David Caldicott, Australian National UniversityEmergency departments around Australia have experienced COVID in a variety of ways.

From the first quarter of 2020, most if not all have worked hard to plan for an influx of very unwell, highly infectious patients. In the less fortunate of jurisdictions, those apprehensions are being realised — though thankfully not yet to the magnitude seen in some overseas cities.

Hospital emergency departments (EDs) are under intense pressure and there have been calls for the public to carefully weigh up need before presenting there. Don’t come if you don’t need to, they’ve been told. But equally, don’t wait if you need treatment, especially for COVID.

Less staff, more pressure

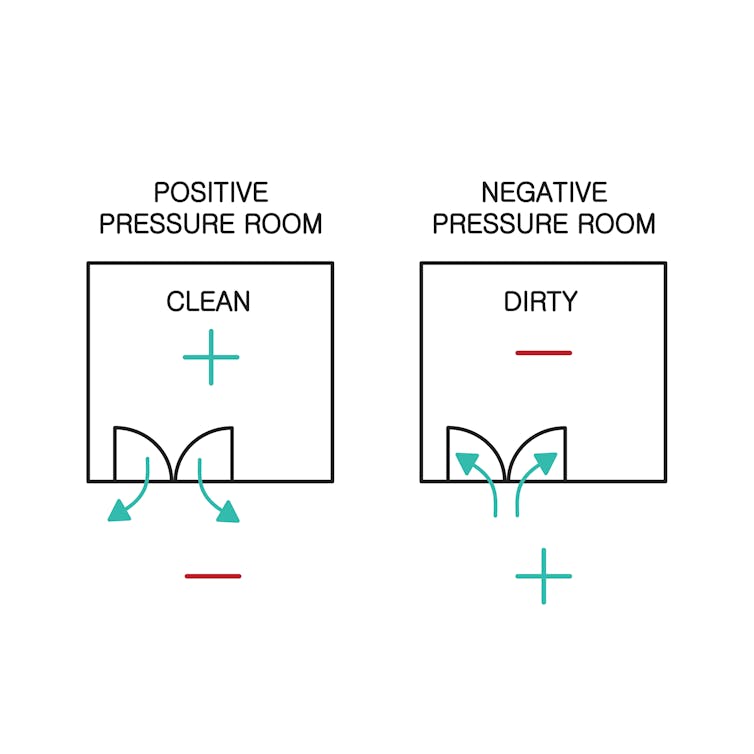

For all hospitals, COVID planning has involved creating streams of patient flow, to ensure those infected can be treated in addition to and at the same time as those who are not — while preventing the former infecting the latter. This is labour-intensive work, often duplicating patient pathways but without a doubling of staff.

In fact, staff numbers in many EDs are down in Australia, for a variety of reasons. Many smaller rural departments rely on fly-in-fly-out locums, now locked out by lockdowns. At times, doctors and nurses have been furloughed because they have been infected at work or elsewhere, or because they have been close contacts.

Understaffed EDs push on, with the greater burden being carried by fewer health workers, resulting in their subsequent burnout. To that, add the task of working in full personal protective equipment, often for many hours at a time. It is physically demanding, uncomfortable, unpleasant work, in an environment in which both high levels of vigilance to keep staff safe and cognitive skills to manage often complex and rapidly deteriorating patients are required.

Read more:

Health workers are among the COVID vaccine hesitant. Here’s how we can support them safely

Not just COVID patients

Much of the focus in the media on health care in a time of pandemic has understandably been on COVID hospitalisations and subsequent intensive care unit admissions. Less has been said about the impact of COVID on the treatment of other illnesses or injuries.

We are very fortunate in Australia there is still more of “the other” in our EDs than there is COVID. That might change in the run up to Christmas.

The ED is most obviously a place of treatment for acute injuries and illnesses. In addition to that, we treat people with chronic illnesses. The ED can act as a safety net for those who have no one else to turn to and reassure many without affliction. For patients in each of these categories, the experience of ED has changed significantly.

There are great concerns many of those who need immediate medical care are deferring seeking it. They may fear catching COVID or being a burden on a strained system. Many in the latter category are elderly patients and those with probably the most reasonable indications for using our services.

Read more:

Here’s what happens when you’re hospitalised with COVID

First off, it’s your emergency

So how should we, as a resource-constrained civil society, in the middle of a pandemic, use our EDs?

The first and overriding principle is that any medical emergency is YOUR emergency. If you think you are experiencing a medical emergency — one you cannot see yourself addressing with the resources available to you, at the time you are experiencing it — you should come to ED. It doesn’t matter if it seems trivial to others, it’s your emergency. And we are your emergency department.

If you don’t feel too unwell, and are uncertain where you should go for medical care, there are alternatives to the ED where excellent medical advice and treatment can be found.

Telehealth has been a godsend to both patients and our GP colleagues. There are now also numerous health lines to call. Pharmacists can provide excellent information about medication, as well as now providing COVID vaccinations.

The ED is not the best place to go to have a COVID test. If you are otherwise well, there are many testing locations where you will wait a far shorter time for a test and the results.

Similarly, many concerns about the very rare side effects of COVID vaccination can be addressed with a telehealth consultation and a blood test if required.

Read more:

How COVID affects the heart, according to a cardiologist

Extra precautions, longer waits

If you do come to the ED, try and be patient. There are extra measures in place to keep you safe.

You’ll need to wear a mask and check in with a QR code, use hand sanitiser and physically distance. There are increasingly strict rules about the numbers of visitors.

If that’s a problem, you’re probably going to be asked to leave. It’s nothing personal — we have a duty of responsibility to all our patients.

You might wait longer than expected despite the efforts of medical staff to see everyone as quickly as possible.

EDs treat all comers

Finally, if you’re worried about the consequences of catching COVID, get vaccinated. We treat all comers, with a variety of beliefs about their medical care — all as long as they agree to abide by the rules of “The House”: to be respectful and abide by hospital procedures.

But vaccination will reduce your chance of needing ED attention as a consequence of COVID — and protect you from catching it if you come to ED for another reason.

Working in the ED at the moment isn’t much fun for anyone. We’re all really tired and, for many, that’s even before the ED where we work has become COVID-dominant. We’re looking forward to moving out of this phase of the pandemic, safely. Then we can get back to treating the mishaps of more normal human lifestyles, led to the fullest.

Read more:

How well do COVID vaccines work in the real world?

![]()

David Caldicott, Senior lecturer, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.