Shutterstock

Philip Hugenholtz, The University of Queensland and Soo Jen Low, The University of QueenslandResearch published today in Nature Microbiology has identified 54,118 species of virus living in the human gut — 92% of which were previously unknown.

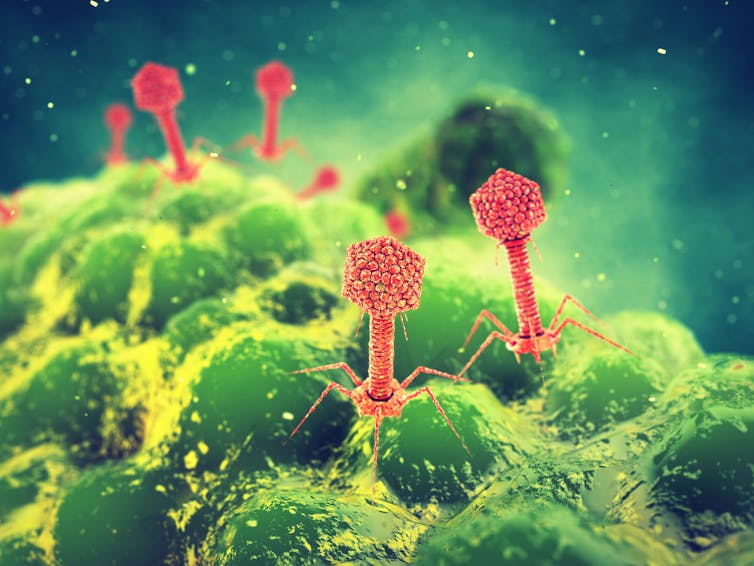

But as we and our colleagues from the Joint Genome Institute and Stanford University in California found, the great majority of these were bacteriophages, or “phages” for short. These viruses “eat” bacteria and can’t attack human cells.

When most of us think of viruses, we think of organisms that infect our cells with diseases such as mumps, measles or, more recently, COVID-19. However, there are a vast number of these microscopic parasites in our bodies — mostly in our gut — that target the microbes that live there.

Read more:

Know your bugs – a closer look at viruses, bacteria and parasites

Everybody poos (but not all poo is the same)

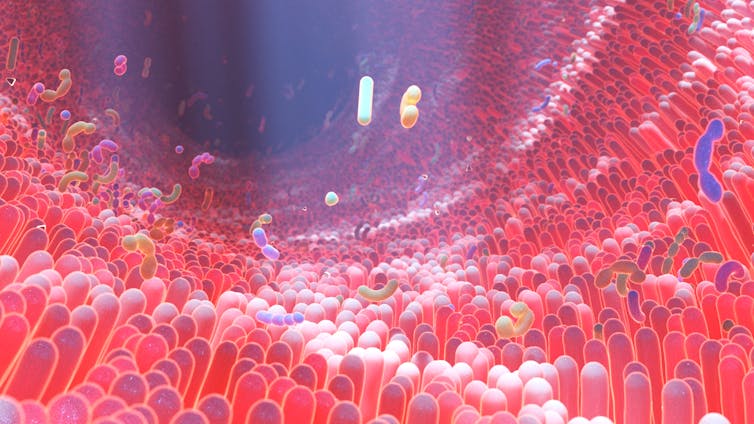

There has recently been much interest in the human gut microbiome: the collection of microorganisms that live in our gut.

Besides helping us digest our food, these microbes have many other important roles. They protect us against pathogenic bacteria, modulate our mental well-being, prime our immune system when we are children, and have an ongoing role in immune regulation into adulthood.

It’s fair to say the human gut is now the most well-studied microbial ecosystem on the planet. Yet more than 70% of the microbial species that live there have yet to be grown in the laboratory.

We know this because we can access the genetic blueprints of the gut microbiome via an approach known as metagenomics. This is a powerful technique whereby DNA is directly extracted from an environment and randomly sequenced, giving us a snapshot of what is present within and what it might be doing.

Shutterstock

Metagenomic studies have revealed how far we still have to go to catalogue and isolate all the microbial species in the human gut — and even further to go when it comes to viruses.

11,810 samples of poo

In our new research, we and our colleagues computationally mined viral sequences from 11,810 publicly available faecal metagenomes, taken from people in 24 different countries. We wanted to get an idea of the extent to which viruses have taken up residence in the human gut.

This effort resulted in the Metagenomic Gut Virus catalogue, the largest such resource to date. This catalogue comprises 189,680 viral genomes which represent more than 50,000 distinct viral species.

Remarkably (but perhaps predictably), more than 90% of these viral species are new to science. They collectively encode more than 450,000 distinct proteins — a huge reservoir of functional potential that may either be beneficial or detrimental to their microbial, and in turn human, hosts.

We also drilled down into subspecies of different viruses and found some showed striking geographical patterns across the 24 countries surveyed.

For example, a subspecies of the recently described and enigmatic crAssphage was prevalent in Asia, but was rare or absent in samples from Europe and North America. This may be due to localised expansion of this virus in specific human populations.

One of the most common functions we discovered in our molecular field trip were diversity-generating retroelements (DGRs). These are a class of genetic elements that mutate specific target genes in order to generate variation that can be beneficial to the host. In the case of DGRs in viruses, this may help in the ongoing evolutionary arms race with their bacterial hosts.

Intriguingly, we found one-third of the most common virally-encoded proteins have unknown functions, including more than 11,000 genes distantly related to “beta-lactamases”, which enable resistance to antibiotics such as penicillin.

Linking gut viruses to their microbial hosts

Having identified the phages, our next task was to link them to their microbial hosts. CRISPRs, best known for their many applications in gene editing, are bacterial immune systems that “remember” past viral infections and prevent them from happening again.

They do this by copying and storing fragments of the invading virus into their own genomes, which can then be used to specifically target and destroy the virus in future encounters.

We used this record of past attacks to link many of the viral sequences to their hosts in the gut ecosystem. Unsurprisingly, highly abundant viral species were linked to highly abundant bacterial species in the gut, mostly belonging to the bacterial phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidota.

So what can we do with all of this new information? One promising application of an inventory of gut viruses and their hosts is phage therapy. Phage therapy is an old concept predating antibiotics, in which viruses are used to selectively target bacterial pathogens in order to treat infections.

There has been discussion of potentially customising people’s gut microbiomes using dietary interventions, probiotics, prebiotics or even “transpoosions” (faecal microbiota transplants), to improve an individual’s health.

Phage therapy may be a useful addition to this objective, by adding species or even subspecies-level precision to microbiome manipulation. For example, the bacterial pathogen Clostridioides difficile (or Cdiff for short) is a leading cause of hospital-acquired diarrhoea that could be specifically targeted by phages.

More subtle manipulation of non-pathogenic bacterial populations in the gut may be achievable through phage therapy. A complete compendium of gut viruses is a useful first step for such applied goals.

It’s worth noting, however, that projections from our data suggest we’ve only investigated a fraction of the total gut viral diversity. So we’ve still got a long way to go.

Read more:

How do viruses mutate and jump species? And why are ‘spillovers’ becoming more common?

![]()

Philip Hugenholtz, Professor of Microbiology, School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, The University of Queensland and Soo Jen Low, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.