Richard Holden, UNSWIn other circumstances Treasurer Josh Frydenberg might be dancing a jig.

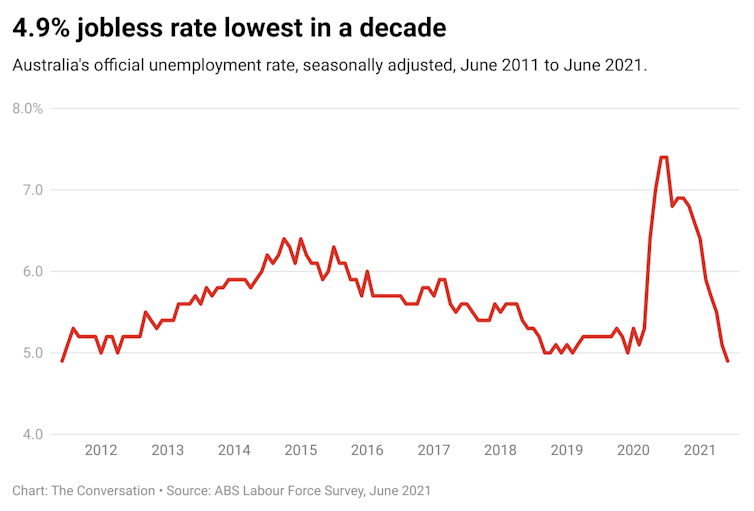

But the pall of the Greater Sydney lockdown, which has now spilled over to Melbourne declaring its fifth lockdown, meant there was no room for smiling yesterday about the latest jobs figures, showing Australia’s unemployment rate in June fell below 5% for the first time in a decade.

The labour force survey data from Australian Bureau of Statistics shows 22,000 fewer Australians were unemployed last month compared to May. This pushed the unemployment rate down to an eye-catching (if not yet eye-popping) 4.9%.

Next month’s figures, of course, are unlikely to be so rosy. But these numbers still enable us to understand the progress the Australian economy is making with a number of important issues predating the COVID crisis.

CC BY-SA

Importantly, the lower unemployment rate wasn’t due to a reduction in labour-force participation — sometimes known as the “giving up effect”, when folks just stop looking for work because they don’t expect to find a job. The participation rate was steady at 66.2%. In fact, the number of employed persons increased by 29,100 to 13,154,200.

There was even good news for younger Australians, with the youth unemployment rate down by 0.5 percentage points to 10.2%. This reflected a strong recovery from the pandemic, being 6.1 percentage points lower than a year ago in June 2020.

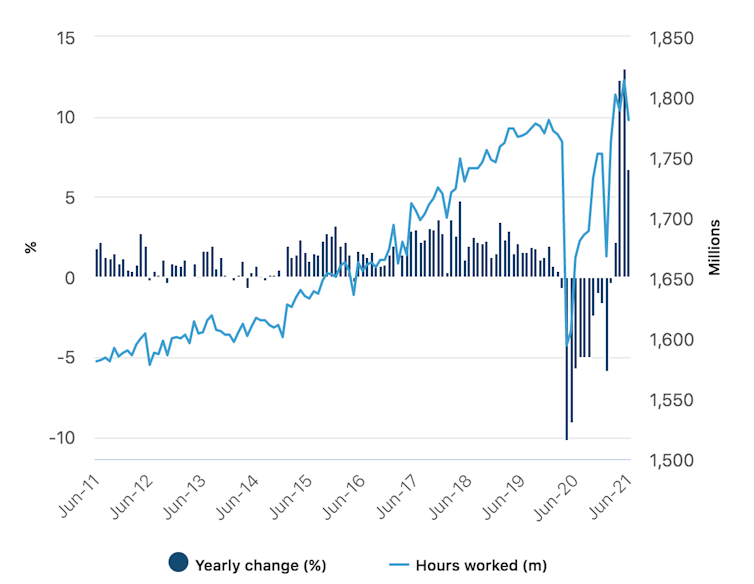

Total hours worked

The one statistic I always focus on is the total hours worked number. This is because the headline unemployment rate, as critics always point out, doesn’t tell us to what extent people are getting enough work.

On this measure there was slightly less good news. Total hours worked in June were down 1.8%, by 33.4 million hours to 1,781 million hours; and that’s seasonally adjusted, so its not just some “winter” thing.

Monthly hours worked in all jobs, seasonally adjusted

ABS Labour Force Survey, June 2021., CC BY-SA

Slow wages growth

In 2019 one could best characterise the Australian economy as barely growing in per-capita terms. Wages growth was stubbornly low, while unemployment and underemployment were unacceptably high.

Having recognised this — too late, mind you, but at least eventually — the Reserve Bank cut interest rates from 1.50% to 0.75% in an effort to get wages up, unemployment down, and inflation back into the central bank’s 2-3% target zone. Inflation has been outside its target band for the entirety of Philip Lowe’s governorship, which began in September 2016.

Read more:

Vital Signs: Why has growth slowed globally? It has something to do with technology

The pandemic pushed the RBA to drive the cash rate close to zero, and also buy government bonds to push down longer-term interest rates.

By looking at where unemployment, underemployment and wages growth stand relative to 2019 levels, we learn something about Australia’s pandemic recovery.

In doing so, we should not lose sight of fact the economy in general — and the labour market in particular — were not in good shape pre-COVID, and policies to address those issues have long been needed.

Edging closer to where we need to be

So, how’s that going? In some sense, pretty well.

June’s 4.9% unemployment rate is the lowest since June 2011. Getting down to something with a “4” in front of it edges Australia closer to reducing the slack in the labour market sufficiently to push wages up.

But the task is certainly not complete.

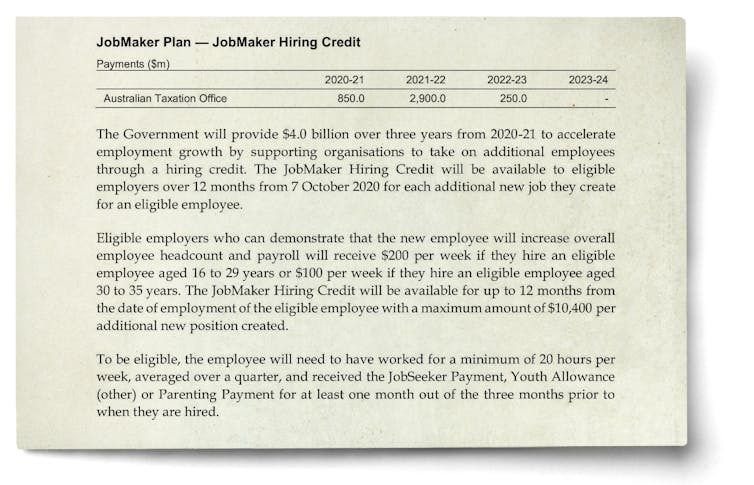

The aggressive monetary policy being used by the RBA and the “Frydenberg pivot” to aggressive fiscal policy at this year’s federal budget are both aimed at reducing unemployment and hence increasing wages.

However, no one really knows how low unemployment needs to get in Australia to getting wages moving again in earnest. The RBA’s official position is maybe 4.5%. Lowe has said it may well be a fair bit lower.

The smart path, arguably, is “let’s find out” — the central bank should keep using monetary policy and the treasury keep using fiscal policy until we see real wages growth at a sustained level. My own guess is that means getting the unemployment rate down to just below 4%.

Read more:

Vital Signs: we’ll never cut unemployment to 0%, but less than 4% should be our goal

Reigniting an immigration debate

The backdrop for these improvements in the labour market is a closed international border. This is likely to become a hot debate — especially since Lowe fired the starter pistol last week by suggesting Australia’s historically high levels of immigration had been helping keep wages low.

Those were rather careless, or at least ill-advised, remarks from the central bank governor, contrary to solid academic evidence pointing the other way.

He may say more on this at a future date — perhaps after some discussion and reflection. But, as he is so fond of saying, “only time will tell”.![]()

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.