Roberto Robanne/AP

David Oswald, RMIT University; Erica Kuligowski, RMIT University, and Kate Nguyen, RMIT UniversityThe collapse of the World Trade Center has been subject to intense public scrutiny over the 20 years since the centre’s twin towers were struck by aircraft hijacked by terrorists. Both collapsed within two hours of impact, prompting several investigations and spawning a variety of conspiracy theories.

Construction on the World Trade Center 1 (the North Tower) and World Trade Center 2 (the South Tower) began in the 1960s. They were constructed from steel and concrete, using a design that was groundbreaking at the time. Most high-rise buildings since have used a similar structure.

The investigatory reports into the events of September 11, 2001 were undertaken by the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

FEMA’s report was published in 2002. This was followed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s three-year investigation, funded by the US Federal Government and published in 2005.

Some conspiracy theorists seized on the fact the NIST investigation was funded by the federal government — believing the government itself had caused the twin towers’ collapse, or was aware it would happen and deliberately didn’t act.

While there have been critics of both reports (and the investigations behind them weren’t flawless) — their explanation for the buildings’ collapse is widely accepted. They conclude it was not caused by direct impact by the aircraft, or the use of explosives, but by fires that burned inside the buildings after impact.

BETH A. KEISER/EPA

Why did the towers collapse as they did?

Some have questioned why the buildings did not “topple over” after being struck side-on by aircraft. But the answer becomes clear once you consider the details.

Aircraft are made from lightweight materials, such as aluminium. If you compare the mass of an aircraft with that of a skyscraper more than 400 metres tall and built from steel and concrete, it makes sense the building would not topple over.

The towers would have been more than 1,000 times the mass of the aircraft, and designed to resist steady wind loads more than 30 times the aircrafts’ weight.

That said, the aircraft did dislodge fireproofing material within the towers, which was coated on the steel columns and on the steel floor trusses (underneath the concrete slab). The lack of fireproofing left the steel unprotected.

As such, the impact also structurally damaged the supporting steel columns. When a few columns become damaged, the load they carry is transferred to other columns. This is why both towers withstood the initial impacts and didn’t collapse immediately.

Read more:

9/11: the controversial story of the remains of the World Trade Center

Progressive collapse

This fact also spawned one of the most common conspiracy theories surrounding 9/11: that a bomb or explosives must have been detonated somewhere within the buildings.

These theories have developed from video footage showing the towers rapidly collapsing downwards some time after impact, similar to a controlled demolition. But it is possible for them to have collapsed this way without explosives.

It was fire that caused this. And this fire is believed to have come from the burning of remaining aircraft fuel.

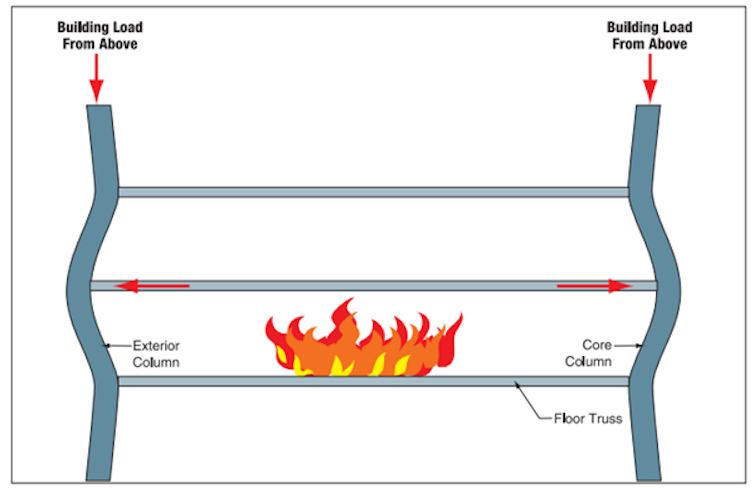

According to the FEMA report, fire within the buildings caused thermal expansion of the floors in a horizontal and outwards direction, pushing against the rigid steel columns, which then deflected to an extent but resisted further movement.

FEMA / https://www.fema.gov/pdf/library/fema403_ch2.pdf

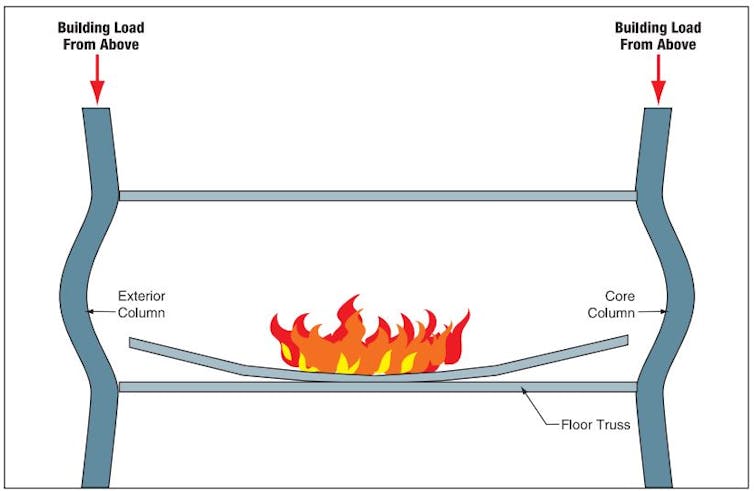

With the columns resisting movement there was nowhere else for the concrete floors to expand. This led to an increased buildup of stress in the sagging floors, until the floor framing and connections gave in.

The floors’ failure pulled the columns back inwards, eventually leading to them buckling, and the floors collapsing. The collapsing floors then fell on more floors below, leading to a progressive collapse.

FEMA / https://www.fema.gov/pdf/library/fema403_ch2.pdf

This explanation, documented in the official reports, is widely accepted by experts as the cause of the twin towers’ collapse. It is understood the South Tower collapsed sooner because it suffered more damage from the initial aircraft impact, which also dislodged more fireproofing material.

The debris from the collapse of the North Tower set at least ten floors alight in the nearby World Trade Center 7, or “Building 7”, which also collapsed about seven hours later.

While there are different theories regarding how the progressive collapse of Building 7 was initiated, there is consensus among investigators fire was the primary cause of failure.

Both official reports made a range of fire safety recommendations for other high-rise buildings, including to improve evacuation and emergency response. In 2007, the National Institute of Standards and Technology also published a best practice guide recommending risk-reducing solutions for progressive collapse.

What does this mean for high-rise buildings?

Before 9/11, progressive collapse was not well understood by engineers. The disaster highlighted the importance of having a “global view” of fire safety for a building, as opposed to focusing on individual elements.

There have since been changes to building codes and standards on improving the structural performance of buildings on fire, as well as opportunities to escape (such as added stairwell requirements).

At the same time, the collapse of the twin towers demonstrated the very real dangers of fire in high-rise buildings. In the decades since the World Trade Center was designed, buildings have become taller and more complex, as societies demand sustainable and cost-effective housing in large cities.

Some 86 of the current 100 tallest buildings in the world were built since 9/11. This has coincided with a significant increase in building façade fires globally, which have gone up sevenfold over the past three decades.

This increase can be partly attributed to the wide use of flammable cladding. It is marketed as an innovative, cost-effective and sustainable material, yet it has shown significant shortcomings in terms of fire safety, as witnessed in the 2017 Grenfell Disaster.

The Grenfell fire (and similar cladding fires) are proof fire safety in tall buildings is still a problem. And as structures get taller and more complex, with new and innovative designs and materials, questions around fire safety will only become more difficult to answer.

The events of 9/11 may have been challenging to foresee, but the fires that led to the towers’ collapse could have been better prepared for.

Read more:

Cladding fire risks have been known for years. Lives depend on acting now, with no more delays

![]()

David Oswald, Senior Lecturer in Construction, RMIT University; Erica Kuligowski, Vice-Chancellor’s Senior Research Fellow, RMIT University, and Kate Nguyen, Senior Lecturer, ARC DECRA Fellow and Victoria Fellow, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.