Tag Archives: financial

Cashless payment is booming, thanks to coronavirus. So is financial surveillance

Jack Parkin, Western Sydney University

A banknote has been sitting in my wallet for six months now. As time ticks on, it burns an ever greater hole in my pocket.

At first I felt uneasy spending it, following COVID-19 warnings to pay more attention to hand hygiene and the surfaces we all touch on a daily basis.

Now I have less and less opportunity to do so. While the World Health Organisation has never advised against using cash, more and more businesses are displaying signs that read “We Only Accept Contactless Payment” next to their registers.

A recent global poll conducted by MasterCard – a company with reason to favour card-based payments – found 82% of its users see contactless payments as cleaner than cash.

Online shopping is booming too. Amazon’s value alone has risen by 570 billion US dollars this year.

But while electronic payment may reduce our exposure to germs, it also shows banks, vendors and payment platforms what we do with our money. Social media is awash with posts condemning the forced use of contactless payment for fear of overseers eyeballing spending. Some people are even boycotting stores that won’t accept cash.

The growth of digital transactions exposes yet another aspect of our personal life to, what the social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff has called, “surveillance capitalism”. Financial data is now a valuable raw material that can be bought, sold and refined in the name of profit.

The decline of cash

When the pandemic began, cash had already been on the decline for years. In Australia, demand for coins fell by more than 50% between 2013 and 2019.

For many people, increasing digitisation is synonymous with progress. It can be seen as a way of leaving the cumbersome, historical artefacts of coins and banknotes behind.

COVID-19 has accelerated this move away from cash. Wariness of microbe-ridden banknotes has seen contactless payment become a spontaneous public health standard.

Because cash is a social material, it moves between us, connecting us both financially and physically. The US Federal Reserve even decided to quarantine dollars returning from Asia earlier this year in an attempt to stop the coronavirus crossing its borders.

Read more:

Depending on who you are, the benefits of a cashless society are greatly overrated

Dropping digital breadcrumbs

One perk of paper money is that it does not leave paper trails. Digital money, however, leaves traces in the databases of banks, vendors and platform owners, while governments look keenly over their shoulders.

Financial journalist Brett Scott calls this a “prison of watchable payments”.

Tax officials love digital transactions because they make it easier to monitor the nation’s economy. Banks and payment platforms are pleased as well: not only do they collect fees and gain the ability to allow or obstruct transactions, they can also profit from the troves of personal data piling up on their servers.

Internally, banks use this data to offer you other bespoke services such as loans and insurance. But information is also aggregated to better understand wider economic trends, and then sold on to third parties.

At the moment, these data metrics are anonymised but that doesn’t guard against retailers using de-anonymising techniques to attach transactions back to your identity.

Data brokers exist for this very reason: building digital profiles and creating a marketplace for them. This allows retailers to target you with tailored advertisements based on your spending. The devices at everyone’s fingertips become a feedback loop of information in which companies analyse what people have bought and then urge them to buy more.

Read more:

Explainer: what is surveillance capitalism and how does it shape our economy?

Can surveillance work on your behalf?

Having records of every transaction can also be useful for individuals. Companies such as Revolut and Monzo offer “spending analytics” services to help customers manage their money by tracking where it goes each month.

But information about a user’s own behaviour never truly belongs to them. And, as the digital economist Nick Srnicek explains, “suppression of privacy is at the heart of the business model”.

Digital payment with (some) privacy

While filling virtual baskets or paying by tapping a card does open up transactions for inspection, there are still ways you can protect your health and your data at the same time.

“Virtual cards” like those provided by privacy.com are one useful tool. These services let users create multiple card numbers for different online purchases that conceal consumption patterns from banks and credit card details from merchants.

Cryptocurrencies might also find a new limelight in the pandemic. Hailed as cash for the internet, the inbuilt privacy mechanisms of Bitcoin, Zcash and Monero could work to mask transactions.

However, finding companies that accept them is challenging, and their privacy capabilities are often overstated for everyday users. This is particularly true when using exchanges and third-party wallet software such as Coinbase.

In brick-and-mortar stores, staying under the radar can be more difficult. Prepaid cards are one option – but you’ll need to buy the card itself with cash if you want to keep your anonymity fully intact. And that takes us back to square one.![]()

Jack Parkin, Digital Economist, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It’d be a mistake to shut financial markets: more than ever, we need them to work

Stephen Kirchner, University of Sydney

The extreme volatility and losses seen in stock markets in recent weeks has seen calls for financial markets to be closed and short selling restricted.

But shutting them down would be a mistake.

Amid the volatility, financial market prices convey much needed information.

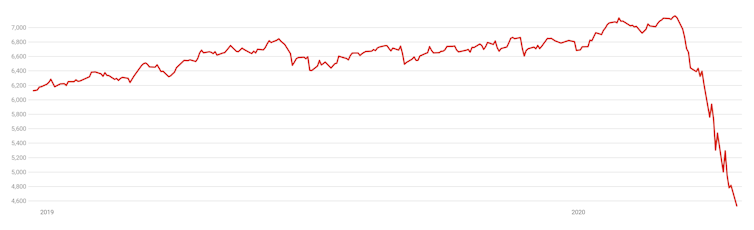

S&P/ASX 200 share index over the past year

Source: Yahoo Finance

In an early morning meeting at the White House the day after the 1987 stock market crash, then US Treasury Secretary Jim Baker floated the idea of closing the stock market.

The Chair of President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers, the Chicago-trained monetarist Beryl Sprinkel, was having none of it.

According to several second and third-hand accounts, when his opinion was sought, Sprinkel said “we will close the markets when monkeys come flying out of my ass.”

When Reagan asked Fed Chair Alan Greenspan for his opinion, Greenspan declared, “I go with the monkeys”.

The US stock market stayed open that day and rallied late in the afternoon, injecting a note of much-needed confidence.

Prices tell us truths

The Fed’s operations to maintain liquidity (the ability to buy and sell) remain a textbook case of how to respond to severe financial market stress.

The US economy was spared recession on that occasion.

Today’s situation is different in important respects. Policymakers are choosing to shut down the economy, and financial markets are pricing shares accordingly. Bond markets have been shaken as investors sell bonds to raise cash and prepare for governments to issue a flood of new bonds.

Read more:

More than a rate cut: behind the Reserve Bank’s three point plan

The US dollar has rallied as the world scrambles for US dollars, sending exchange rates against the US dollar dramatically lower.

As my previous research shows, the US dollar often climbs when the economic outlook is most dire, explaining why the Australian dollar is at its lowest in nearly two decades.

US cents per Australian dollar

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

Amid such extreme volatility, it would be tempting to close financial markets, in particular, stock exchanges.

There is no reason to close markets for reasons of public health. Financial markets are now traded almost entirely electronically. The US has been forced to close its trading floors in New York and Chicago, but these trading floors were already legacies of an earlier era, largely ornamental adornments to digital trading.

Stock markets have their own circuit breakers that kick in during extreme volatility, but to do more than that would be to deprive traders and policymakers of the insights they offer.

Price movements function as alerts. It is noteworthy that financial markets sold off days before the World Health Organisation finally declared a pandemic.

Read more:

This coronavirus share market crash is unlike those that have gone before it

They can also inform policymakers about what to do. When share markets begin a sustained recovery, it will be a sign the worst of the pandemic might be behind us.

We need prices for financial products in the same way we need prices for goods and services. Without them, decision-making becomes difficult, if not impossible.

Preventing investors from selling stocks to raise cash (which is what a stock market shutdown would do) could cause severe hardship.

With share market prices falling sharply, it’s tempting to think closing them will stem the losses, but it could trigger even more painful adjustments elsewhere.

Even short sellers have a place

Other countries have imposed bans on short selling, which is the sale of a share the seller does not yet own.

Short sellers profit by buying back shares at a lower price after they have sold them. They do it by borrowing rather than owning stocks. Their actions help the owners of stocks who want to protect their financial positions from further declines in price.

If owners can’t protect themselves in this way, they can be forced to liquidate shares, making the downturn even worse.

Read more:

Coronavirus market chaos: if central bankers fail to shore up confidence, then what?

The global financial crisis gave us a wealth of experience with bans on short-selling, including in Australia. The evidence from that experience overwhelmingly suggests short-selling bans were counter-productive.

Keeping markets open will be a painful experience for many, but closing them is the equivalent of shooting the messenger.

Eventually, they will signal better times ahead and give business the confidence to move forward with the recovery.![]()

Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Frydenberg outlines financial sector reform timetable

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has issued a timetable for the government’s dealing with the recommendations from the royal commission into banking, superannuation and financial services, which aims to have all measures needing legislation introduced by the end of next year.

The opposition has accused the government of dragging its feet on putting into effect the results of the inquiry, which delivered its final report early this year.

“The need for change is undeniable, and the community expects that the government response to the royal commission will be implemented swiftly,” Frydenberg said in a statement on the timetable.

Fydenberg said that in his final report Commissioner Kenneth Hayne made 76 recommendations – 54 directed to the federal government (more than 40 of them needing legislation), 12 to the regulators, and 10 to the industry. Beyond the 76 recommendations, the government had announced another 18 commitments to address issues in the report.

The government had implemented 15 of the commitments it outlined in responding to the report, Frydenberg said. This included eight out of the 54 recommendations, and seven of the 18 additional commitments the government made. “Significant progress” had been made on another five recommendations, with draft legislation in parliament or out for comment or consultation papers produced.

Read more:

Grattan on Friday: How ‘guaranteed’ is a rise in the superannuation guarantee?

Frydenberg said that, excluding the reviews to be conducted in 2022, his timetable was:

-

by the end of 2019, more than 20 commitments (about a third of the government’s commitments) would have been implemented or have legislation in parliament

-

by mid 2020, more than 50 commitments would have been implemented or be before parliament

-

by the end of 2020, the rest of the commission’s recommendations needing legislation would have been introduced.

When the Hayne report was released early this year, the government agreed to act on all the recommendations.

But one recommendation it has notably not signed up to was on mortgage brokers.

Hayne found that mortgage brokers should be paid by borrowers, not lenders, and recommended commissions paid by lenders be phased out over two to three years.

Read more:

Wealth inequality shows superannuation changes are overdue

The government at first accepted most of this recommendation, announcing the payment of ongoing so-called “trailing commissions” would be banned on new loans from July 2020. Upfront commissions would be the subject to a separate review. Four weeks later in March Frydenberg announced the government wouldn’t be banning trailing commissions after all. Instead, it would review their operation in three years.

Releasing the timetable, Frydenberg said the reform program was the “biggest shake up of the financial sector in three decades” and the speed of implementation “is unprecedented”.

“It will be done in a way that enhances consumer outcomes with more accountability, transparency and protections without compromising the flow of credit and competition,” he said.

He undertook to ensure the opposition was briefed on each piece of legislation before it came into parliament.

“This will begin with the offer of a briefing by Treasury on the implementation plan. Given both the government and opposition agreed to act on the commission’s recommendations, we expect to achieve passage of relevant legislation without undue delays,” he said.

He said the industry was “on notice. The public’s tolerance has been exhausted. They expect and we will ensure that the reforms are delivered and the behaviour of those in the sector reflects community expectations.”![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Compensation scheme to follow Hayne’s indictment of financial sector

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

The Morrison government has promised to establish a compensation scheme of last resort – paid for by the financial services industry – as it seeks to avoid the outcome of the banking royal commission becoming a damaging election issue for it.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, releasing Commissioner Kenneth Hayne’s three-volume report which excoriates the financial sector, said the government would be “taking action” on all 76 recommendations.

The commissioner has made 24 referrals to the regulatory authorities over entities’ conduct in specific instances. All the major banks have been referred except Westpac. AMP, Suncorp, Allianz and Youi are among entities that have been referred.

Commissioner Hayne has made civil and criminal conduct referrals – he was dealing with entities rather than individuals.

In an indictment of years of bad behaviour which has left many customers devastated, Hayne says “there can be no doubt that the primary responsibility for misconduct in the financial services industry lies with the entities concerned and those who managed and controlled those entities”.

“Rewarding misconduct is wrong. Yet incentive, bonus and commission schemes throughout the financial services industry have measured sales and profit, but not compliance with the law and proper standards,” the commissioner says.

“Entities and individuals acted in the ways they did because they could.

“Entities set the terms on which they would deal, consumers often had little detailed knowledge or understanding of the transaction and consumers had next to no power to negotiate the terms.”

Hayne says that “too often, financial services entities that broke the law were not properly held to account.

“The Australian community expects, and is entitled to expect, that if an entity breaks the law and causes damage to customers, it will compensate those affected customers. But the community also expects that financial services entities that break the law will be held to account.”

The commissioner stresses that “where possible, conflicts of interest and conflicts between duty and interest should be removed” in financial services.

Hayne says that because it was the financial entities, their boards and senior executives, who bore primary responsibility for what had happened, attention must be given to their culture, governance and remuneration practices.

Changes to the law were “necessary protections for consumers against misconduct, to provide adequate redress and to redress asymmetries of power and information between entities and consumers”.

The commission’s multiple recommendations propose:

-

simplifying the law so that its intent is met

-

removing where possible conflicts of interest

-

improving the effectiveness of the regulators, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC)

-

driving cultural change in institutions and increasing their accountability

-

increasing protection for consumers from “misconduct or conduct that falls below community standards and expectations”, and providing for remediation.

The government has provided point-by-point responses to the recommendations.

The commission had seven rounds of public hearings with about 130 witnesses, and reviewed more than 10,000 public submissions. It dealt with banking, financial advice, superannuation and insurance.

While there have been claims the fallout from the commission could risk a further tightening of credit for small business in particular, Hayne has been careful in his report to minimise that danger.

But he makes it clear there should be no excuse for avoiding needed action. “Some entities used the undoubted need for care in recommending change as a basis for saying that there should be no change. The ‘Caution’ sign was read as if it said ‘Do Not Enter’.”

The commissioner has some sharp words for the NAB in his report, saying that “having heard from both the CEO Mr Thorburn, and the Chair, Dr Henry, I am not as confident as I would wish to be that the lessons of the past have been learned.

“More particularly, I was not persuaded that NAB is willing to accept the necessary responsibility for deciding, for itself, what is the right thing to do, and then having its staff act accordingly. I thought it telling that Dr Henry seemed unwilling to accept any criticism of how the board had dealt with some issues.

“I thought it telling that Mr Thorburn treated all issues of fees for no service as nothing more than carelessness combined with system deficiencies […] Overall, my fear – that there may be a wide gap between the public face NAB seeks to show and what it does in practice – remains.”

Among his specific recommendations Hayne says that grandfathering provisions for conflicted remuneration “should be repealed as soon as is reasonably practicable”. The government has said it will do this from January 2021.

Hayne proposes a new oversight authority that would monitor APRA and ASIC.

He lashes ASIC for not cracking down on fees for no service.

“Until this commission was established, ASIC and the relevant entities approached the fees for no service conduct as if it called, at most, for the entity to repay what it had taken, together with some compensation for the client not having had the use of the money.

“That is, the conduct was treated as if it was no more than a series of inadvertent slips brought about by some want of care in record keeping.”

In a number of recommendations about mortgage brokers, Commissioner Hayne says the borrower, not the lender, should pay the mortgage broker fee for acting on home lending. But the government is not accepting the proposal at this time.

In relation to the sale of products the commission recommends the removal of the exclusion of funeral expenses policies from the definition of “financial product”. It should be put “beyond doubt that the consumer protection provisions of the ASIC act apply to funeral expenses policies.”

On superannuation the commission says that “hawking” of superannuation products should be prohibited, and that a person should have only one default account.

In a statement Scott Morrison and Frydenberg said that in outlining its response to the commission “the government’s principal focus is on restoring trust in our financial system and delivering better consumer outcomes, while maintaining the flow of credit and continuing to promote competition.”

They said the government would expand the remit of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA) so it could award compensation for successful claims going back a decade.

Shadow treasurer Chris Bowen said that Labor accepted all the recommendations “in principle”.

“The government simply cannot say that they’ve accepted the recommendations … they’ve got weasel words in there about various recommendations,” he said.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Zimbabwe’s financial system is living on borrowed time – and borrowed money

Reuters/Philimon Bulawayo

Roger Southall, University of the Witwatersrand

Zimbabwe’s financial system increasingly resembles a house of cards. Were one card to give way – for instance, if South Africa’s power utility, Eskom, were to have the temerity to suggest that Zimbabwe actually pay for the electricity that it’s supplying the country – the entire edifice would collapse.

To put it another way, the government is bust. It is again printing money to cover its spiralling costs, and inflation is rising. And given that there’s an election looming in 2018, Zimbabwe’s ruling party, ZANU-PF doesn’t want to cut-back. Far from it, it wants to carry on spending, as fast as it can.

The rot goes back to the early 2000’s. ZANU-PF profligacy had been fuelled by acontinuous cycle of simply printing more money, and resultant runaway inflation. Mega-inflation meant that ordinary people lost their pensions and whatever savings they had, as the Zimbabwe dollar lost its value and people resorted to barter or the use of other currencies.

Ultimately, the government faced no choice but to accept reality. In 2008 it scrapped the Zimbabwe dollar in favour of a basket of other currencies, although within a short time, this meant in effect the reign of the US dollar.

“Dollarisation” allowed for the pursuit of more rational policies by the coalition Government of National Unity which followed the disputed 2008 election. However, its control of the electoral machinery ensured that ZANU-PF won a resounding victory in the 2013 election. Within a short space of time it returned to its familiar policy mix of profligacy, corruption and populist economics.

Yet ZANU-PF faced major problems. Above all, “dollarisation” meant that the cost of Zimbabwe’s exports on international markets was high. Worse, the dramatic collapse in agricultural production since the early 2000s (following the appropriation of white farms) alongside the decimation of the country’s manufacturing industries meant that there was relatively little to export anyway. Tobacco production has recovered a little, but the quality is less than it used to be, so returns are relatively less.

Meanwhile government insistence that mines should be 51% Zimbabwean owned has done nothing to entice inward investment or boost exports.

In short, the capacity of the economy to earn US dollars by selling goods externally has fallen dramatically, and the supply of money circulating within the country has dried up. Unemployment stands at around 90%.

President Robert Mugabe’s latest response has been to replace finance minister Patrick Chinamasa, who had been warning of the structure’s fragility in ever more urgent tones. The new finance minister is Ignatius Chombo, a party loyalist, who will brook no talk of any need for structural reform.

The bond notes

Faced by a looming crisis, the ZANU-PF government has resorted to three key strategies.

One has been the issue of “bond notes” (of different denominations) by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. Officially, they’re designed to swell the amount of money in circulation within the country. The problem is that apart from having no value outside the country, nobody trusts them as they have been issued by a ZANU-PF government, and it was this government that presided over the hyperinflation.

ZANU-PF’s announcement that it was issuing bond notes was met with a run on the banks as depositors sought to withdraw dollars as fast as they could. Their assumption was that this was a government ploy to reintroduce the Zimbabwean dollar. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe responded by limiting the amount of dollars individuals could withdraw.

People are reluctant to use the bond notes. But they’re still sometimes forced to accept them because of the sheer shortage of “real” money. As a result when they can, they rush off to the local bus station where they can sell them for dollars to currency traders – albeit illegally.

The second strategy has been the rapid expansion of country’s ability to manage electronic transactions. Its aim has been to expand the amount of money in circulation without using up “real” dollars.

Accordingly, government employees are now largely paid electronically Similarly, government employees (and everyone else) now pay nearly all their bills within the country electronically.

And Zimbabweans are rarely able to convert the notional sums of dollars they hold in the bank into real cash – unless they make use of the currency traders in illegal transactions.

Meanwhile, with the rate of inflation continuing to rise combined with the widespread lack of faith in the banks, many Zimbabweans spend their bank balances on consumer goods as quickly as possible rather than attempting to “save”. After all, if times get hard, you won’t be able to get rid of your bond notes, but you may be able to sell your fridge.

Fanciful financial system

But it’s the third strategy which the government has pursued which is really fuelling a fanciful financial system.

Since 2013, government expenditure has steadily increased year by year, despite the country earning very little internationally. The ZANU-PF government may have hoped to fund this by its old trick of literally printing money, that is, by expanding the supply of bond notes.

But such was the negative popular sentiment that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe seems to have restricted their issue. Supposedly the issue of bond notes is backed by a USD$200 loan by the Afreximbank, but no-one really knows how many have been issued because the central bank provides no information.

What the government has done instead is to fund its rising costs by issuing treasury bills (whereby the government touts for loans on the capital market against promises of later redemption). No-one in their right mind would want to buy them, but Zimbabwe’s banks today have little option. As inward investment into the country has dried up to a trickle, there is little else for them to spend their money on, and the interest rates that the government promises to pay are, at face value, attractively high.

The coalition government of national unity recorded budget surpluses for three of the four full years in which the opposition controlled the Treasury. For its part, the ZANU-PF government recorded deficits of USD$186 million and USD$125 million in 2014 and 2015. Recently, the then finance minister Chinamasa projected a deficit of USD$1.41 billion for 2017. As of June 30, 2017, there were USD$2.5 billion worth of Treasury bills on issue.

![]() In other words, the spending will continue. Zimbabwe’s financial system is living on borrowed time and borrowed money. It will again end in financial ruin, as it did in 2008. But all ZANU-PF cares about is ensuring that it wins the next election and allowing its political elite to “eat”.

In other words, the spending will continue. Zimbabwe’s financial system is living on borrowed time and borrowed money. It will again end in financial ruin, as it did in 2008. But all ZANU-PF cares about is ensuring that it wins the next election and allowing its political elite to “eat”.

Roger Southall, Professor of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Vital Signs: how likely is another financial crisis? It comes down to what we believe

Vital Signs is a weekly economic wrap from UNSW economics professor and Harvard PhD Richard Holden (@profholden). Vital Signs aims to contextualise weekly economic events and cut through the noise of the data affecting global economies.

This week: let’s take a break from the data and analyse why the Chair of the United States Federal Reserve says another financial crisis is unlikely in our lifetimes.

Last week I wrote in this column that Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe was not taken to giving boring speeches. This week, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen went him one better with her remarks to the British Academy.

Yellen said of the prospect of another financial crisis like that of 2008:

I do think we’re much safer, and I hope that it will not be in our lifetimes, and I don’t think it will be.

Her rationale was that the regulatory changes put in place since the crisis have made the system a great deal safer.

Yellen expressed her hope that these regulations would not be overturned, saying of attempts to do so:

We’re now about a decade after the crisis and memories do tend to fade, so I hope that won’t be the case, and I hope those of us who went through it will remind the public that it’s very important to have a safer, sounder financial system and that this is central to sustainable growth.

One piece of evidence supporting Yellen’s view were the so-called “stress tests” that the Federal Reserve has performed on US banks since 2011.

Just hours before this writing, the Fed approved plans for proposed dividend payouts for all 34 firms taking part in their annual stress tests. This is the first time since the annual stress tests began that all participating firms got a passing grade from the Fed.

So what should we make of Yellen’s prediction? This doesn’t have the ring of “confidence-boosting” rhetoric. It seems as though this is her genuine view.

At this point I should make two things clear. One: I have enormous respect for Janet Yellen, and two: I was fairly surprised by her remarks. So how does one reconcile these?

We still don’t know what caused the global financial crisis

It’s important to understand that the proximate cause of the financial crisis was a kind of “bank run on the system”. In a classic bank run – like the ones of the Great Depression – depositors go from believing that other depositors think their banks are safe, and are therefore willing to leave their money there, to believing that others consider the banks unsound.

Once investors believe that other investors are going to run on the bank, they want to run too (because banks typically hold less than 10% of the cash required to pay back all depositors). In the language of game theory, there is a switch from the “good equilibrium” to the “bad equilibrium”.

In the financial crisis there wasn’t a run on traditional banks so much as on investment banks and other financial institutions. This led to credit markets drying up (such as the commercial debt and “repo” markets).

What caused this shift in beliefs is a hotly debated issue. The large increase in US house prices and imprudent lending by US mortgage originators played an important role. The use of collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) and synthetic versions of CDOs were important. Lack of regulator controls allowed these things to happen, and incentives within financial institutions facilitated and encouraged risk and bad behaviour.

Yet for quite a long time the “good equilibrium” prevailed. What caused the switch?

That is the big question, and I’m pretty confident that not even Yellen knows the answer.

It all comes down to what we believe

What Yellen does seem to be saying is that regulatory responses to the crisis have made it much less likely that bad behaviour is going to occur. That certainly seems plausible. And if there is no – or very little – bad behavior, then beliefs about what other believe may not be particularly important.

But if there is a view that some new form of moral hazard is taking place, and people lose faith in the regulatory regime, then perhaps 2008 could occur again. And soon.

As game theory – and the lessons of the classic depression-era bank runs – teach us, it all comes down to what people believe about what other people believe.

![]() That seems like a pretty slippery object to me.

That seems like a pretty slippery object to me.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Australian Politics: 14 July 2013

With the return of Kevin Rudd as Prime Minister in Australia, things have been moving along fairly quickly in Australian politics. Time of course is running out as an election looms, so time is necessarily of the essence. One of the areas that the ALP has moved to address is the carbon tax, with Kevin Rudd’s government moving toward an emissions trading scheme. This has brought the typical and expected responses from the opposition, as well as charges of hypocrisy from the Greens. For more visit the following links:

The link below is to an article that pretty much sums up the situation currently in Australian politics I think – well worth a read.

For more visit:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jul/12/tony-abbott-fall-stunt-men

Also causing continuing angst in Australia is the issue of asylum seekers and boat people. There has been even more terrible news from the seas surrounding Christmas Island, with yet another asylum seeker tragedy involving a boat from Indonesia.

Around the edges of the mainstream parties are those of Bob Katter and Clive Palmer. There are stories of an alleged financial offer from Clive Palmer’s ‘Palmer United Party’ to join with ‘Katter’s Australian Party’ for $20 million dollars and form the combined ‘Katter United Australian Party.’ For more visit the links below:

– http://www.news.com.au/breaking-news/national/palmer-denies-deal-with-katters-party/story-e6frfku9-1226679175607

– http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-07-14/katter2c-palmer-at-odds-over-claims-mining-magnate-offered-fin/4819098

And finally, for just a bit of a chuckle – not much of one – just a small chuckle, have a read of the following article linked to at:

Cyprus: Financial Jitters

The link below is to an article reporting on the latest financial jitters to hit the world economy and the continuing crisis in Cyprus.

For more visit:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2013/apr/12/gold-selloff-cyprus-eurozone-crisis

Portugal: Financial Crisis

You must be logged in to post a comment.