Kate Griffiths, Grattan Institute; Danielle Wood, Grattan Institute, and Tom Crowley, Grattan Institute

Political parties in Australia collectively received $168 million in donations for the financial year 2019-20. Today, Australians finally get to see where some of the money came from with the release of data from the Australian Electoral Commission.

While the big donors will make the headlines, they are only the tip of the iceberg. More than half of the funding for political parties remains hidden from public view. And that is exactly how the major parties want it.

What does the data tell us?

The Coalition and Labor received more in donations than all other parties combined. The Coalition received 41% of all funds (or A$69 million), while Labor received 33% ($55 million). The Greens came a distant third at 11% ($19 million), bumping Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party out of the position it held during the 2019 election.

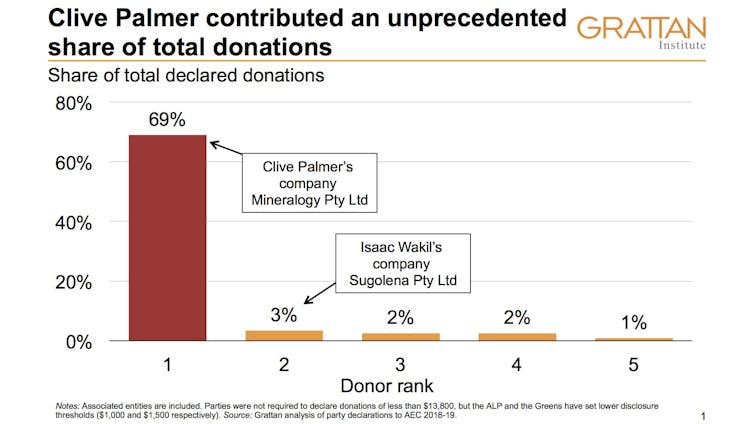

The largest 5% of donors accounted for half of declared donations. For the second year in a row, the largest individual declared donation was made by Palmer’s company Mineralogy, which gave $5.9 million to his own party.

The Coalition’s largest donor, Richard Pratt’s Pratt Holdings, donated $1.5 million. Other major donations to the Coalition included the Greenfields Foundation ($450,000), an investment company linked to the Liberal Party; and Transcendent Australia ($203,000), a company owned by Chinese businesswoman Sally Zou.

Unsurprisingly, many of Labor’s largest donors are unions, led by the “Shoppies” union (the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association, or SDA), which donated almost $500,000. Labor also received large donations from fundraising vehicles associated with the party, including Labor Holdings Pty Ltd, which donated $910,000.

Read more:

Eight ways to clean up money in Australian politics

Other large donors are bipartisan givers. The Australian Hotels Association gave $154,000 to the Coalition and $271,000 to Labor. Woodside Energy gave $198,000 to the Coalition and $138,000 to Labor. The Macquarie Group (including Macquarie Telecom) gave $254,000 to the Coalition and $184,000 to Labor. ANZ continued its regular donations to both sides with $100,000 each.

Total donations were smaller than the previous year (an election year). But those who donate “off-cycle” can still have substantial influence, whether they are political devotees, or playing the “long game” of using donations to open doors and wield political influence.

But a lot of the money remains hidden from public view

Declared donations are only a fraction of the total money flowing to our political parties.

Out of $168 million in party funding, only $15 million of donations were declared (or just 9%). Another $59 million — around one-third — is public funding provided by electoral commissions.

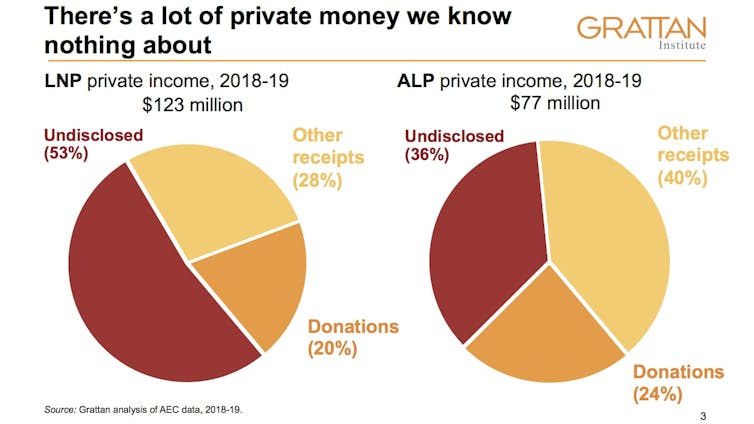

The rest? A murky combination of undeclared donations and a messy bucket of funds called “other receipts”, which includes everything from investment income to money raised at political fundraising dinners. This chart shows the breakdown for the two major parties.

More than half of the Coalition’s private funding is undisclosed, and 40% of Labor’s funds. This rises to about 90% across both parties when other receipts are included.

The major parties want it this way

The Commonwealth donations disclosure regime is incredibly weak compared to almost all Australian states and most other advanced nations. Let’s be clear: this is a political choice backed in by the major parties.

In December, both major parties rejected a bill introduced by crossbench Senator Jacqui Lambie to improve transparency of political donations. It wasn’t revolutionary — the bill didn’t ban donors, or limit donations, or restrict what parties could do with donations. It simply proposed giving the public more and better information on the major donors, including:

-

requiring donations over $5,000 to be declared by the parties (the current threshold is $14,300)

-

stopping “donations splitting”, in which a major donor can hide by splitting a big donation into a series of small ones

-

making income from political fundraising events declarable

-

publishing data about donations within weeks (rather than the current eight to 19 months).

Yet, the bill was whitewashed. The committee rejected it on the basis that “there is already an effective regime in place”.

Our current system doesn’t have the balance right

The Commonwealth donations disclosure regime is supposed to provide transparency and to “inform the public about the financial dealings of political parties, candidates and others involved in the electoral process”. But it clearly does not deliver on this in its current form.

There is a balance to be drawn between the interests of donors in protecting their privacy and the interests of the public in knowing who funds and influences political parties.

Read more:

A full ban on political donations would level the playing field – but is it the best approach?

But it is very hard to see how the current system – which keeps the majority of private money out of public view and unnecessarily delays the release of all donation data – has got the balance right.

A good disclosure system would close the loopholes that allow major donors to hide, while protecting the privacy of small donors.

Australians consistently say that they are suspicious that politicians are corrupt and that governments serve themselves and their mates rather than the public interest. Perhaps they’re right. Today’s donations release reminds us of the shortfalls of a system designed for donor and party interests over the public interest.![]()

Kate Griffiths, Fellow, Grattan Institute; Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute, and Tom Crowley, Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.