Jacquelyn Martin/AP

Gorana Grgic, University of Sydney

Throughout the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, Joe Biden spent significant time reassuring American allies around the world that Trump’s America is not “who we are” and pledging “we’ll be back”.

Now that he’s the president-elect, those who were most worried about another four years of “America First” foreign policy are no doubt breathing a sigh of relief.

Much has been written about a Biden presidency being focused on restoration, or as David Graham of The Atlantic put it,

returning the United States to its rightful place before (as he sees it) the current president came onto the scene and trashed the joint.

LINTAO ZHANG / POOL /EPA

The old world order doesn’t exist anymore

This idea has revolved around restoring the post-1945 liberal international order – a term subject to a lot of academic contention. The US played a central role in creating and leading the order around key institutions such as the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organisation, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the like.

However, there is now no shortage of evidence that many of these institutions have come under extreme strain in recent years and have been unable respond to the challenges of the 21st century geopolitics.

For one, the US no longer wields the relative economic power or influence it had in the middle of last century. There are also increasingly vocal critics in the US — led by Trump — who question America’s foreign commitments.

Hau Dinh/AP

Moreover, nations themselves are no longer the only important actors in the international system. Terror groups like the Islamic State now have the ability to threaten global security, while corporations like Alphabet, Amazon, Apple and Facebook have such economic power, their combined revenue would qualify them for the G20.

Equally, the so-called liberal international order was built on the idea that a growing number of democracies would be willing to work within institutions like the UN, IMF and WTO and act in ways that would make everyone in the system better off.

Clearly, that has not been the case for the past 15 years as democracies around the world slowly eroded, from European Union states like Hungary and Poland to Brazil to the US.

Read more:

Biden wins – experts on what it means for race relations, US foreign policy and the Supreme Court

Biden can’t fix everything at once

Trump’s 2016 election seemed to have been the final nail in the coffin for the idea of a truly liberal international order with the US as a benevolent leader.

From his first days in office, Trump was on a mission to roll back US commitments to myriad organisations, deals and relationships around the world. Most significantly, this included questioning commitments to its closest allies in Europe, Asia and elsewhere that had been unwavering for generations.

Francisco Seco/AP

Biden takes over at a precarious time. The world is more unstable than it has been in decades and the US image has been severely damaged by the actions and rhetoric of his predecessor.

There is no naivety on Biden’s part that he will be able to fix everything that was broken along the way. After all, many of these challenges predated Trump and are merely a reflection of a changing world.

Furthermore, Biden will have many pressing domestic issues that will demand his immediate attention — first and foremost addressing the greatest public health and economic crisis in a century.

We are also likely to see growing pressure for Biden to pursue a more progressive climate policy and a better-managed industrial policy, though he’ll be greatly constrained in what he can do if the Republicans maintain control of the Senate.

All of this will limit both his bandwidth and appetite for an overly ambitious foreign policy agenda.

Read more:

What would a Biden presidency mean for Australia?

Rejoining the world, with managed expectations

Given this, Biden’s presidency should be approached with managed expectations. Unlike President Barack Obama, he did not campaign on lofty promises of change. He ran on being the opposite of Trump and, as such, being better able to understand the intricacies of foreign policy.

This will mean a swift return to multilateralism and rejoining the deals and organisations Trump abandoned, from the Paris climate agreement and Iran nuclear deal to the the World Trade Organisation and World Health Organisation.

Given these moves by Trump required no congressional input, Biden will be able to return to Obama-era policies in a relatively straightforward fashion through executive action.

However, this didn’t produce the expected “blue wave” and national repudiation of Trumpism, so it remains to be seen whether friends and foes alike can be convinced the past four years were an aberration. In essence, how good can America’s word be moving forward?

Biden’s campaign put a great emphasis on strengthening America’s existing alliances and forging new ones to maintain what he frequently refers to as “a free world”.

This will involve a substantial change from the way Trump managed US alliances, nurturing relationships with authoritarian leaders in the Middle East, for example, and some of the least liberal eastern European states.

This shift will benefit America’s traditional allies in western Europe the most. However, these countries are more determined than ever to stop depending on the whims of the Electoral College to decide their security. Instead, they are strengthening their own defence capabilities.

‘America First’ finished second

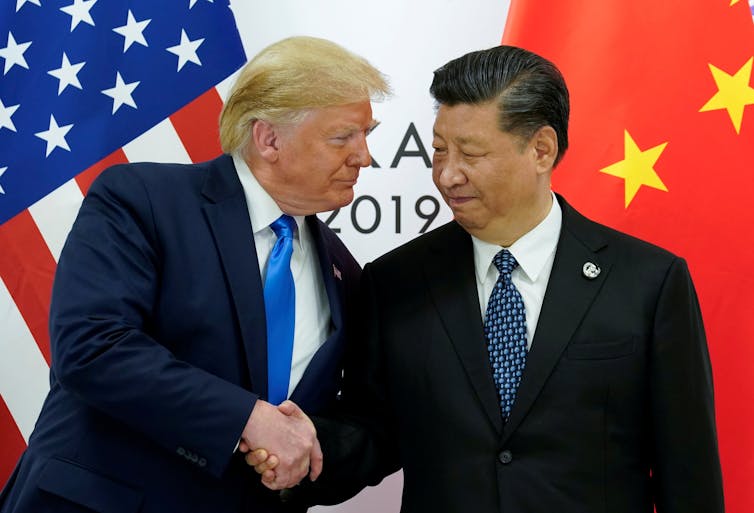

Lastly, on the greatest geopolitical question of our time, there is no doubt the US will continue its competition with China in the coming years, no matter who is president.

Yet, there are still plenty of questions around how Biden will handle this relationship. His campaign adopted a much more hawkish stance toward China compared to the Obama administration, which reflects a growing bipartisan consensus the US must get tougher with Beijing.

Read more:

Trump took a sledgehammer to US-China relations. This won’t be an easy fix, even if Biden wins

At the same time, there is significant debate about how far his administration should push Beijing on issues ranging from technological competition to human rights, particularly given Biden has said the US needs to find a way to cooperate with China on other pressing issues, such as climate change, global health and arms control.

America might be coming back under Biden, but this is not the same world or the same country it once was. So, while the restoration of the US will be challenging, one thing is certain: “America First” finished second.![]()

Gorana Grgic, Lecturer in US Politics and Foreign Policy, US Studies Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.