Lara Herrero, Griffith UniversityDelta was recognised as a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in May 2021 and has proved extremely difficult to control in unvaccinated populations.

Delta has managed to out-compete other variants, including Alpha. Variants are classified as “of concern” because they’re either more contagious than the original, cause more hospitalisations and deaths, or are better at evading vaccines and therapies. Or all of the above.

So how does Delta fare on these measures? And what have we learnt since Delta was first listed as a variant of concern?

Read more:

Is Delta defeating us? Here’s why the variant makes contact tracing so much harder

How contagious is Delta?

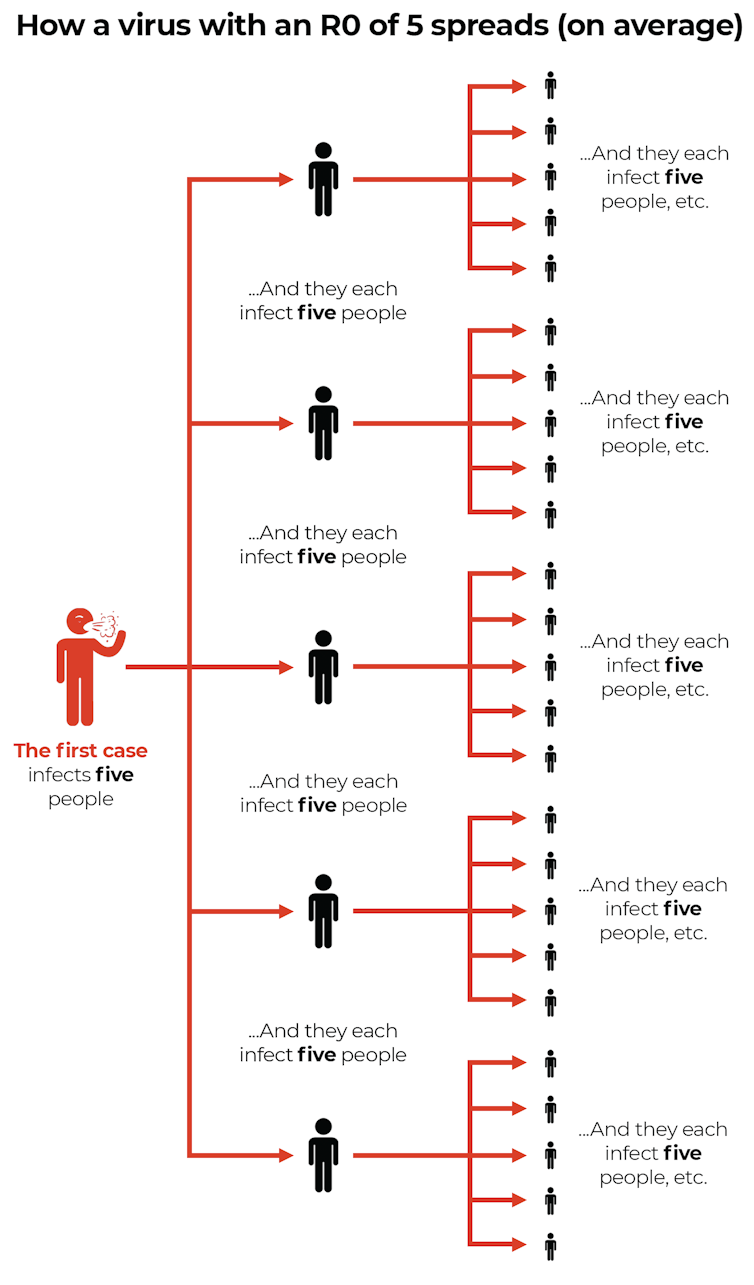

The R0 tells us how many other people, on average, one infected person will pass the virus on to.

Delta has an R0 of 5-8, meaning one infected person passes it onto five to eight others, on average.

This compares with an R0 of 1.5-3 for the original strain.

So Delta is twice to five times as contagious as the virus that circulated in 2020.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

What happens when you’re exposed to Delta?

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted through droplets an infected person releases when they breathe, cough or sneeze.

In some circumstances, transmission also occurs when a person touches a contaminated object, then touches their face.

Shutterstock

Once SARS-CoV-2 enters your body – usually through your nose or mouth – it starts to replicate.

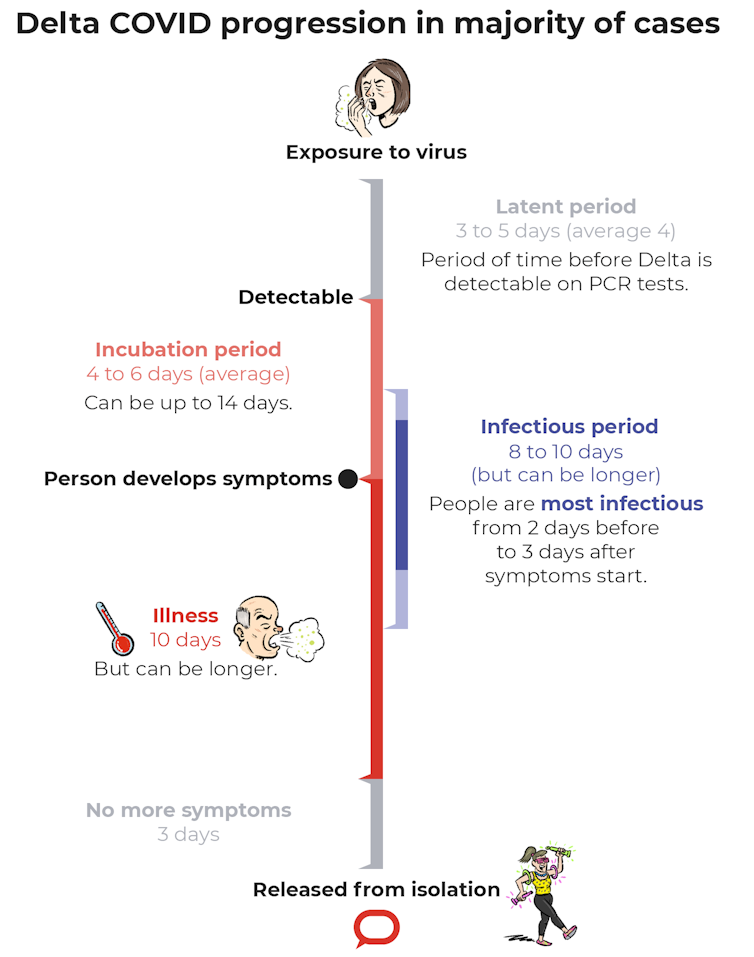

The period from exposure to the virus being detectable by a PCR test is called the latent period. For Delta, one study suggests this is an average of four days (with a range of three to five days).

That’s two days faster than the original strain, which took roughly six days (with a range of five to eight days).

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The virus then continues to replicate. Although often there are no symptoms yet, the person has become infectious.

People with COVID-19 appear to be most infectious two days before to three days after symptoms start, though it’s unclear whether this differs with Delta.

The time from virus exposure to symptoms is called the incubation period. But there is often a gap between when a person becomes infectious to others to when they show symptoms.

As the virus replicates, the viral load increases. For Delta, the viral load is up to roughly 1,200 times higher than the original strain.

With faster replication and higher viral loads it is easy to see why Delta is challenging contact tracers and spreading so rapidly.

What are the possible complications?

Like the original strain, the Delta variant can affect many of the body’s organs including the lungs, heart and kidneys.

Complications include blood clots, which at their most severe can result in strokes or heart attacks.

Around 10-30% of people with COVID-19 will experience prolonged symptoms, known as long COVID, which can last for months and cause significant impairment, including in people who were previously well.

Shutterstock

Longer-lasting symptoms can include fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, headaches, brain fog, muscle aches, sleep disturbance, depression and the loss of smell and taste.

Is it more deadly?

Evidence the Delta variant makes people sicker than the original virus is growing.

Preliminary studies from Canada and Singapore found people infected with Delta were more likely to require hospitalisation and were at greater risk of dying than those with the original virus.

In the Canadian study, Delta resulted in a 6.1% chance of hospitalisation and a 1.6% chance of ICU admission. This compared with other variants of concern which landed 5.4% of people in hospital and 1.2% in intensive care.

In the Singapore study, patients with Delta had a 49% chance of developing pneumonia and a 28% chance of needing extra oxygen. This compared with a 38% chance of developing pneumonia and 11% needing oxygen with the original strain.

Similarly, a published study from Scotland found Delta doubled the risk of hospitalisation compared to the Alpha variant.

Shutterstock

How do the vaccines stack up against Delta?

So far, the data show a complete course of the Pfizer, AstraZeneca or Moderna vaccine reduces your chance of severe disease (requiring hospitalisation) by more than 85%.

While protection is lower for Delta than the original strain, studies show good coverage for all vaccines after two doses.

Can you still get COVID after being vaccinated?

Yes. Breakthrough infection occurs when a vaccinated person tests positive for SARS-Cov-2, regardless of whether they have symptoms.

Breakthrough infection appears more common with Delta than the original strains.

Most symptoms of breakthrough infection are mild and don’t last as long.

It’s also possible to get COVID twice, though this isn’t common.

How likely are you to die from COVID-19?

In Australia, over the life of the pandemic, 1.4% of people with COVID-19 have died from it, compared with 1.6% in the United States and 1.8% in the United Kingdom.

Data from the United States shows people who were vaccinated were ten times less likely than those who weren’t to die from the virus.

The Delta variant is currently proving to be a challenge to control on a global scale, but with full vaccination and maintaining our social distancing practices, we reduce the spread.

Lara Herrero, Research Leader in Virology and Infectious Disease, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.