Last week, a German vaccine advisory committee recommended the AstraZeneca vaccine only be used in 18-64-year-olds, citing a lack of data on the efficacy of the vaccine in people over 65.

Subsequently, the European regulator, the European Medicines Agency, conditionally approved the vaccine for anyone over 18.

What can we make of this? Should we be giving this vaccine to older people or not?

While we don’t yet have all the data we’d like, we don’t have reason to believe this vaccine won’t be at least somewhat effective in older adults. To exclude them from receiving it wouldn’t necessarily be the right approach.

The recommendation

STIKO, a German vaccine advisory committee that reports to the country’s government, was responsible for the draft recommendation which caused the stir. It released a similar final recommendation at the weekend.

While the German government may elect to follow STIKO’s advice or the European Medicines Agency’s guidelines, the latter’s approval carries significant weight. Equivalent to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia, this body decides which vaccines may legally be supplied in Europe.

The AstraZeneca vaccine has already received approvals, not singling out older age groups, from multiple international regulators, including those in the United Kingdom, India and Mexico.

Read more:

Germany may not give the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine to over-65s, but that doesn’t mean it won’t work

Why did STIKO make this recommendation?

STIKO’s advice is based on the fact it didn’t have enough data to definitively say whether the vaccine will work in older people — not because it won’t.

According to the data we have so far from AstraZeneca’s phase 3 trials, only two out of 660 people in the trial aged over 65 got sick with COVID-19. Two sick people isn’t enough for a strong statistical analysis.

AstraZeneca initially enrolled younger people in its trials, with older people enrolled only later. So data on older people in the original trials and another trial in the United States are still on the way.

Shutterstock

What do we know about the vaccine?

We have very good safety data for the AstraZeneca vaccine in older people. Older people actually have significantly lower levels of early side effects after vaccination. This makes sense, as older people’s immune systems don’t tend to react as strongly to vaccines, which would reduce many of these early side effects.

But the vaccine has been shown to induce strong immune responses in older people, which are likely to provide a degree of protection. The European Medicine Agency’s press release on their decision refers to a reasonable likelihood of protection based on this data.

So, just looking at immune responses, it’s reasonable to anticipate the AstraZeneca vaccine will be of some benefit, at least, to older people.

Read more:

Why we should prioritise older people when we get a COVID vaccine

What do we know from other vaccines?

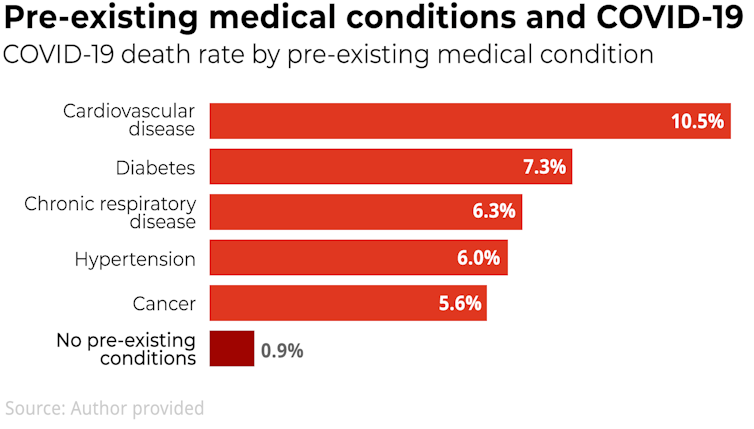

Often, vaccines aren’t as effective in older people as compared to younger people, because their immune responses can be less robust. For example, in 2010-2011 in the US, the flu vaccine was 60% effective in the general population, but only 38% effective in people over 65.

There’s more information on efficacy in older people for other COVID-19 vaccines. Notably, the Pfizer vaccine maintained efficacy of 93.7% for people over 55, compared to 95% overall. Accordingly, it would be reasonable to prioritise the Pfizer vaccine for older people.

But we’re beginning to see that vaccine supply and distribution can be unpredictable, with supply issues for Pfizer and AstraZeneca starting to affect vaccine rollout.

Importantly, all COVID-19 vaccines assessed so far, including the AstraZeneca vaccine, provide a high level of protection against severe disease and death across variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Shutterstock

Limiting access limits options for older people

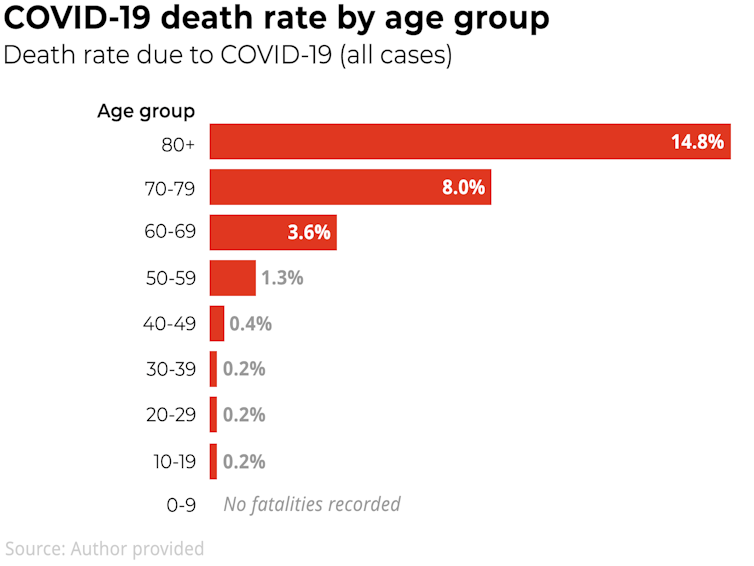

The question that advisory committees and regulators are weighing up is, should the AstraZeneca vaccine, or any vaccine, be recommended for older people if we know:

-

the vaccine has low risk of side effects

-

the vaccine has a fair but unconfirmed likelihood of providing some benefit

-

COVID-19 has a higher likelihood of severe disease and death in the demographic.

This is tricky to navigate and advice may differ across different vaccines and countries. For example, China is delaying vaccine rollout to older people while it waits for more data.

But conditional approval is a reasonable path to take. It allows for some uncertainty and maintains contact with the manufacturer. It also recognises that the likely benefit of giving older people any available vaccine could outweigh the hypothetical risk that it might not work in the midst of a crushing pandemic.

Read more:

The Oxford vaccine has unique advantages, as does Pfizer’s. Using both is Australia’s best strategy

In any case, approvals from regulators, such as the European Medicines Agency and the TGA, have the most impact — defining who the vaccine can be supplied to in a country.

If regulatory guidelines are kept open to all age groups above 18, it will facilitate access to vaccines for many people who could benefit from them. The next steps are distributing these vaccines, and educating and updating the public with the latest information as it comes to hand.

Crucially, we should support older people in vaccine decisions with two things; good information and easy access to an array of safe, protective vaccines.![]()

Kylie Quinn, Vice-Chancellor’s Research Fellow, School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.