Shutterstock

Ritesh Chugh, CQUniversity AustraliaIf you’ve ever gotten your phone wet in the rain, dropped it in water or spilt liquid over it, you’re not alone. One study suggests 25% of smartphone users have damaged their smartphone with water or some other kind of liquid.

Liquid penetrating a smartphone can affect the device in several ways. It could lead to:

- blurry photos, if moisture gets trapped in the camera lens

- muffled audio, or no audio

- liquid droplets under the screen

- an inability to charge

- the rusting of internal parts, or

- a total end to all functionality.

While new phones are advertised as “water resistant”, this doesn’t mean they are waterproof, or totally immune to water. Water resistance just implies the device can handle some exposure to water before substantial damage occurs.

Samsung Australia has long-defended itself against claims it misrepresents the water resistance of its smartphones.

In 2019, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) took Samsung to Federal Court, alleging false and misleading advertisements had led customers to believe their Galaxy phones would be suitable for:

use in, or exposure to, all types of water (including, for example, oceans and swimming pools).

Samsung Australia subsequently denied warranty claims from customers for damage caused to phones by use in, or exposure to, liquid.

Similarly, last year Apple was fined €10 million (about A$15.5 million) by Italy’s antitrust authority for misleading claims about the water resistance of its phones, and for not covering liquid damage under warranty, despite these claims.

How resistant is your phone?

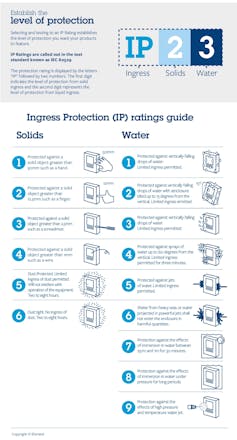

The water resistance of phones is rated by an “Ingress Protection” code, commonly called an IP rating. Simply, an electrical device’s IP rating refers to its effectiveness against intrusions from solids and liquids.

The rating includes two numbers. The first demonstrates protection against solids such as dust, while the second indicates resistance to liquids, specifically water.

Element Materials Technology

A phone that has a rating of IP68 has a solid object protection of 6 (full protection from dust, dirt and sand) and a liquid protection of 8 (protected from immersion in water to a depth of more than one metre).

Although, for the latter, manufacturers are responsible for defining the exact depth and time.

The popular iPhone 12 and Samsung Galaxy S21 phones both have a rating of IP68. However, regarding exposure to water, the iPhone 12 has a permissible immersion depth of a maximum of 6m for 30 minutes, whereas the Galaxy 21’s immersion limit is up to 1.5m, also for 30 minutes.

While IP ratings indicate the water-repellent nature of phones, taking most phones for a swim will land you in deep trouble. The salt content in oceans and swimming pools can corrode your device and cost you a hefty replacement.

Moreover, phone manufacturers carry out their IP testing in fresh water and Apple recommends devices not be submerged in liquids of any kind.

Luckily, water resistant phones are generally able to survive smaller liquid volumes, such as from a glass tipping over.

Read more:

Screwed over: how Apple and others are making it impossible to get a cheap and easy phone repair

Checking for liquid damage

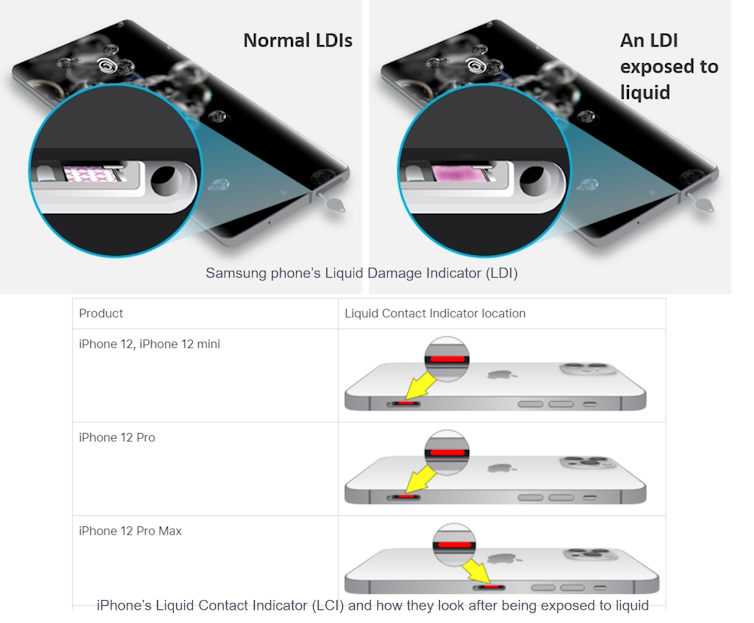

Exposure to water is something manufacturers have in mind when designing phones. Most Apple and Samsung phones come with a liquid contact/damage indicator strip located inside the SIM card tray.

This is used to check for liquid damage that may be causing a device to malfunction. An indicator strip that comes in contact with liquid loses its usual colour and becomes discoloured and smudgy.

Samsung/Apple

A discoloured strip usually renders your phone ineligible for a standard manufacturer warranty.

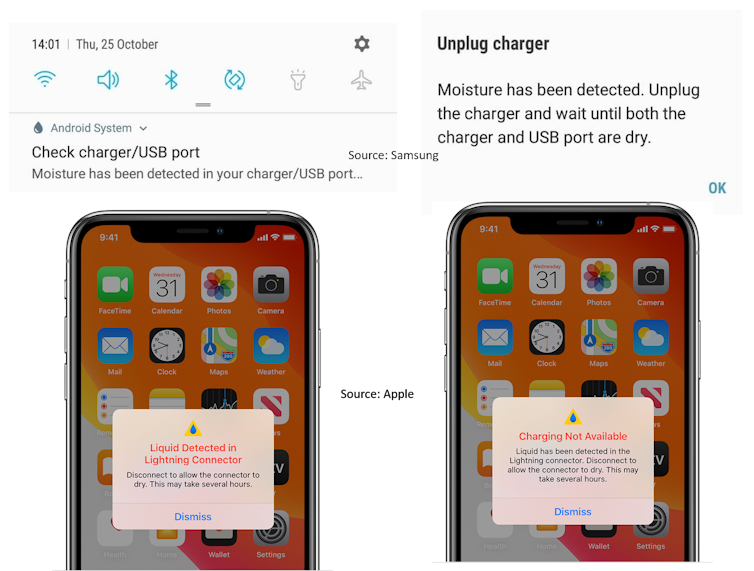

If you have any of the more recent smartphones from Apple or Samsung, then your device will be able to detect liquid or moisture in its charging port and will warn you with an alert. This notification only goes away once the port is dry.

Samsung/Apple

But what should you do if this dreadful pop-up presents itself?

Fixing a water-logged phone

Firstly, do not put your phone in a container of rice. It’s a myth that rice helps in drying out your phone. Instead, follow these steps:

- Turn off the device immediately and don’t press any buttons.

- If your phone is water resistant and you’ve spilt or submerged it in a liquid other than water, both Apple and Samsung recommend rinsing it off by submerging it in still tap water (but not under a running tap, which could cause damage).

- Wipe the phone dry with paper towels or a soft cloth.

- Gently shake the device to remove water from the charging ports,

but avoid vigorous shaking as this could further spread the liquid inside. - Remove the SIM card.

- Use a compressed aerosol air duster to blow the water out if you have one. Avoid using a hot blow dryer as the heat can wreck the rubber seals and damage the screen.

- Dry out the phone (and especially the ports) in front of a fan.

- Leave your phone in an airtight container full of silica gel packets (those small packets you get inside new shoes and bags), or another drying agent. These help absorb the moisture.

- Do not charge the phone until you are certain it’s dry. Charging a device with liquid still inside it, or in the ports, can cause further damage. Apple suggests waiting at least five hours once a phone appears dry before charging it (or until the alert disappears).

If the above steps don’t help and you’re still stuck with a seemingly dead device, don’t try opening the phone yourself. You’re better off taking it to a professional.

Read more:

Upgrade rage: why you may have to buy a new device whether you want to or not

![]()

Ritesh Chugh, Senior Lecturer – Information Systems and Analysis, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.