JAMES ROSS/AAP

Rick Sarre, University of South Australia and Joe McIntyre, University of South Australia

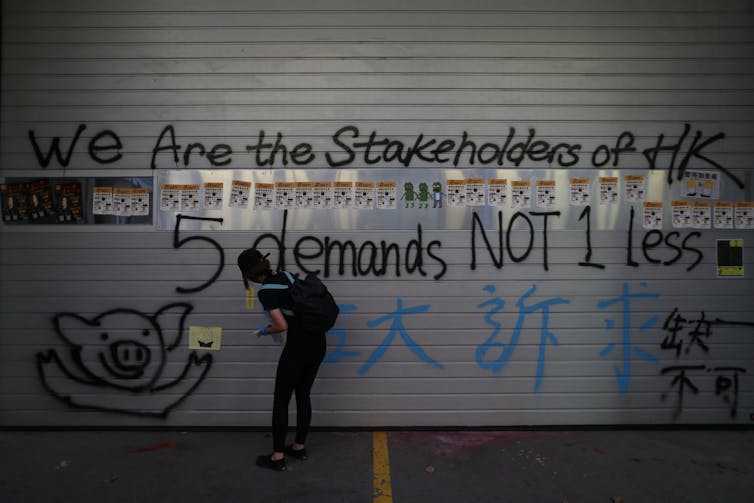

Lockdown has been particularly hard in Victoria and some dissent against restrictions is to be expected.

While it might be easy to dismiss the anti-lockdown protesters by calling them selfish or deluded, we should not lose sight of just how far beyond our normal expectations of civic responsibility the last six months have taken us.

By and large, most Victorians have been exceptionally responsible and stoic. And while police enforcement has been problematic at times, regulatory requirements often unclear and emergency powers unlike anything we’ve seen in a century, the vast majority of Victorians, indeed all Australians, continue to trust the actions of governments are reasonable and constitutionally valid.

Not everyone agrees, however, with this proposition.

In recent weeks, there has been an increase in social media traffic asserting the lockdown measures — and indeed our legal institutions themselves — are unlawful and unconstitutional.

These arguments — some inspired by the “sovereign citizen” movement — are also showing up in online forums, the courts and the streets.

Some of these protesters argue, for example, that all laws passed since November 18, 1975, in Victoria are invalid because Queen Elizabeth did not personally sign off on the new state Constitution.

Another argument is the Victorian courts have no vested authority because the oath each judge takes is not addressed to the queen using her proper title, or at all.

These are strong accusations. But are they true?

ERIK ANDERSON/AAP

How our system of government works

To address this question, it is important to start with some general principles of law.

In Australia, we are governed by a blend of constitutional styles: a federation of states (like the US) but in a Westminster setting (like the United Kingdom).

The central document that sets out our political system is the Commonwealth Constitution, which is augmented by state constitutions.

Read more:

Why QAnon is attracting so many followers in Australia — and how it can be countered

The Constitution gives federal parliament in Canberra power over a range of specific matters (defence, customs, immigration), with the rest largely left to the states (including law enforcement).

However, the federal government has most of the money, and can therefore exert influence over policies dealing with education, health and the environment, all of which fall outside of its lawmaking mandate.

SCOTT BARBOUR/AAP

We have very few constitutionally protected legal rights. Fortunately, we have a rich tradition of legal conventions and common law principles that underpin our democratic processes.

Most people, however, do not understand these complexities. And that leaves many angry and frustrated.

The rise of the “sovereign citizen” movement — which purports to reclaim the law for the individual — is entirely understandable. But this does not mean that its proponents are correct.

Conspiracy theorists claims debunked

Let’s look at some of the arguments of those claiming Australia is in a constitutional crisis.

These conspiracy theorists claim, for instance, that every oath of office not using the full title “Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom & Northern Ireland and the Commonwealth” is invalid. As a result, our judges, governors and police commissioners are all impostors.

This proposition is nonsensical. One accepted shortened form in oaths, “Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, her heirs and successors”, is based on the schedule to the Constitution. Another form, “the Queen of Australia”, is regularly used by the High Court.

Indeed, some jurisdictions, including Victoria, have legitimately removed references to the queen from their legal forms entirely, which parliamentary sovereignty allows them to do. These changes do not have to be approved by referenda.

ERIK ANDERSON/AAP

Also, according to conspiracy theorists, Victoria’s courts are invalid because the attorney general did not have a mandate from electors to set up the court services in 2014, as this plan was not in the party’s pre-election platform.

This claim is also unfounded. In a representative democracy, we elect politicians to make decisions for us — we do not vote directly on specific legislative actions.

Another argument asserts the 1975 Victorian Constitution is invalid because the queen did not sign the bill that created it, only the Victorian governor did. According to one theory, the queen, as head of state, was required to put her signature on it.

But according to the High Court, this is a specious claim.

In 2013, in the case of Rutledge v Victoria, Justice Kenneth Hayne addressed this very argument. He found the bill did not need an actual signature. Instead, according to longstanding practice, the queen merely had to provide “royal assent”, in other words, a royal nod.

Better civics education is clearly needed

These conspiracy arguments have been routinely shown to be without legal foundation.

But the rise of “constitutional crisis” arguments highlights the shortcomings of our civics education in Australia to adequately explain governmental structures, legal principles and parliamentary conventions. For most people, the law remains mysterious and inaccessible.

While we have a system that makes it compulsory to vote, we do not equip Australians to understand how the legal system operates, how the myriad of accountability structures work and how citizens can engage with them.

Despite laudable efforts to correct this, the lack of functional knowledge remains widespread. And the vacuum in legal knowledge is quickly filled with social media mischief-making.

Underlying the conspiracy theories is the idea there is an alternative legal truth, the revelation of which will liberate the oppressed from the constraints of authoritarian governments. While these claims are without any legal merit, their growing prevalence should ring alarm bells about the parlous state of civics education in this country.

We have learned during this health emergency the value of placing our trust in medical experts. Some people, however, are reluctant to extend that trust to other experts, including legal experts.

To some extent this is appropriate. Our political system belongs to us, and we need to question and test it at every opportunity.

However, legal quackery is as dangerous as the medical variety. In a time of crisis, such as in a pandemic, it is essential for us to have open and informed debate about the best way through it, based upon fact, not fiction.

The conspiracy theorists are doing themselves a disservice by throwing their considerable energies into irrelevancies rather than engaging in key political debates. While enticing to some, their pronouncements are the last thing we need right now.![]()

Rick Sarre, Emeritus Professor of Law and Criminal Justice, University of South Australia and Joe McIntyre, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.