Robert Breunig, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Opponents of Australia’s strong immigration program will be disappointed.

In announcing a cut in Australia’s migration ceiling from 190,000 to 160,000 per year, federal population minister Alan Tudge launched an all-out defence of immigration as a driver of economic prosperity.

It has not only boosted gross domestic product and budget revenue, as would be expected when with more people, but also also living standards – measured as GDP per person. Tudge explained:

This is often not sort of fully understood. Not only does population growth help with GDP growth overall, but it helps with GDP per capita growth too. It’s actually made all of us wealthier.

In fact, Treasury estimates that 20% of our per capita wealth generated over the last 40 years has been due to population factors. How does that come about? In part because when we bring in migrants, they come in younger than what the average Australian is. On average, a migrant comes in at the age of 26. The average age of an Australian is about 37. So it very much helps with our workforce participation, and that’s essentially a big driver of our GDP per capita growth.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison added:

I would also mention from a pensions point of view and social welfare point of view, achieving more of a balance in the working-age population means there’s more people in the working age to actually pay for the pensions and the welfare bill for those who aren’t able to be in the workforce and with an ageing population.

The lower ceiling announced on Wednesday will make little difference to Australia’s migrant intake. It is already close to 160,000, at about 162,000. Other changes will attempt to influence where migrants settle.

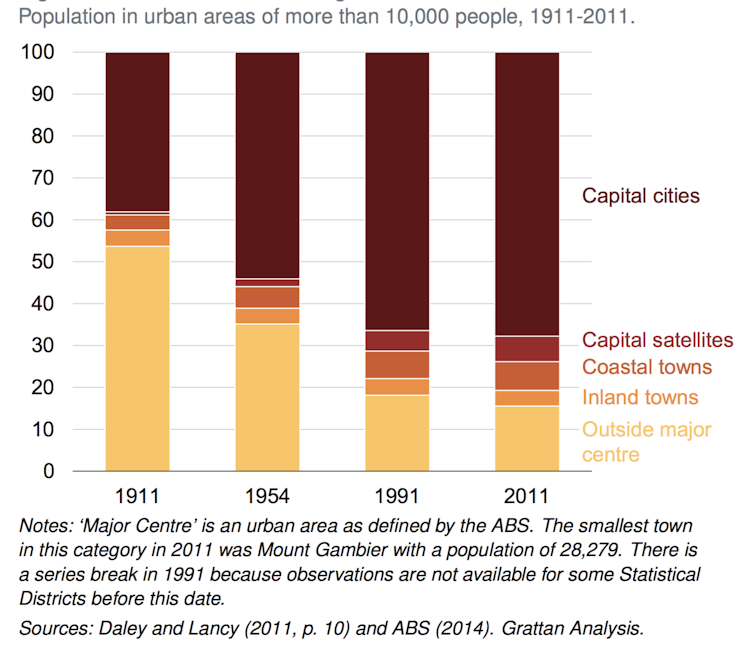

Two new regional visas for skilled workers will require them to live and work in less urban Australia (outside of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and the Gold Coast) for three years before being able to become a permanent resident. Of the 160,000 potential places, 23,000 will be set aside for these visa-holders. International students studying outside the big cities will get access to an extra year in Australia on a post-study work visa.

Immigration shouldn’t supress wages

Tudge’s acceptance that migration neither boosts unemployment nor cuts wages is consistent with most evidence from Australia and overseas.

New arrivals increase the supply of workers (such as teachers and house-builders), which might be expected to depress existing residents’ wages. But there are two countervailing forces.

First, migrants also increase the demand for goods and services (as the arrivals’ children get taught and their homes get built), which might be expected to boost preexisting residents’ wages.

Second, if migrants fill jobs that would otherwise go unfilled, they can boost the productivity, and hence the wages, of existing residents.

Most studies of migration shocks, such as the repatriation of more than a million French citizens to metropolitan France after the Algerian civil war, have found that the net effect is close to zero.

There is hardly any evidence that it does

An exception is work in the United States by George Borjas, who found that the boatlift of 125,000 mostly low-skilled immigrants from Cuba to Miami in 1980 did suppress the wages of low-skilled Miami workers, if not Miami workers overall. But this finding has been disputed.

In 2015 Nathan Deutscher, Hang Thi and I set out to replicate his work, using changes in the immigration rates of different skill groups to Australia to identify the effects of immigration on the earnings and employment prospects of particular groups of Australian workers.

Our data came from the Australian Census, the Surveys of Income and Housing, and the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey.

We isolated 40 distinct skill groups at a national level, identifying them with a combination of educational attainment and workforce experience and examined six outcomes – annual earnings, weekly earnings, wage rates, hours worked, labour market participation rate, and unemployment.

We explored 114 different possibilities, controlling for macroeconomic conditions and for the fact that immigrants to Australia are disproportionately highly skilled with higher wages.

In Australia, we found next to none

We found immigration had no overall impact on the wages of incumbent workers. If anything, the effect was slightly positive.

Some of our estimates showed immigration had a negative effect on some groups of incumbent workers, but the positive effects outnumbered negative effects by three to one. The vast majority of effects were zero.

The statistical basis for our finding of no overall effect was incredibly strong. It more than passed the standard tests.

Our research only looked at one, very limited, aspect of immigration. Immigrants can also bring cultural and demographic benefits. And until infrastructure catches up, they can increase congestion.

But immigration doesn’t seem to harm either jobs or wages, a point the Morrison government is right to acknowledge.

Read more:

Solving the ‘population problem’ through policy

![]()

Robert Breunig, Professor of Economics and Director, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.