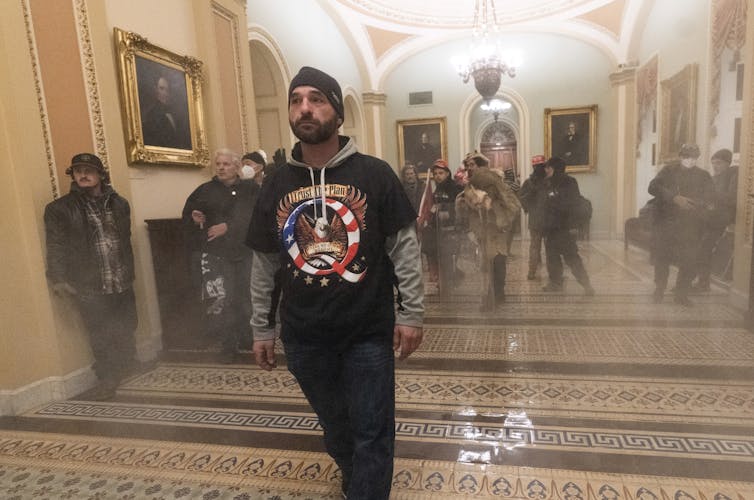

AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin

James D. Long, University of Washington and Victor Menaldo, University of Washington

When a mob attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 and stopped Congress from certifying Joe Biden as the nation’s next president, it was scary – and fatal for at least five people.

But it did not pose a serious threat to the nation’s democracy.

An attempt at an illegal power grab somehow keeping Donald Trump in the Oval Office was never likely to happen, let alone succeed. Trump always lacked the authority, and the mass support, required to steal an election he overwhelmingly lost. He didn’t control state election officials or have enough influence over the rest of the process to achieve that goal.

Nevertheless, over his term as president, he repeatedly violated democratic norms, like brazenly promoting his own business interests, interfering in the Justice Department, rejecting congressional oversight, insulting judges, harassing the media and failing to concede his election loss.

However, as scholars who study democracy historically and comparatively, we predict that the biggest threats to democracy Trump poses won’t emerge until after he exits the White House – when Biden will have to face the Trump presidency’s most serious challenges.

Brendan Smialowski, Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

It wasn’t a coup

Trump never really threatened a coup, which is a swift and irregular transfer of power from one executive to another, where force or the threat of force installs a new leader with the support of the military. Coups are the typical manner in which one dictator succeeds another.

A coup displacing a legitimately elected government is quite rare; prominent examples from the past 100 years across the world include Spain in 1923, Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Brazil in 1964, Greece in 1967, Chile in 1973, Pakistan in 1999 and Thailand in 2006.

A military-backed takeover was not going to happen in the U.S. Its armed forces are extremely unlikely to intervene in domestic politics for regime change, especially not in favor of a president who is historically unpopular among its ranks.

Even if Trump’s most ardent supporters believe he won, there aren’t enough of them to credibly threaten a civil war. Despite their ability to breach a thinly defended Capitol, a sustained insurrection would be easily quashed by law enforcement.

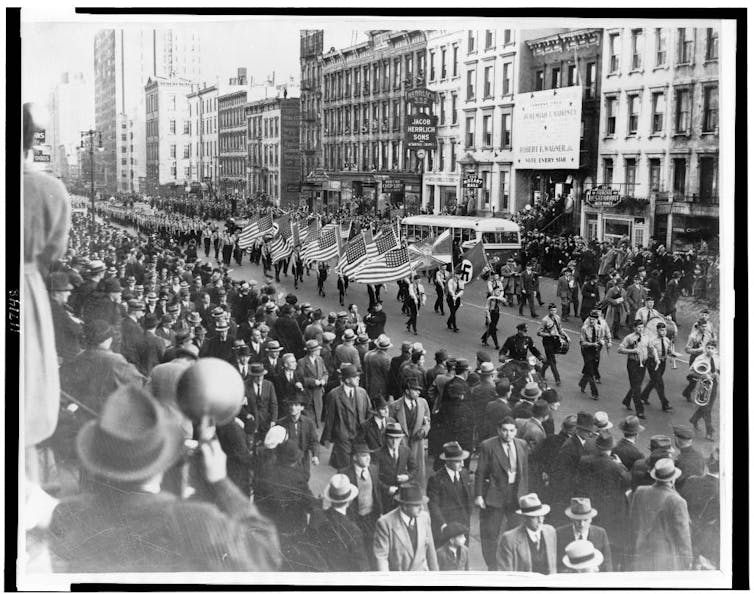

Trump couldn’t even stage an “auto-coup,” which happens when an elected executive declares a state of emergency and suspends the legislature and judiciary, or restricts civil liberties, to seize more power. There have also been very few of those perpetrated against democratically elected governments over the last 100 years. The most prominent examples are Hitler’s Germany in 1933, Bordaberry in Uruguay (1972), Fujimori in Peru (1992), Erdoğan in Turkey (2015), Maduro in Venezuela (2017), Morales in Bolivia (2019) and Orbán in Hungary (2020).

A U.S. president can’t dismiss the legislative or judicial branches, and elections are not under his control: The Constitution declares that they are run by the states. And the declaration of election results is also well outside the power of the president (or vice president). It doesn’t matter whether the losing side formally concedes; the new president’s term begins at noon on Jan. 20.

The attack on the Capitol may have threatened the lives of federal legislators and Capitol police officers, but the most it achieved was to interrupt, briefly, a ministerial procedure. Within hours, both the House and Senate were back in session in the Capitol, carrying on their certification of the electoral votes cast in 2020.

AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana

Still a threat to democracy

By objecting to the outcome of the election, Trump highlighted aspects of the process that many Americans were previously unaware of, ironically ensuring the public is better informed about the mechanics and details of American elections. In that way, he may have, paradoxically, made American democracy stronger.

And it was fairly strong already. There was no evidence of any sort of widespread fraud or other irregularities. Major media organizations continue to explain and document the facts regarding the election, contradicting the president’s disinformation campaign. In 2020, voter turnout was higher than it has been for a century. Despite the pandemic, Trump’s rhetoric and threats of foreign tampering, the 2020 elections were the most secure in living memory.

But beyond elections, Trump has threatened America’s other bedrock political institutions. While there are many seemingly disparate examples of his disregard for the Constitution, what unites them is impunity and contempt for the rule of law. He has committed numerous impeachable acts – including potentially the incitement-to-riot on Jan. 6. He is facing a criminal investigation in New York state, and may be looking at federal inquiries both about possible misdeeds he committed in office and from before he became president.

The framers of the Constitution feared many things they designed the U.S. government to defend against, but perhaps one anxiety eclipsed all others: a lawless president who never faces justice, and was never held accountable during or even after leaving office. As Alexander Hamilton wrote, “if the federal government should overpass the just bounds of its authority and make a tyrannical use of its powers, the people, whose creature it is, must appeal to the standard they have formed, and take such measures to redress the injury done to the Constitution.”

There’s very little time left to hold Trump to account during his term. After the events of Jan. 6, he now faces public backlash from longtime congressional allies and resignations from his Cabinet. He has also been locked out of Facebook and Twitter.

But the question of real, lasting – and legal – accountability will fall to Biden, and his nominee for attorney general, Merrick Garland. They will decide whether to continue existing investigations and potentially start new ones. State attorneys general and local prosecutors will have similar powers for the laws they enforce.

The aftermath

Newly elected leaders can often face strong incentives – and encouragement – to prosecute their predecessors, as Biden does now. But that approach, often called restorative justice, can also destabilize democracy’s prospects if lame-duck executives anticipate this and decide to hunker down and fight instead of conceding defeat. Consider Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi, toppled by Western military intervention and killed by his people in 2011. He refused to flee or seek asylum for fear that both foreign governments and his own successors would prosecute him for human rights violations.

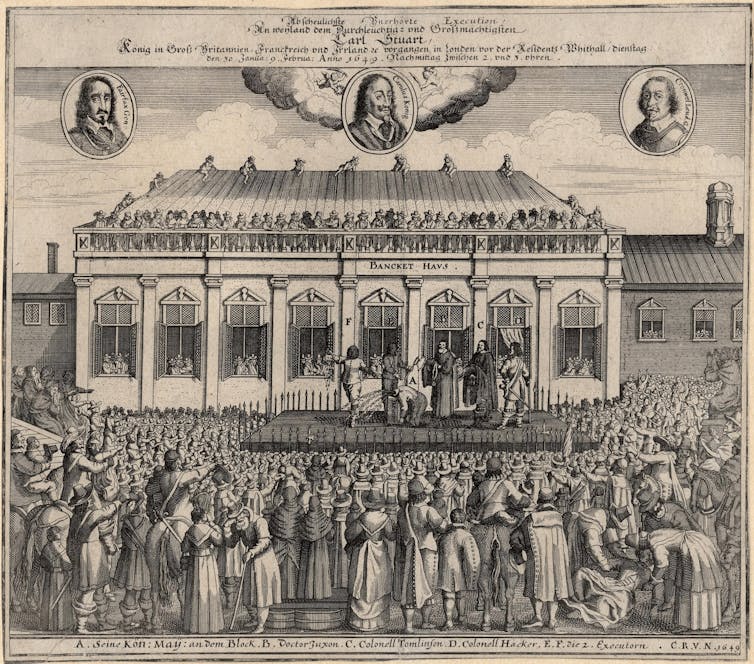

National Portrait Gallery, London, via Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps counterintuitively, it is when outgoing presidents in transitioning democracies enshrine protections against their prosecution directly before leaving office that the democratic system is more likely to endure. This was the case in Chile with dictator Augusto Pinochet, who left power in 1989 under the aegis of a constitution he foisted on the country on his way out.

By contrast, after-the-fact pardoning of crimes – as Gerald Ford did of Richard Nixon – runs the risk of creating a larger threat to democracy: the idea that rogue leaders and their henchmen are above the law. If Trump finds a way to pardon himself, he may reduce his legal vulnerability, but he can’t erase it entirely.

If prosecutors or Congress let Trump off the hook, they may be the ones breaking new and dangerous ground, truly shattering the rule of law that underpins American democracy.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

James D. Long, Associate Professor of Political Science, Co-founder of the Political Economy Forum, Host of “Neither Free Nor Fair?” podcast, University of Washington and Victor Menaldo, Professor of Political Science, Co-founder of the Political Economy Forum, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.