paintings/Shutterstock

Elisa Palazzo, UNSW; Annette Bardsley, University of Adelaide, and David Sanderson, UNSW

First the drought, then bushfires and then flash floods: a chain of extreme events hit Australia hard in recent months. The coronavirus pandemic has only temporarily shifted our attention towards a new emergency, adding yet another risk.

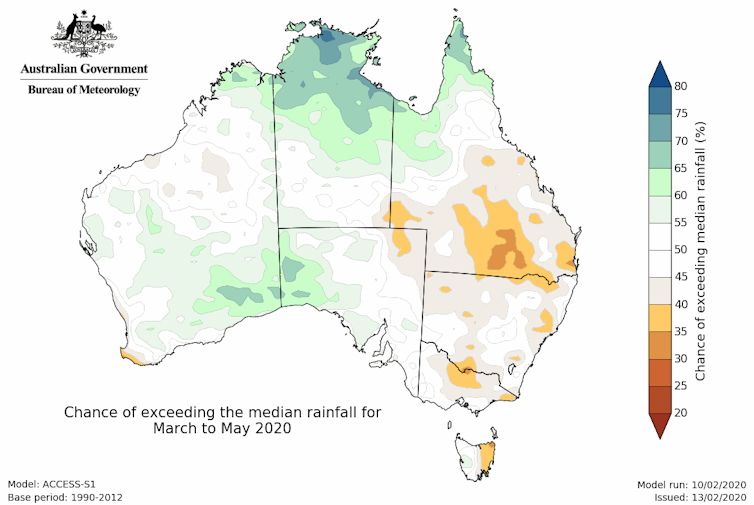

We knew from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that the risk of extreme events was rising. What we perhaps didn’t realise was the high probability of different extreme events hitting one after the other in the same regions. Especially in the fringes of Australian cities, residents are facing new levels of environmental risk, especially from bushfires and floods.

Read more:

Some say we’ve seen bushfires worse than this before. But they’re ignoring a few key facts

But this cycle of devastation is not inevitable if we understand the connections between events and do something about them.

Measures to slow climate change are in the hands of policymakers. But, at the adaptation level, we can still do many things to reduce the impacts of extreme events on our cities.

We can start by increasing our capacity to see these phenomena as one problem to be tackled locally, rather than distinct problems to be addressed centrally. Solutions should be holistic, community-centred and focused on people’s practices and shared responsibilities.

Respond to emergency

We can draw lessons from humanitarian responses to large disasters, including both national and international cases. A recent review of disaster responses in urban areas found several factors are critical for more successful recovery.

One is to prioritise the needs of people themselves. This requires genuine, collaborative engagement. People who have been through a bushfire or flood are not “helpless victims”. They are survivors who need to be supported and listened to, not dictated to, in terms of what they may or may not need.

Another lesson is to link recovery efforts, rather than have individual agencies provide services separately. For instance, an organisation focusing on housing recovery needs to work closely with organisations that are providing water or sanitation. A coordinated approach is more efficient, less wearying on those needing help, and better reflects the interconnected reality of everyday life.

In the aid world this is known as an “area-based” approach. It prioritises efforts that are driven by people demand rather than by the supply available.

A third lesson is give people money, not goods. Money allows people to decide what they really need, rather than rely on the assumptions of others.

As the bushfires have shown, donations of secondhand goods and clothes often turn into piles of unwanted goods. Disposal then becomes a problem in its own right.

Read more:

How to donate to Australian bushfire relief: give money, watch for scams and think long term

Combining local knowledge and engagement

Planning approaches in outer urban areas should be realigned with our current understanding of bushfire and flood risk. This situation is challenging planners to engage with residents in new ways to ensure local needs are met, especially in relation to disaster resilience.

In areas of high bushfire risk, planning needs to connect equally with the full range of locals. Landscape and biodiversity experts, including Indigenous land managers, and emergency managers should work in association with planning processes that welcome input from residents. This approach is highly likely to reduce risks.

Planners have a vital job to create platforms that enable the interplay of ideas, local values and traditional knowledge. Authentic engagement can increase residents’ awareness of environmental hazards. It can also pave the way for specific actions by authorities to reduce risks, such as those undertaken by Country Fire Service community engagement units in South Australia.

Read more:

Rebuilding from the ashes of disaster: this is what Australia can learn from India

Managing water to build bushfire resilience

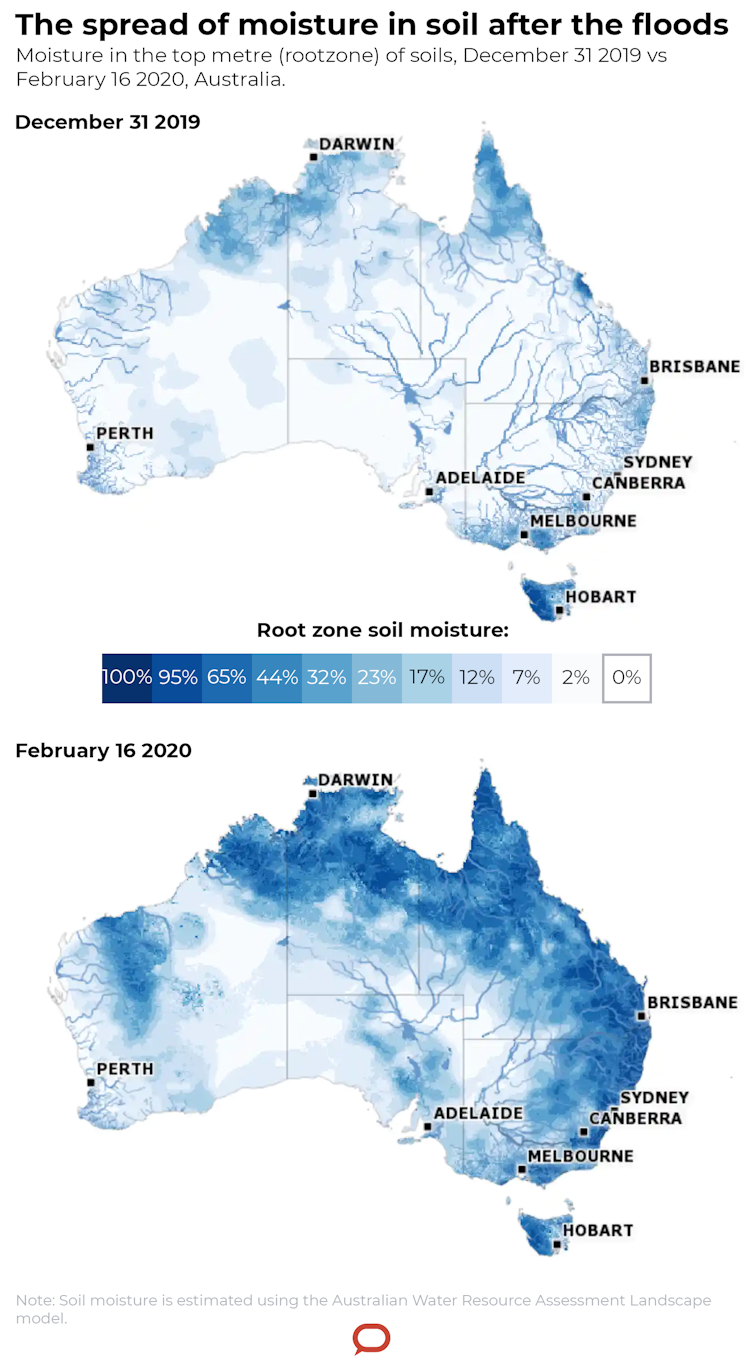

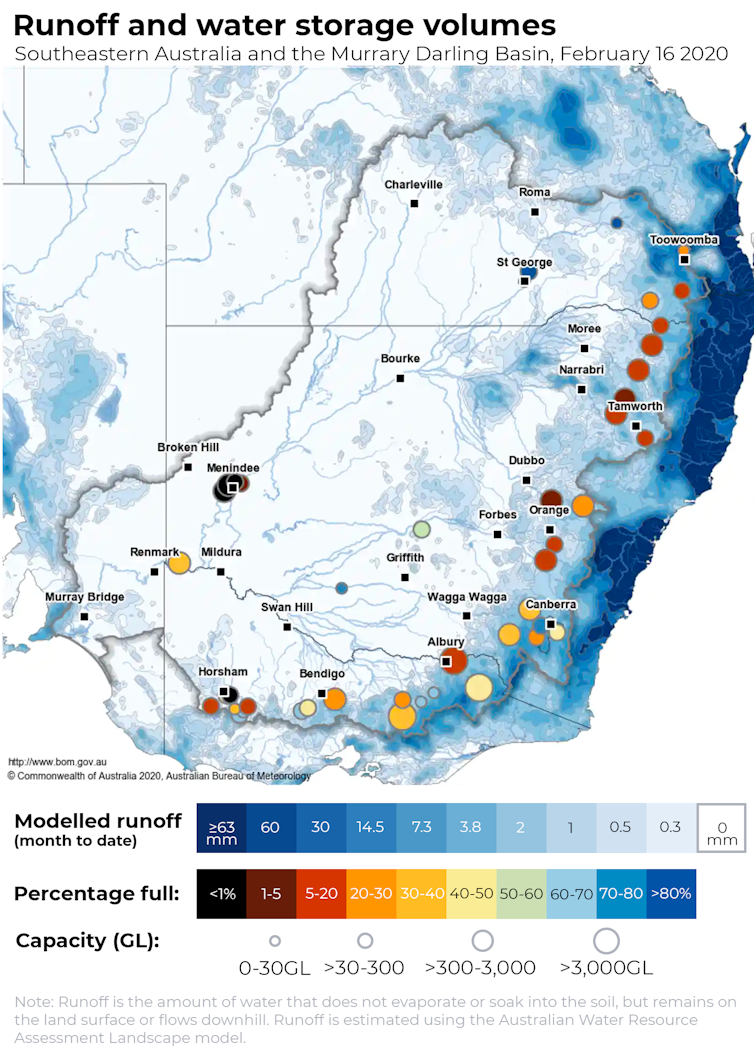

Regenerating ecosystems by responding to flood risk can be crucial to increase urban and peri-urban resilience while reducing future drought and bushfire impacts.

Research on flood management suggests rainwater must be always seen as a resource, even in the case of extreme events. Sustainable water management through harvesting, retention and reuse can have long-term positive effects in regenerating micro-climates. It is at the base of any action aimed at comprehensively increasing resilience.

Read more:

Design for flooding: how cities can make room for water

In this sense, approaches based on decentralised systems are more effective at countering the risks of drought, fire and flood locally. They consist of small-scale nature-based solutions able to absorb and retain water to reduce flooding. Distributed off-grid systems support water harvesting in rainy seasons and prevent fires during drought by maintaining soil moisture.

Decentralisation also creates opportunities for innovation in the management of urban ecosystems, with responsibility shared among many. Mobile technologies can help communities play an active role in minimising flood impacts at the small scale. Information platforms can also help raise awareness of the links between risks and actions and lead to practical solutions that are within everybody’s reach.

Tailor responses to people and ecosystems

Disrupted ecosystems can make the local impacts of drought, fire and flood worse, but can also play a role in global failures, such as the recent pandemic. It is urgent to define and implement mechanisms to reverse this trend.

Lessons from disaster responses point towards the need to tailor solutions to community needs and local environmental conditions. A few key strategies are emerging:

-

foster networks and coordinated approaches that operate across silos

-

support local and traditional landscape knowledge

-

use information platforms to help people work together to manage risks

-

manage water locally with the support of populations to prevent drought and bushfire.

Recent environmental crises are showing us the way to finally change direction. Safe cities and landscapes can be achieved only by regenerating urban ecosystems while responding to increasing environmental risks through integrated, people-centred actions.![]()

Elisa Palazzo, Urbanist and landscape planner – Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Built Environment, UNSW; Annette Bardsley, Researcher, Department of Geography, Environment and Population, University of Adelaide, and David Sanderson, Professor and Inaugural Judith Neilson Chair in Architecture, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.