Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Peter Martin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National UniversityAustralia’s top economists have overwhelmingly rejected cuts to either permanent or temporary migration as a means of restoring lost wage growth.

The 56 leading economists polled by the Economic Society and The Conversation include a former head of the Fair Pay Commission and a former expert member of the Fair Work Commission’s minimum wage panel.

Among the experts, selected by their peers, are specialists in economic modelling and the economics of labour markets from both the private and public sectors.

All but five rejected cuts in temporary migration as a means of boosting wage growth. All but three rejected cuts in permanent migration.

The results put the economists at odds with Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe, who last month drew a link between temporary migration and weak wage growth saying employers had been using overseas hires to fill gaps that would have been filled by locals, diluting “upward pressure on wages in these hotspots”. He said this might have spilled over to rest of the labour market.

Cutting temporary and cutting permanent migration were the first two of ten options for boosting wage growth presented to the panel of economists. The panel rated them third last and second last. Only “holding back growth in female and older worker participation” was marked down more.

Each economist was asked to pick three of the ten options. The most popular, picked by 78.2%, was measures to boost productivity growth. The next most popular, picked by 50.9%, was measures to boost business investment.

Michael Keane of The University of NSW said the idea that population growth and increased labour supply were constraining wage growth was “so naive as to not really be worthy of comment”.

Consultant Rana Roy said only a “cultivated amnesia” could ignore the near-uninterrupted growth in real wages in US, industrialised Europe and Australia amid record inbound immigration in the decades after the second world war.

Gabriela D’Souza of the Committee for Economic Development of Australia said the idea owed much to a “one dimensional view of the world” that took account of only the direct impact of immigrants on particular wages and not the impact of their demand for goods and services on a broader range of wages.

Dozens of studies had identified the overall impact as “near zero”.

Productivity ‘almost everything’

Robert Breunig of the Australian National University said immigrants appeared to add to productivity rather than detract from it, meaning slowing down immigration could slow down rather than add to productivity and growth.

Three quarters of the panel nominated productivity growth as the most important precondition for higher wages growth, endorsing the conclusion of Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman that “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.”

Krugman famously added that a country’s ability to improve its standard of living

over time depended “almost entirely on its ability to raise its output

per worker”.

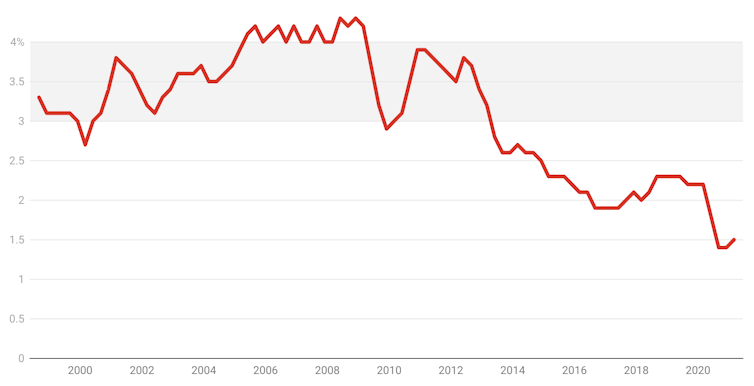

Wages growth is way below the Reserve Bank’s +3% target

ABS Wage Price Index

Ian Harper, a former head of the Howard government’s Fair Pay Commission and a current member of the Reserve Bank board, said that without productivity growth, any boost in wages growth that was delivered was likely to be nominal — matched by inflation — rather than real, delivering higher living standards.

One of the best tools for lifting production per worker was business investment.

One of the five economists who thought immigration hurt wages growth, Macquarie University’s Geoffrey Kingston, said it seemed to do it by thinning investment per worker. In the 1980s, under Prime Minister Bob Hawke, increased immigration helped push down real wages for five years in a row.

Several of those surveyed said wage growth needed investment in more than machines. Griffith University’s Fabrizio Carmignani said what also mattered was investment in “human capital” via education and research and development.

Read more:

Exclusive. Top economists back unemployment rate beginning with ‘4’

Adrian Blundell-Wignall, a former division chief at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, said reforming the education system and getting rid of elitism had to be part of the plan.

“That the best predictor of how well you do at school is how rich your parents are and where they went to school is a national tragedy,” he said. “The entitlement and club economy that comes with this permeates politics, business, and who gets the best jobs after completing school.”

Former Rudd and Gillard government minister Craig Emerson said while measures to boost productivity growth were essential, even if implemented soon, they would take years to flow through into higher wages.

It’s how you divide the pie

Saul Eslake said whether or not higher productivity growth actually delivered higher real wages would depend on the division of the fruits of that growth between wages and profits.

John Quiggin said nearly every reform of Australia’s industrial relations system since 1975 had acted to reduce the bargaining power of unions. All ought to be reviewed with a “presumption in favour of repeal”.

Mala Raghavan of the University of Tasmania said wage growth had become uneven. Wages for a small number of managers had soared while wages for others — especially casual workers — had barely moved.

Read more:

Top economists want JobSeeker boosted $100+ per week, tied to wages

The Australian National University’s Emily Lancsar saw a triple benefit from reforming the industrial relations system to boost union bargaining power: it would increase wages directly, it would put money that would have been paid out as profits in the hands of people likely to spend it, and the increases would flow through to workers not on awards and not represented by unions.

Labour market specialist Jeff Borland added that there was a case for strengthening the ability of unions to obtain gender pay equity in female-dominated occupations.

None of those surveyed were optimistic about the prospect of quickly lifting wages growth. The Reserve Bank said in July it wasn’t planning to lift interest rates until aggregate growth exceeded 3%.

Detailed responses:

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.