than the US – at least for now. It has secured a stay of execution for the implementation of tariff increases and forestalled, for the time being, tariffs on an additional bloc of Chinese exports.

In return, it has agreed to buy unspecified quantities of US products and to talk about differences.

Trump’s willingness to compromise after months of bombast reflects pressures from a shellshocked grain-producing constituency and alarm on Wall Street at prospects of a full-blown trade war.

From Beijing’s perspective, China has demonstrated that its growing economic heft has enabled it to avoid the appearance of yielding to US pressure.

If not a “win-win” for China – as Chinese officials are fond of saying – it is certainly not a “lose-lose”.

In a statement at odds with months of fire-breathing rhetoric over China’s allegedly perfidious trade practices, Trump hailed his understanding with Xi. He said:

This was an amazing and productive meeting with unlimited possibilities for both the US and China.

For their part, Chinese officials were more circumspect.

Foreign Minister Wang Yi said the talks were conducted in a “friendly and candid atmosphere”. The presidents:

agreed that the two sides can and must get bilateral relations right… China is willing to increase imports in accordance with the needs of its domestic market and the people’s needs.

Impetus for a face-saving deal in Buenos Aires has been prompted by growing concerns about the global economy. The signs of a slowdown are clear. Trade volumes had begun to moderate in the third quarter, heightening worries of a global retrenchment.

On the sidelines of the G20, the International Monetary Fund’s managing director, Christine Lagarde, noted:

Pressures on emerging markets have been rising and trade tensions have begun to have a negative impact, increasing downside risks.

In its October Outlook statement, the IMF warned about threats to global growth due to trade disturbances.

In their final communique, G20 leaders danced around contentious issues on trade to accommodate American objections to having the word “protectionism” inserted in the document.

In the end, participants settled on the need for reform of the World Trade Organisation to describe a world trading system that is falling short of its objectives. Washington has been agitating for a review of the WTO to strengthen its dispute resolution and appeal procedures.

The US has also objected to a continuing description of China as a developing country, with concessions that enable it to take advantage of less developed country status in its access to global markets.

Read more:

As tensions ratchet up between China and the US, Australia risks being caught in the crossfire

On climate change, Washington separated itself from the other G20 members. All, except the US, reaffirmed their commitment to the Paris Agreement. The US announced in 2017 it was pulling out of Paris.

Foreign policy specialists will be sceptical about a de-escalation of trade hostilities given the range of issues bedevilling the US-China relationship.

Reflecting a hardening of US attitudes towards China, and in contrast to the optimism that had prevailed for much of the past two decades, Ely Ratner in Foreign Affairs notes:

Even if tariffs are put on hold, the United States will continue to restructure the US-China economic relationship through investment restrictions, export controls, and sustained law enforcement actions against Chinese industrial and cyber-espionage.

At the same time, there are no serious prospects for Washington and Beijing to resolve other important areas of dispute, including the South China Sea, human rights and the larger contest over the norms, rules and institutions that govern relations in Asia.

A stiffening view in the US towards China is shared more or less across the board. In those circumstances, a temporary ceasefire in Buenos Aires is unlikely to be sustained.![]()

Tony Walker, Adjunct Professor, School of Communications, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Christian Downie, Australian National University

Compared to other international organisations, the G20 would seem to be one of the weakest.

It has no formal mandate like the United Nations. It has no permanent staff or buildings like the World Bank. It certainly has no funds like the International Monetary Fund. It has no power to make formal rules that members must follow, nor to take action against states that fail to comply, like the World Trade Organisation.

So how does the G20 get anything done?

What has made it influential in tackling problems like the global financial crisis? Why is it tasked with addressing some of the most pressing global problems, such as climate change?

A big part of the answer is the sheer power of its members. But also vital is the G20’s informal structure, which provides members with significant flexibility, and its close working relationship with other international organisations that also have a seat at the G20 table.

The members of G20 pack enormous punch.

The group comprises 18 of the 21 nations with the biggest economies by gross domestic product, plus South Africa and the European Union.

This means there are effectively 43 countries with a stake in the G20. Together they account for about 85% of global gross domestic product, and about 65% of the world’s people.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/ZBqZE/2/

So when they agree to coordinate their national policies in a particular policy domain they can transform the global landscape.

In the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008, for example, G20 leaders agreed to coordinate their economic policies to ameliorate the worst impacts of the crash. Compared to previous crises of similar magnitude, the global economy recovered much more quickly than many anticipated. This is credited in large part to the G20’s role in expediting a coordinated response.

Although the G20 does not have its own permanent staff and resources, it is adept at enlisting the commitment and resources of other international organisations when it needs to.

Bodies such the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development are well-integrated into the G20’s negotiation processes.

Read more:

Explainer: who gets invited to the G20 summit, and why

These organisations often prove willing partners because they depend, to varying degrees, on the material and political support of G20 member states for their existence.

Take, for example, the Financial Stability Board, established by the G20 at its 2009 London summit in London.

The board works to promote the stability of the global financial markets by coordinating the work of national and international financial authorities. The G20 has relied on the board to take the lead on making large financial institutions less vulnerable to collapse, such as by forcing them to hold more capital, implementing tougher transparency standards, and monitoring their progress.

Similarly, the G20 has enlisted the OECD to help to make multinational companies pay tax; the United Nations Environment Programme to boost green finance; and the International Energy Agency to help address the problem of fossil-fuel subsidies.

That is not to say the G20 always delivers.

G20 leaders announced as far back as 2009 that they would phase out fossil-fuel subsidies. In ten years there has been limited progress.

Nevertheless, because global problems like climate change must be solved by collective action, the G20 remains a vital multilateral forum.

Particularly given G20 members account for 80% of the world’s primary energy demand, and about the same percentage of human-caused carbon emissions.

Read more:

We have so many ways to pursue a healthy climate – it’s insane to wait any longer

As a result, accelerated G20 cooperation could dramatically improve the prospects for a clean energy transition

Should they wish to do so, G20’s leaders have the capacity to achieve much more than talking. At their best they have the power to transform the rules that govern the globe.![]()

Christian Downie, Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tony Walker, La Trobe University

When US President Donald Trump meets his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, on the margins of the G20 summit in Buenos Aires between November 30 and December 1, nothing less than a reasonably healthy global trading system and continued economic growth will be on the table.

It is one of the more significant meetings between two global leaders in the modern era.

The encounter will recall the high-wire diplomacy between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s, which signalled the end of the Cold War and, as it happened, the disintegration of the former Soviet Union.

Or, before that, Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, which resulted in the signing of the Shanghai Communique and an end to decades of hostility between the United States and China.

Read more:

The risks of a new Cold War between the US and China are real: here’s why

World markets unnerved by an evolving trade conflict between the world’s two largest economies will take their cues from this encounter between an unpredictable US president and a Chinese leader who will not want to be seen to yield ground. Or, to give it an oriental description, lose face.

This is a fractious moment in world economic history.

Billions of dollars in global equity markets will rest on a reasonable consensus in the Argentine capital. The two sides will reach for a compromise that will enable relative stability to be restored to an economic relationship that is threatening to unravel.

Since a ragged outcome, or even failure, is in no-one’s interests, it is hard to believe Washington and Beijing will not seek to calm legitimate concerns about the risks of a full-blown trade war and its impact on global growth.

US-China trade tremors are already having an impact on growth projections for 2018-2020.

In its latest World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund reports the world economy is plateauing, partly due to trade tensions and stresses in emerging markets.

The IMF has scaled back its global growth projections from its July Outlook forecast for 2019 to 3.7% from 3.9%. It has marked down US growth by 0.2 percentage point to 2.5%, and China by a similar margin to 6.2%.

However, if trade disruptions persist, fallout will become more serious in 2020 with global growth projected to be down by 0.8%, and with it US and China growth down significantly.

Trade wars have consequences, including risks of a global recession.

All this invests the Trump-Xi encounter with more-than-usual significance. A bad outcome will heighten risks of an accelerating global slowdown.

In the lead-up to the G20, American and Chinese officials have been preparing the ground, with the Chinese side anxious to reduce tensions following a November 1 phone call between the two presidents.

But it is less clear that Washington is willing to ease pressure on China to liberalise further a foreign investment environment, seek ways to reduce a trade gap and make more conspicuous efforts to tone down concerns about Chinese pilfering of its intellectual property.

In a media briefing in Beijing, Chinese officials underscored China’s desire for a reasonable outcome in Buenos Aires. Wang Shouwen, a vice commerce minister, said:

We hope China and the US are able to resolve their problems based on mutual respect, benefits and honesty.

However, Trump is continuing to threaten further increases in tariffs on US$200 billion of Chinese imports now set at 10% but due to increase to 25% from January 1. He told The Wall Street Journal this week:

The only deal would be China has to open up their country to competition from the United States.

Trump also threatened to slap tariffs on an additional US$267 billion worth of Chinese imports if negotiations with Xi are unsuccessful:

If we don’t make a deal, then I’m going to put the US$267 billion additional on [at a tariff rate of either 10% or 25%].

This next batch of Chinese imports might include laptops and Apple iPhones, which are among China’s biggest exports to the US.

Further complicating the possibility of a satisfactory negotiation in Buenos Aires is a lingering dispute between the US and China over reforms to the World Trade Organisation to strengthen its dispute resolution and appeal mechanisms.

The US also objects to China’s continued description as a “developing country” under WTO rules. This includes provisions that are favourable to Chinese state-owned enterprises.

A collapse in efforts to reform the WTO would strike another blow at a multilateral trading system that is under more stress than at any time since globalisation gathered pace in the 1990s.

The US-China trade conflict, which is threatening to become a full-blown trade war with unpredictable consequences, cannot be separated from a more general deterioration in relations.

These were given expression last month by Vice President Mike Pence in a speech to the Hudson Institute, in which he lambasted China in a way that prompted talk of a new cold war.

Pence accused China of deploying:

… an arsenal of policies inconsistent with free and fair trade, including tariffs, quotas, currency manipulation, forced technology transfers, intellectual property theft and industrial subsidies handed out like candy. These policies have built Beijing’s manufacturing base, at the expense of its competitors – especially the United States.

The US trade deficit with China reached US$375 billion last year – nearly half the US global trade deficit.

None of this augurs well for a constructive resolution of US-China differences at the G20, although you might hope Trump’s approach would be tempered by concerns about the economic consequences of a conspicuous failure.

What seems most likely, given the stakes involved, is for officials from both countries to be tasked with responsibility for addressing a range of American concerns, with the aim of resetting the relationship.

This would seem to be a best-case scenario.

In the meantime, officials working on the draft of a final communique will be struggling to satisfy competing demands from G20 participants for clear-cut statements on protectionism and climate change.

These have been staples of such communiques since the G20 was formed ten years ago amid a global financial crisis.

Read more:

In the economic power struggle for Asia, Trump and Xi Jinping are switching policies

Washington is reportedly resisting an explicit call to fight protectionism. It is also demanding a watering down of the G20’s commitment to the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Consensus on these issues is proving elusive, further undermining efforts to address global challenges.

This underscores a dramatic shift in the global geopolitical environment since Trump gained office.

At the 2016 G20 summit in Hangzhou, world leaders agreed on a “rules-based, transparent, non-discriminatory, open and inclusive multilateral trading system with the World Trade Organisation playing the central role in today’s global trade”.

On climate, the G20 committed itself “to complete our respective domestic procedures in order to join the Paris Agreement”.

Two years later, a “rules-based” trading system is being shredded and the Paris Agreement is at risk of unravelling. These are troubled times, not helped by an American pullback from the stabilising role in global affairs it has played since the second world war.![]()

Tony Walker, Adjunct Professor, School of Communications, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Adam Triggs, Australian National University

“The secret to success is sincerity. Learn to fake that, and you’ve got it made.”

So goes an old gag. Many might be wondering something similar about this weekend’s G20 summit in Buenos Aires.

Each year the leaders of 20 of the world’s largest economies get together and make a lot of promises about working together to make the world a better place.

Are those promises kept? Are they just committing to do things they would have done anyway?

In short, does the G20 summit really make any difference?

Read more:

What on earth is the G20 and why should I care?

To find out, I interviewed dozens of politicians and officials from every G20 country about the influence and importance of the annual gathering since its first meeting in 2008.

My analysis shows most G20 promises are kept, and the forum really does exert a positive influence on its member nations.

Before I started my research I had reasons to be sceptical.

For example, at the G20’s second meeting, in London in 2009, the assembled leaders committed to fiscal stimulus packages worth a combined US$5 trillion in response to the 2008 global financial crisis. Central banks, like the Reserve Bank of Australia, also committed to aggressively cut interest rates.

The data shows they did what they promised. But didn’t countries have an incentive to do what they did anyway? What role did the G20 play?

Similarly in 2010, at the G20 meeting in Toronto, spooked by the European debt crisis, leaders promised to halve deficits by 2013 and stabilise debt-to-GDP ratios by 2016.

Many countries achieved this. But weren’t many countries, such as Australia, already on the “back to surplus” bandwagon? Did the G20 have any influence?

Was the G20 a real influence, or were countries just promising to do what they would have done anyway?

To find out, I interviewed a total of 63 senior politicians and officials from every G20 country.

They included former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd, former Australian treasurers Wayne Swan and Joe Hockey, US Federal Reserve chairperson Janet Yellen and her predecessor Ben Bernanke, former US Treasury secretary Jack Lew, Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda, and Bank of England governer Mark Carney.

I asked them whether they believed the G20 had influenced their and other countries’ policies.

The answer was yes – sometimes.

It depended on the country, the policy area and other things, like whether there was an international economic crisis. But the influence was definitely there.

According to Kevin Rudd, who oversaw the Australian government’s successful response to the global financial crisis:

The G20 played a positive role in the quantum of Australia’s fiscal stimulus.

Politicians from ten other countries said the same thing – verified with data, where possible.

Read more:

FactCheck: did Kevin Rudd help create the G20?

What about the G20’s influence on central banks?

These banks have domestic mandates. The Reserve Bank of Australia can’t refuse to change interest rates because it annoys New Zealand, for example. It must do what is best for the nation. What room is therefore left for G20 co-operation?

My research suggests the G20 does influence the thinking of central bankers and, through them, central bank policies.

“There is a lot of exchange of views in the G20 which I think is influential,” Ben Bernanke, who chaired the US Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014, told me.

Mark Carney, who was governor of the Bank of Canada before heading the Bank of England, said the G20 was “a useful forum in which central banks can explain the reasons for their policy decisions”.

What about those 1,000 structural reforms?

According to Joe Hockey, Australia’s treasurer from 2013 to 2015:

The G20 growth strategy process absolutely resulted in countries doing things differently, particularly by learning from one another.

US officials agreed, confirming they got the idea of an asset-recycling initiative – where governments lease existing infrastructure assets to private companies and invest the proceeds in new infrastructure projects – from Australia through the G20.

German officials said because of G20 commitments their government developed a financial literacy and education program to better equip Germany’s citizens, particularly young people, in their engagement with the financial system.

Russian officials said Vladimir Putin embraced their 2017-2020 reform agenda on female economic participation after learning about the benefits through the G20.

The G20 has also prevented nations embracing “beggar-thy-neighbour” policies that improve the country’s relative economic position by harming others. It has pressured members not to devalue their currencies in pursuit of competitive trade advantage. It has helped countries resist resorting to trade protectionism. It has defused tensions around controversial policies such as quantitative easing, and improved the communication of central banks on future policy changes.

Read more:

The G20’s economic leadership deficit

Janet Yellen, former chair of the US Federal Reserve, said she “genuinely took to heart” concerns expressed at the G20 about aspects of US policy.

The G20’s influence is not universal. Large countries are less influenced than smaller ones. Said a former senior US official:

Most Americans, and many in Congress, are proudly indifferent to what the rest of the world thinks.

Jacob Lew, US Treasury Secretary from 2013 to 2017, agreed:

There can be a backlash in the United States if you make the argument that you are doing something to comply with international rules.

The full results have been published by the Brookings Institution (available here).

So if commentators complain about the G20 being a pointless talkfest, just remember there is evidence to the contrary. It might not grab the headlines but the G20 plays an important role behind the scenes. We will be relying on it now, more than ever, to calm global tensions.![]()

Adam Triggs, Research fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tony Walker, La Trobe University

When G20 finance ministers met in Bali last week to review economic developments in the lead-up to the annual G20 summit, they could not ignore troubling signs in the global economy driven by concerns about an intensifying US-China trade conflict.

Last week’s slide in equities markets will have served as a warning – if that was needed – of the risks of a trade conflict undermining confidence more generally.

China’s own Shanghai index is down nearly 30% this year. This is partly due to concerns about a trade disruption becoming an all-out trade war.

Read more:

The risks of a new Cold War between the US and China are real: here’s why

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde’s call on G20 participants to “de-escalate” trade tensions or risk a further drag on global economic growth might have resonated among her listeners in Bali, but it is not clear calls to reason are getting much traction in Washington these days.

Uncertainties caused by a disrupted trading environment are already having an impact on global growth. In its latest World Economic Outlook, the IMF revised growth down to 3.7% from 3.9% for 2018-19, 0.2 percentage points lower than forecast in April.

The IMF is predicting slower growth for the Australian economy, down from a projected 2.9% this year to 2.8% next year. The May federal budget projected growth of 3% for 2018-19 and the following year.

Adding to trade and other tensions between the US and China are the issues of currency valuations, and a Chinese trade surplus.

In September, China’s trade surplus with the US ballooned to a record U$34.1 billion.

This comes amid persistent US complaints that Beijing has fostered a depreciation of the Yuan by about 10% this year to boost exports, which China denies.

These are perilous times in a global market in which the US appears to have shunned its traditional leadership role in favour of an internally-focused “America First” strategy.

So far, fallout from an increasingly contentious relationship between Washington and Beijing has been contained, but a near collision earlier this month between US and Chinese warships in the South China sea reminds us accidents can happen.

This is the background to a meeting at the G20 summit in Buenos Aires late in November between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping. That encounter is assuming greater significance as a list of grievances between the two countries expands.

US Vice President Mike Pence’s speech last week to the conservative Hudson Institute invited this question when he accused of China of “malign” intent towards the US.

Are we seeing the beginning of a new cold war?

The short answer is not necessarily. However, a further deterioration in relations could take on some of the characteristics of a cold war, in which collaboration between Washington and Beijing on issues like North Korea becomes more difficult.

By any standards, Pence’s remarks about China were surprising. He suggested, for example, that Chinese meddling in American internal affairs was more serious than Russia’s interventions in the 2016 president campaign.

He accused Beijing of seeking to harm Republican prospects in mid-term congressional elections and Trump’s 2020 re-election bid. This was a reference to China having taken its campaign against US tariffs to newspaper ads in farm states like Iowa.

Soybean exports to China have been hit hard by retaliatory tariff measures applied by Beijing in response to a first round of tariffs levied by the US.

“China wants a different American president,” Pence said.

This is probably true, but it could also be said that much of the rest of the world – not to mention half of the US population – would like a different American president.

All this unsteadiness – and talk of a “new cold war” – is forcing an extensive debate about how to manage relations with the US and China in a disrupted environment that seems likely to become more, not less, challenging.

Australian academic debate, including contributions from various “think tanks”, has tended to focus on the defence implications of tensions in the South China Sea for Australia’s alliance relationship with the US.

This debate has narrowed the focus of Australia’s concerns to those relating to America’s ability – or willingness – to balance China’s regional assertiveness.

This assertiveness increasingly is finding an expression in China’s activities in the south-west Pacific, where Chinese chequebook – or “debt-trap” – diplomacy is being wielded to build political influence.

Australian policymakers have been slow to respond to China’s push into what has been regarded as Australia’s own sphere of influence.

Read more:

Despite strong words, the US has few options left to reverse China’s gains in the South China Sea

Leaving aside narrowly-focused Australian perspectives, it might be useful to get an American view on the overarching challenges facing the US and its allies in their attempts to manage China’s seemingly inexorable rise.

Among American China specialists, few have the academic background and real-time government experience to match that of Jeffrey Bader, who served as President Barack Obama special assistant for national security affairs from 2009-2011.

In a monograph for the Brookings Institution published in September, Bader poses a question that becomes more pertinent in view of Pence’s intervention. He writes:

Ever since President Richard Nixon opened the door to China in 1972, it has been axiomatic that extensive interaction and engagement with Beijing has been in the US national interest.

The decisive question we face today is, should such broad-based interaction be continued in a new era of increasing rivalry, or should it be abandoned or radically altered?

The starkness of choices offered by Bader is striking. These are questions that would not have entered the public discourse as recently as a few months ago.

He cites a host of reasons why America and its allies should be disquieted by developments in China. These include its mercantilist trade policies and its failure to liberalise politically in the three decades since the Tiananmen protests.

However, the costs of distancing would far outweigh the benefits of engagement to no-one’s advantage, least of all American allies like Japan, India and Australia.

None of these countries, in Bader’s words, would risk economic ties with China nor join in a “perverse struggle to re-erect the ‘bamboo curtain’… We will be on our own”. He concludes:

American should reflect on what a world would be like in which the two largest powers are disengaged then isolated from, and ultimately hostile to each other – for disengagement is almost certain to turn out to be a way station on the road to hostility, he concludes.

Bader has been accused of proffering a “straw man argument’’ on grounds that the administration is feeling its way towards a more robust policy, and not one of disengagement. But his basic point is valid that Trump administration policies represent a departure from the norm.

At the conclusion of the IMF/World Bank meetings in Bali, Christine Lagarde added to her earlier warnings of “choppy” waters in the global economy stemming from trade tensions and further financial tightening. She said:

There are risks out there in the system and we need to be mindful of that…bIt’s time to buckle up.

That would seem to be an understatement, given the unsteadiness in the US-China relationship and global geopolitical strains more generally.![]()

Tony Walker, Adjunct Professor, School of Communications, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Giovanni Di Lieto, Monash University and David Treisman, Monash University

It is clear that trade protectionism is alive and well in the G20, whose countries account for 78% of global trade. But this protectionism isn’t in the form of tariffs, which are duties placed on imports, making imported goods and services more expensive than they would be otherwise. Instead, trade protectionism is being pursued through “non-tariff barriers” such as import quotas, restrictive product standards, and subsidies for domestic goods and services.

This shows that while countries are reducing the obvious barriers to trade, like tariffs, they are still pursuing stealth forms of trade protectionism through non-tariff barriers.

Our research on trade protectionism in the services sector shows that the lower the barriers to trade, the greater company profits. Lower trade barriers create a larger market for Australian goods and services.

We also found that increased domestic regulation leads to higher profits as standards improve across the sector. For Australia this is very significant because the services sector employs four out of five Australians and accounts for 20% of Australia’s total exports.

Eliminating trade protectionism is also good for consumers, as it means a larger market for goods and services. This leads to lower prices and more choice of goods and services.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/2wyoE/2/

The World Trade Organisation uses the term “trade restrictive activity” for measures like the imposition of a tariff. “Trade facilitation” refers to the simplification of export and import processes, making it easier to trade across countries. “Trade remedies” refers to actions taken by states against certain imports that are hurting domestic industries.

For example, in 2016 the Australian Anti-Dumping Commission slapped duties on Italian tomatoes that were being sold in Australia for less than they sold in Italy.

The data show that tariffs have been declining in the G20 over the past few years, while countries have been easing the processes of exporting and importing. However there have been a lot of trade remedies, as countries try to protect their domestic industries.

But looking at data on non-tariff barriers to trade tells a very different story.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/6KdJA/1/

Until 2015 there was a huge increase in non-tariff measures, which then sharply declined. Since then not many measures have been removed. This shows that non-tariff barriers are currently the major mechanism for trade restrictions in the most developed economies.

As in the case of technical standards and regulations, non-tariff barriers can be used as a form of covert trade protectionism.

Technical standards and regulations can be quite legitimate and necessary for a range of reasons. They could take the form of a limit on what gases cars are allowed to emit, earthquake standards in regions prone to seismic activity, and even nutritional information on food and drinks.

But having too many different standards makes life difficult for companies that wish to access a market, as one product or service will need to comply with different standards in many countries.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/SC3Wl/2/

What has occurred in Australia echoes what has happened throughout the G20. There has been little activity recently in tariffs, but a significant use of non-tariff and technical barriers to trade.

This is a huge shift in Australia’s economic policy, which had until recently emphasised trade liberalisation as a recipe for growth.

According to the Australian Productivity Commission, trade restrictions directly raise the cost of both foreign and domestic goods and services, negatively impacting both Australian consumers and businesses.

President Donald Trump’s trade agenda aims to distance the United States from the World Trade Organisation, which was setup to remove barriers to international trade.

In response, companies in the United States are now filing a huge number of anti-dumping cases against foreign goods and services.

At first glance, Australia appears to be off the hook when it comes to Trump’s hardline approach. We already have a bilateral trade agreement with the United States, not to mention a US$28 billion trade deficit with the US.

![]() But the dangers of Trump’s trade doctrine could affect other countries and this disruption to global supply chains and financial security would eventually flow on to Australia.

But the dangers of Trump’s trade doctrine could affect other countries and this disruption to global supply chains and financial security would eventually flow on to Australia.

Giovanni Di Lieto, Lecturer, Bachelor of International Business, Monash Business School, Monash University and David Treisman, Lecturer in Economics, Bachelor of International Business, Monash Business School, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Joseph Camilleri, La Trobe University

Over the weekend, more than 120 countries adopted a treaty at a UN conference that prohibits the production, stockpiling, use or threatened use of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices. Australia was a notable absentee. So were the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons.

While the UN conference was taking a major step toward the elimination of nuclear weapons, the US and its allies – notably Japan, South Korea and Australia – were hoping to use the G20 summit in Hamburg to focus attention on the danger North Korea’s nuclear ambitions pose.

However, the declaration issued at the end of the G20 does not even mention the issue. We can now expect a UN Security Council resolution that condemns North Korea’s latest missile test and applies slightly tougher sanctions.

The glaring contradiction between the boycott of the nuclear ban negotiations and the preoccupation with the North Korean nuclear threat does not seem to have dawned on the US and its allies.

In North Korea’s eyes, its nuclear program is the only guarantee of regime survival.

North Korea’s apparently successful intercontinental ballistic missile test last week is widely seen, and portrayed by the regime itself, as part of a relentless drive to develop a reliable long-range nuclear weapon capable of striking the US.

The US responded to the latest test by declaring the policy of “strategic patience” is now over. In a speech delivered in Poland prior to the G20, US President Donald Trump warned he is considering “some pretty severe things” in response to North Korea’s “very, very bad behaviour”.

Yet America’s options are limited. In the first five months of his presidency, Trump’s strategy was to cajole China into taking a more confrontational stance with North Korea. But there are limits to what China is able or prepared to do.

Trump then intimated the use of tougher sanctions against North Korea, possible financial or trade sanctions against China for failing to do more, and even the direct use of military force.

However, resorting to these coercive tools is unlikely to have the desired result. History tells us harsh economic sanctions are often counter-productive. They impoverish economies, strengthen dictatorships, and drive dissent underground.

As for a military strike on North Korea, it could well lead the regime’s leader, Kim Jong-un, to launch a devastating strike against America’s allies, – notably Japan and South Korea. This might include the use of chemical, biological and possibly nuclear weapons. Such a turn of events may even drag China into the conflict.

More promising is the policy of strategic caution advocated by Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, which they reiterated in their separate meetings with Trump on the sidelines of the G20 summit.

Both Russia and China argue North Korea can be persuaded to halt nuclear and missile tests if, in return, the US and South Korea suspend their joint military exercises. This would be a prelude to the resumption of talks involving the US and North Korea that could lead to undertakings for all sides to refrain from the use of force or other aggressive measures.

This more pragmatic stance is close to the position of South Korean President Moon Jae-in, who argued in Hamburg that the focus should be kept on further sanctions and dialogue.

Nothing said at the G20 summit will resolve the North Korean crisis, for it is but a symptom of a deeper ailment.

The US and Russia, which between them account for 92% of the world’s nuclear weapons, are clearly intent on preserving and modernising their nuclear arsenals. They and other nuclear-armed countries have steadfastly resisted repeated calls for nuclear disarmament – even though Article 6 of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty requires them to do just that.

The nuclear weapons treaty that has just emerged is a direct response to the morally and legally culpable inaction of the nuclear-armed countries – something the G20 summit did not and could not do.

Put simply, the treaty is a comprehensive effort to bring the rule of law to bear on all aspects of the nuclear assault on the planet. It designates a nuclear-weapon-free world as “a global public good of the highest order”, on which depend:

… human survival, the environment, socioeconomic development, the global economy, food security and the health of current and future generations.

The treaty’s provisions are robust and thorough. In addition to prohibiting production, possession and deployment, each party to it undertakes never to test, transfer or receive from any recipient any nuclear weapons or explosive devices, and never to assist anyone or receive assistance from anyone to engage in any such activity.

Countries are further prohibited from ever allowing nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices to be stationed, installed, deployed or tested in their territory, or anywhere under their jurisdiction or control.

But there’s more to the treaty than this. It specifically acknowledges the unacceptable suffering and harm caused to the victims by nuclear weapons, as well as of those affected by the testing of nuclear weapons, in particular indigenous peoples.

The treaty also reinforces the legal obligation of relevant countries to provide appropriate remedies to the victims of nuclear testing, and effective repair of environmental damage.

Those who have been busy drafting and redrafting the treaty have taken great care to make room at a future date for those countries that have not participated in the negotiations – in particular nuclear-armed countries and their allies. A well-crafted set of procedures allows for the progressive, transparent and carefully verified dismantling of their nuclear activities.