Shutterstock

Kalinda Griffiths, UNSWOn Sunday, New South Wales saw four more deaths from COVID-19. One of them was a man from Dubbo who was in his 50s and unvaccinated. It was the first COVID-19 death of a First Nations person in Australia.

Aboriginal communities in remote areas have been pleading with the government for help with medical resourcing and food for families. It was recently found there were pleas for protection against COVID in Wilcannia, with Aboriginal health organisation Maari Ma Aboriginal Health contacting Ken Wyatt about this back in March last year.

There has been some progress in the nation’s vaccination rates with a little over 32% of the eligible population over the age of 12 now vaccinated. However, the second wave of COVID-19 in New South Wales highlights concerns for the unvaccinated and those with multiple risk factors. This includes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

New South Wales is now in day 76 of their most recent outbreak with cases reaching over 20,000.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were identified as a priority group early in the vaccine rollout, yet they still have lower vaccination rates than the NSW population.

Almost 12% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are fully vaccinated in NSW compared to almost 30% of the non-Indigenous population.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at risk

It’s well known Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience higher rates of disease than non-Indigenous people. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in New South Wales experience two or more health conditions at a rate that is over two and half times greater than non-Indigenous people.

In addition, there is increased risk of spread in families, as larger family groups often live together in regional and remote communities.

These risks, along with extreme yet ignored service gaps in regional and remote areas, mean our Indigenous community is facing severe risk of death and disease from the COVID-19 pandemic.

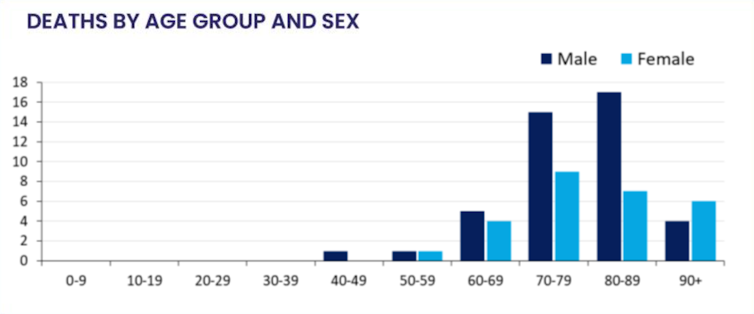

Children and young people under the age of 20 account for a little over 20% of Australia’s case numbers, with all children aged 12 to 15 now recommended to get the Pfizer vaccine.

Pre-existing conditions such as asthma, gastrointestinal disease, diabetes/prediabetes, as well as children who are immunocompromised and preterm, have been found to be predictors of severe COVID-19 disease.

This is of great concern to Aboriginal communities, considering Aboriginal children are up to two times more likely to be hospitalised for respiratory conditions than non-Indigenous children.

Read more:

The COVID-19 crisis in western NSW Aboriginal communities is a nightmare realised

We need better data

The gaps in COVID-19 publicly available data are concerning, especially data specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

There is currently no information on vaccination rates for children over the age of 12 in out-of-home care. In 2018 there were 45,800 children in out-of-home care. About 40% of these children are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

There is also little to no data available on the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people tested for COVID, as well as issues with the accuracy of Indigenous status in the reporting of the case numbers.

Despite the daily high case numbers, this week the New South Wales government announced restrictions in the state will be relaxed across selected local government areas for those people who are fully vaccinated.

While the risk for those people who are vaccinated is relatively low, greater activity could still increase the spread of COVID-19 across the state, putting people in Aboriginal communities at greater risk.

Knowing exactly who is vaccinated and who is at greatest risk will be of the utmost importance as restrictions start to ease.

How the public can help

The increasing case numbers and resultant lockdowns across NSW local government areas have seen Aboriginal communities having limited access to health care and basic necessities due to limitations in the supply of regional and remote supermarkets. A number of First Nations people have rallied together to support their communities.

This has included pages that have been set up for:

- emergency food packs across western NSW

- support for Wilcannia community

- fresh fruit and veggies in Wilcannia

- a volunteer group to assist in coordinating water and food support in Wilcannia nd provides opportunities for people to volunteer.

- an interstate fundraiser from Lullas Children and Family Centre to supply Aboriginal kids with educational toys, games and other items

People can donate or contact the volunteer group to get involved.

Where to next?

As the Delta variant makes its way across Australia, all people need access to vaccines. This means increasing government resources and health system efforts in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities as well as ensuring all Indigenous people have multiple access points to the vaccines.

This could include door-to-door vaccinations in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, pop-up vaccination clinics in regional and remote local government areas as well as school-based vaccinations.

With the expected mRNA vaccine supplies to be sufficient for the entire Australian population in the coming months, the biggest next step is ensuring their distribution is prioritised to those who need it the most.

This requires moving beyond the rhetoric and supporting health services, particularly Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, to do the work.![]()

Kalinda Griffiths, Scientia lecturer, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.