CSIRO, Author provided

Katherine Wynn, CSIRO; James Deverell, CSIRO; Max Temminghoff, CSIRO, and Mingji Liu, CSIRO

Over the next few years, science and technology will have a vital role in supporting Australia’s economy as it strives to recover from the coronavirus pandemic.

At Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, we’ve identified opportunities that can help businesses drive economic recovery.

We examined how the pandemic has created or intensified opportunities for economic growth across six sectors benefiting from science and technology. These are food and agribusiness, energy, health, mineral resources, digital and manufacturing.

Advanced healthcare

While some aspects of Australian healthcare are currently digitised, system-wide digital health integration could improve the quality of care and save money.

Doctors caring for patients with chronic diseases or complex conditions could digitally coordinate care routines. This could streamline patient care by avoiding consultation double-ups and providing a more holistic view of patient health.

We also see potential for more efficient healthcare delivery through medical diagnostic tests that are more portable and non-invasive. Such tests, supported by artificial intelligence and smart data storage approaches, would allow faster disease detection and monitoring.

There’s also opportunity for developing specialised components such as 3D-printed prosthetics, dental and bone implants.

Green energy

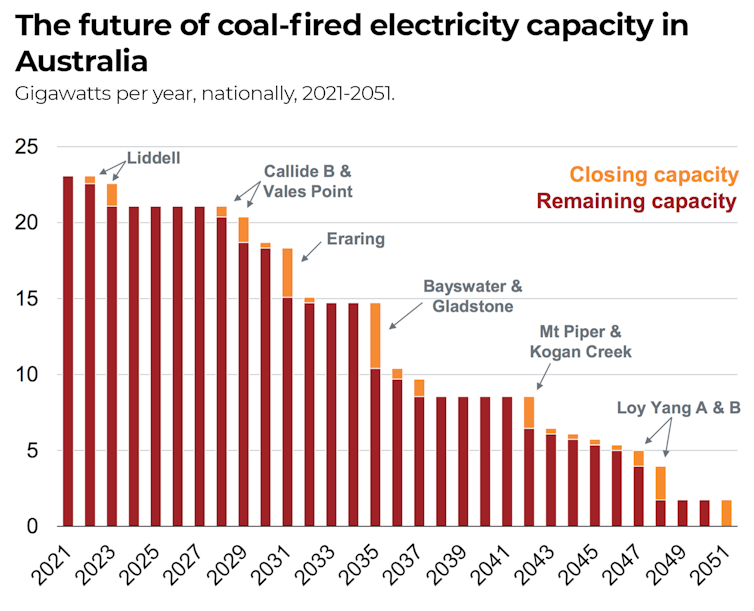

Despite a short-term plateau in energy consumption caused by COVID-19 globally, the demand for energy will continue to grow.

Through clean energy exports and energy initiatives aligned with decarbonisation goals, Australia can help meet global energy demands. Energy-efficient technologies offer immediate reduced energy costs, reduced carbon emissions and less demand on the energy grid. They also create local jobs.

Read more:

It might sound ‘batshit insane’ but Australia could soon export sunshine to Asia via a 3,800km cable

Innovating with food and agribusiness

The food and agribusiness sector is a prominent contributor to Australia’s economy and supports regional and rural prosperity.

Global population growth is driving an increased demand for protein. At the same time, consumers want more products that are sustainable and ethically sourced.

Australia could earn revenue from the local production and export of more sustainable proteins. This might include plant-based proteins such as pea and lupins, or aquaculture products such as farmed prawns and seaweed.

We could also offer more high-value health and well-being foods. Examples include fortified foods and products free from gluten, lactose and other allergens.

Automating minerals processes

Even before COVID-19 struck, the mineral resources sector was facing rising costs and declining ore grades. It’s also dealing with climate change impacts such as droughts, bushfires, floods, and social pressures to reduce environmental harm.

Several innovative solutions could help make the sector more productive and sustainable. For instance, increasing automation and remote mining (which Australia already excels in) could achieve improved safety for workers, more productivity and business continuity.

Also, investing in advanced technologies that can generate higher quality data on mineral character and composition could improve yields and minimise environmental harm.

High-tech manufacturing

COVID-19 has escalated concerns around Australia’s supply chain fragility – take the toilet paper shortages earlier in the pandemic. Expanding local manufacturing efforts could create jobs and increase Australia’s earning potential.

This is especially true for mineral processing and manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, food and beverages, space technology and defence. Our local manufacturing will need to adapt quickly to changes in supply needs, ideally through the use of advanced designs and technology.

Digital solutions

In April and May this year, Australian businesses made huge strides in adopting consumer and business digital technologies. One study estimated five years’ worth of progress occurred in those eight weeks. Hundreds of thousands of businesses moved their work online.

Over the next two years, Australian businesses could become more efficient and adaptable by further monetising the data they already collect. For example, applying mobile sensors, robotics and machine learning techniques could help us make better resource decisions in agriculture.

Similarly, businesses could share more data throughout the supply chain, including with customers and competitors. For instance, increased data sharing among renewable energy providers and customers could improve the monitoring, forecasting and reliability of energy supply.

Making the right plans and investments now will determine Australia’s recovery and resilience in the future.![]()

Katherine Wynn, Lead Economist, CSIRO Futures, CSIRO; James Deverell, Director, CSIRO Futures, CSIRO; Max Temminghoff, Senior Consultant, CSIRO, and Mingji Liu, Senior Economic Consultant, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.