Mark Hanly, UNSW; C Raina MacIntyre, UNSW; Ian Caterson, University of Sydney; Louisa Jorm, UNSW; Oisin Fitzgerald, UNSW, and Timothy Churches, UNSWAustralia’s vaccine rollout is due to be reset after the news last night the AstraZeneca vaccine would not be recommended for people under 50. Instead, this age group will be offered the Pfizer vaccine, with the federal government today announcing it had secured an additional 20 million doses.

Although details of the redesigned rollout have yet to be released, our new modelling, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, shows how this might work under a range of scenarios, including the logistical requirements of different vaccines, and different vaccination venues.

Once a steady stream of locally manufactured AstraZeneca vaccine is available in Australia, the bottleneck in the vaccine rollout will shift from supply to administration. That’s when expanded GP vaccination clinics and mass vaccination hubs will be needed to deliver these jabs to nine million people over 50 in phases 1b and 2a of the rollout.

Read more:

New setback for vaccine rollout, with AstraZeneca not advised for people under 50

Here’s what we did and what we found

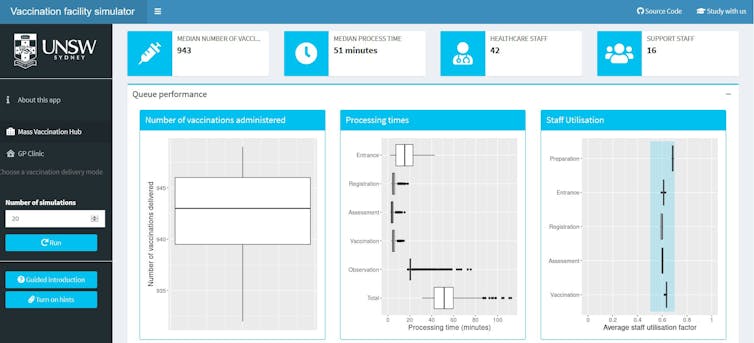

We used mathematical simulations of waiting in line, known as stochastic queue network models, to model the process of running a vaccination clinic.

Queue models allow us to assess the daily vaccination capacity for different venues, taking into account available staff numbers and estimated times to complete each stage of the vaccination process.

The two key venues we looked at were mass vaccination hubs — which could be large venues such as halls, parks or stadiums — and GP clinics.

Mass vaccination hubs and GP clinics lay out their vaccine clinics differently. Hubs with larger premises and more staff can adopt an assembly line approach to vaccination. They can divide the tasks of registration, clinical assessment, vaccine preparation and administration across a series of stations. Smaller clinics are likely to have fewer people available, each performing multiple tasks. We developed two distinct models to reflect these different set-ups.

Read more:

Australia urgently needs mass COVID vaccination hubs. But we need more vaccines first

We used these models to estimate how many vaccines could be delivered in an eight-hour clinic based on a range of staffing levels, within an average overall waiting time of under an hour.

We estimate a small general practice could administer 100 doses, rising to 300 doses for a large practice. Mass vaccination clinics could deliver 500-1,400 doses in the same period, depending on staff numbers.

We also used our models to test how clinics would perform under service pressures, including increased vaccine availability and staff shortages.

For both delivery modes, sites with more staff were better able to keep waiting times under control as system pressures increased. Unsurprisingly, mass vaccination hubs were more robust compared to GP clinics.

Read more:

4 ways Australia’s COVID vaccine rollout has been bungled

We can test different scenarios

Our models rely on subjective assumptions about the time needed to complete different stages in the vaccination process. In reality, these timings will vary in different contexts.

For instance, the Pfizer vaccine takes longer to prepare than the AstraZeneca vaccine. Our models can account for this by increasing the expected preparation time and seeing how many extra staff would be needed to run a vaccine clinic with the same number of appointments. When the Novavax or other vaccines come on board, we can re-run the model with updated preparation times.

In fact, we have developed an an app that allows anyone to re-run our simulations based on their own assumptions about service times, appointment schedules and staffing availability.

Author supplied/UNSW

This can support policymakers, individual GPs and community pharmacies to plan vaccination delivery, as the quantity and type of available vaccine varies throughout the rollout.

However, there are some aspects of vaccine rollout our models do not account for. This includes essential support staff, such as administrators, cleaners and marshals.

Neither do our models address the logistics of distributing vaccines to vaccination centres, which is a separate challenge.

Read more:

How the Pfizer COVID vaccine gets from the freezer into your arm

One isn’t ‘better’ than the other. We need both

Our models suggest mass vaccination hubs and GP clinics are equally efficient in terms of the number of doses delivered per staff member. This supports distribution through both modes, provided GPs are enabled to vaccinate at their peak capacity.

These two approaches offer distinct advantages. Older people or clinically vulnerable patients may benefit from attending their local GP, who will be familiar with their medical history.

Younger males, busy working people and marginalised populations are less likely to have a regular GP and may be easier to reach through mass vaccination hubs. The rollout of phase 2 to adults under 50 may require expansion of the hubs, as not all GPs may be able to store the Pfizer vaccine.

A diverse profile of vaccination sites, drawing on the benefits of different distribution modes, will help maximise the daily vaccination rate and vaccinate the Australian population against COVID-19 as quickly as possible.![]()

Mark Hanly, Research Fellow, UNSW; C Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Global Biosecurity, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Head, Biosecurity Program, Kirby Institute, UNSW; Ian Caterson, Medical Lead, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital COVID Vaccination Clinic, Sydney Local Health District, Boden Professor of Human Nutrition, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney; Louisa Jorm, Director, Centre for Big Data Research in Health, UNSW; Oisin Fitzgerald, PhD Candidate, UNSW, and Timothy Churches, Senior Research Fellow, South Western Sydney Clinical School, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.