Tag Archives: JobMaker

JobKeeper and JobMaker have left too many young people on the dole queue

Kathryn Daley, RMIT University; Belinda Johnson, RMIT University, and Patrick O’Keeffe, RMIT UniversityOf the more than 870,000 Australians who lost their jobs in the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis, 332,200 – or 38% – were young Australians aged 15-24.

By June 2020, as the overall unemployment rate hit 7.4%, the youth unemployment rate spiked to 16.4%, with a further 19.7% underemployed (working fewer hours than they wanted).

As of February the overall unemployment rate had fallen to 5.8%, compared with 5.1% in February 2020. The youth unemployment rate meanwhile was 12.9%, compared with 11.5% the year before, and a further 16% were underemployed.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has enthused about there now being “more jobs in the Australian economy than there were before the pandemic”. But that’s true only for those 25 and older: 77,600 more are employed than before the crisis. For those aged 24 and under, 74,100 fewer have jobs.

Read more:

The successor to JobKeeper can’t do its job. There’s an urgent need for JobMaker II

So clearly the pandemic has hit younger workers the hardest. The reasons for disproportionate impact aren’t complicated. Young people are more likely to work in casual jobs – the first to be excised in hard economic times – and in those sectors most affected by border closures, lockdowns and other measures – retail, hospitality, tourism.

Yet the federal government’s policy responses, injecting billions of dollars into the economy to support businesses and employment, have compounded this impact through deliberate yet flawed policy design.

JobKeeper has kept proportionally fewer young people in jobs. Changes allowing withdrawal of superannuation will hurt them more in the longer term. And JobMaker, the program designed specifically to encourage employment of younger workers, has proven a monumental flop.

Shut out of JobKeeper

The centrepiece of the federal government’s support measures was the A$100 billion JobKeeper program, initially paying a subsidy of $750 a week before tapering and finally being axed at the end of March.

The Reserve Bank of Australia estimates JobKeeper payments kept at least 700,000 workers off the dole queue. But to qualify, employees had to have been working for their employer for a minimum of 12 months.

This disproportionately excluded younger workers – being more likely to be recent workforce entrants, to switch jobs more than older workers, and to be in employed in casual or other forms of insecure work.

To illustrate, Australian Bureau of Statistics data from August 2019 shows young people comprised 17% of the workforce yet accounted for 46% of all short-term casual employees.

Of those employed casually, 26.4% of young people had been with their employer for less than 12 months, compared to 6.5% of those aged 25 and over. So one in four young people employed casually were not eligible for JobKeeper, compared with only one in 16 of their older counterparts.

Read more:

The budget promises jobs, but does little for workers in the gig economy

Drawing down superannuation

JobKeeper’s design thus pushed proportionally more younger workers on to the dole queue. It also likely contributed to more of them dipping into their superannuation savings under the provisions announced by the federal government in March 2020.

Those provisions allowed Australians affected by the economic crisis to withdraw up to $20,000 from their superannuation accounts (in two rounds of $10,000 each – one last financial year, another this financial year).

The Industry Super Australia estimated about 395,000 people under 35 completely drained their super accounts.

This emptying of accounts is not surprising given the average superannuation balance by age 30 is about $28,000 for men and $23,700 for women.

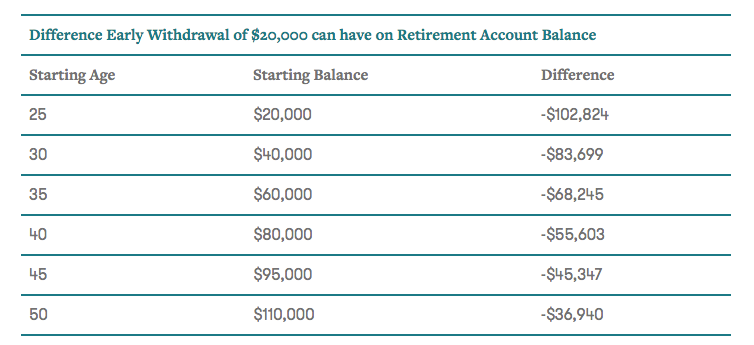

But it means many will have considerably less super to retire on. The long-term cost of a 25 year-old withdrawing $20,000 is more than $100,000, compared with about $37,000 for a 50-year-old, according to estimates by financial comparison site Canstar.

Spend now, lose later

Canstar, CC BY-NC

There’s also evidence the design of the super-access scheme has allowed unnecessary withdrawals. While those taking out money have had to declare they need the money to pay for essential items (such as rent or bills), there has been no scrutiny of this prior to approval.

Indeed, according to credit-scoring company Illion about two-thirds of the funds withdrawn this financial year was spent on discretionary items such as clothing, furniture, restaurants and alcohol.

As former prime minister Paul Keating has put it, the government has relied on individuals “ratting their own savings” to buttress its own stimulus spending.

Read more:

The economy can’t guarantee a job. It can guarantee a liveable income for other work

More work needed

The one program meant to specifically address youth unemployment, the JobMaker Hiring Credit, has so far proven a failure. Its aim is to incentivise employers to hire job seekers aged 16 to35 with a weekly $200 subsidy, creating 450,000 jobs over two years. But in late March, Treasury officials revealed it had so far led to just 609 hires.

All unemployment is costly for individuals, families and the wider community. But high and long-term youth unemployment can have particularly dire consequences that reverberate for decades. It creates the risk of “scarring”, suppressing an individual’s job and income prospects over their entire life. That ultimately requires the government picking up the tab.

Youth unemployment was already a significant issue prior to the COVID crisis. Now, with younger people hit hardest by the pandemic’s economic impacts, it’s imperative to ensure an entire generation is not permanently disadvantaged.![]()

Kathryn Daley, Senior Lecturer & Program Manager – Youth Work and Youth Studies. School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, RMIT University; Belinda Johnson, Lecturer and Program Manager, Social Science (Psychology), School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, RMIT University, and Patrick O’Keeffe, Lecturer, Bachelor of Youth Work and Youth Studies, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The successor to JobKeeper can’t do its job. There’s an urgent need for JobMaker II

workskil/Shutterstock

Renee Fry-McKibbin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; Peter M. Downes, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, and Warwick J. McKibbin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National UniversityUntil the end of last month one million workers were paid by JobKeeper.

This month there are none. Treasury thinks up to 150,000 will lose their jobs.

Credible estimates put the number higher, at as much as one quarter of a million.

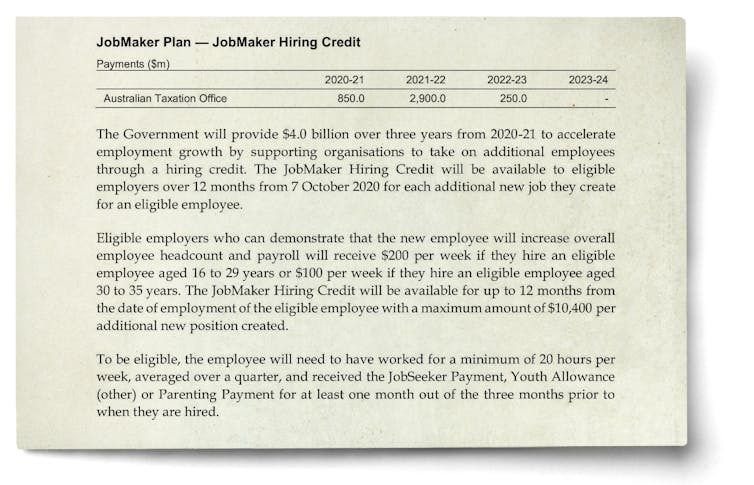

In its place, the government introduced a A$4 billion JobMaker Hiring Credit. It will give employers who can demonstrate that a new employee will increase overall headcount (and payroll) $200 per week if the new hire is aged 16-29, or $100 if the new hire is aged 30-35.

Billions on offer, little takeup

Employers will get nothing for new hires aged 36 and over — no matter how disadvantaged and no matter how suitable.

The scheme hasn’t got off to a good start. It is reported to have had only 609 applications in its first seven weeks.

The October budget said it would attract 450,000 applications, creating 45,000 jobs.

The low takeup isn’t surprising.

Evidence shows when unemployment is high, the best way to target disadvantaged groups (such as young jobseekers) is not to target them, but to target high employment growth more broadly.

High employment growth disproportionately helps less-advantaged workers because they are further down the hiring queue.

The $4 billion appropriated for JobMaker is still available to be spent. If spent well, it would help consolidate what so far has been a very solid recovery.

Read more:

JobMaker is nowhere near bold enough. Here are four ways to expand it

But it needs to be simplified. JobMaker II could be set up as a tax rebate on the quarterly increase in firms’ payrolls, say 60% on any increment above 6%.

Firms that were on JobKeeper in the March quarter (its final quarter) would be allowed to deduct their JobKeeper receipts from their payroll in estimating the starting point for the calculation.

JobMaker II could save 100,000 jobs

If those firms retained their workers (and the rebate was set at 60% on any increase in payroll beyond 6%) they would receive a little over half their March quarter JobKeeper payment in the June quarter.

Most of the money would go to firms and disadvantaged workers who still need it.

The ordinary job matching process would be allowed to work, without some jobseekers being given preference over others because of factors such as their age.

And firms already thriving would have an incentive to increase their employment by even more.

But it should be announced this week

The proposal would have to be implemented quickly to maintain the momentum established by JobKeeper. With JobMaker as it is, it will slip away.

The main thing required is for the treasurer to make an announcement setting out the broad outlines.

Anderson Guerra/Pexels

The week after Easter is a time when business owners will be taking stock – working out whether they can afford to continue to carry workers who until the end of March were supported by JobKeeper.

Our modelling suggests that refashioning JobMaker along the lines we have suggested could save and generate 100,000 to 130,000 jobs over the next six months.

It would keep employment 1% higher than it would have been, generating higher wage growth and higher tax revenue leading to a lower budget deficit.

With interest rates close to zero, the employment effect would be sustained.

The impacts would be greatest for young and for low-skilled workers, with the bulk of the benefits flowing to wages rather than profits (as regrettably happened in high profile cases as a result of JobKeeper).

And without the discrimination implicit in age targeting, other genuinely disadvantaged groups, including low-income women over 35, would be better off.

Those women would be in a better position to build their superannuation balances and be less exposed to homelessness.

Read more:

In defence of JobMaker: not perfect, but much to like

The economy seems on track for a rapid recovery. But with the pandemic continuing and the outlook uncertain, it’d be wise to take out insurance.

With interest rates low, even a more expensive JobMaker II would pay for itself.![]()

Renee Fry-McKibbin, Professor of Economics, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; Peter M. Downes, Research Associate, Centre for Climate and Energy Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, and Warwick J. McKibbin, Chair in Public Policy, ANU Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis (CAMA), Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In defence of JobMaker, the replacement for JobKeeper: not perfect, but much to like

Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

There’s a lot to like about the JobMaker Hiring Credit announced in the budget.

As lockdowns ease, it’s logical to cautiously move from protecting jobs in struggling sectors to generating new jobs in growing ones.

For the next year, employers who take on a new worker who has been on JobSeeker or a related benefit will receive A$200 per week for up to 12 months if the worker is aged 16 to 29 years, or $100 per week if aged 30 to 35 years.

The employer will have to demonstrate that the new worker will increase overall

headcount and payroll, and the payment will top out at $10,400 per position.

The budget says it will support 450,000 jobs.

Many will simply be brought forward, created earlier than they would have been; but this itself should be helpful, contributing to a virtuous cycle of employment, confidence, and consumer demand.

Past experience suggests that about 10% will be truly additional – jobs that wouldn’t have been created without the subsidy.

Cheaper per job than tax cuts

But even then, unlike the personal tax cuts, which the Australian Council of Social Service believes will cost $475,000 per job created, the cost per job would be a more modest $80,000.

More importantly, the hiring credit could prompt employers to take on people they might not otherwise have considered – those facing prolonged unemployment.

It is likely that by next year, more than a million people will be on unemployment payments for over a year – three times the peak in long-term unemployment after the early-90s recession.

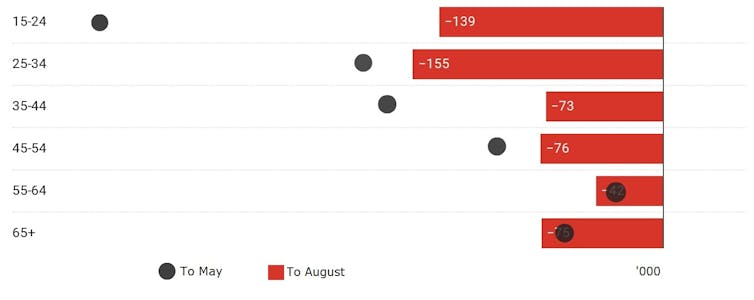

Young people – those under 35 – have been targeted because they lost far more jobs in this recession than older people.

Employment by age, change since February 2020

Source: ABS, RBA

Limited work experience and qualifications means many young people will find themselves out of paid work for a long time.

But they’re not the only ones. There are already over 600,000 people long-term unemployed on benefits for more than a year, most of whom are over 40. Older unemployed people are right to be concerned the wage subsidy might encourage employers to overlook them for younger applicants.

Room for improvement

It’d be better to also target the subsidy to the duration of unemployment; for example to young people unemployed for six months, and others out of paid work for at least a year.

Otherwise a large and diverse set of talents might be wasted.

The subsidies might also be too low. $200 per week is around a quarter of the full-time minimum wage, enough to encourage employers to expand entry-level jobs of around 20 hours a week but perhaps not enough to encourage employers to expand full-time jobs.

Read more:

Budget 2020: promising tax breaks, but relying on hope

This could hasten the shift already under way from fulltime to part-time employment in entry-level jobs in retail, hospitality and other industries. That might reduce unemployment in the short-term, but at the expense of entrenching higher levels of under-employment (people lacking the paid working hours they need).

Another issue is administration. An employment service on the ground would be better at matching the needs of workers and employers and organising pre-vocational training than workers and employers left to their own devices.

It’ll be important to avoid abuses

That could also help ensure the integrity of the scheme. Wage subsidy schemes give rise to concerns that existing workers may be displaced, or that people could be laid off when the subsidy ends regardless of their performance.

Guaranteeing the integrity of the scheme will be vital to ensure it’s fair to all involved and to sustain public support for it.

JobMaker is a welcome innovation, the logical next step after JobKeeper.

If, together with a scaling up of existing wage subsidy schemes, it generates full and part-time jobs for people of all ages who would otherwise be left behind, it could make a real difference.![]()

Peter Davidson, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australian economy must come ‘out of ICU’: Scott Morrison

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

Scott Morrison says it is vital to get the Australian economy “out of ICU” and “off the medication” of government support “before it becomes too accustomed to it”.

In speech on his government’s plans to reset economic growth over the next three to five years, Morrison says, “We must enable our businesses to earn our way out of this crisis.

“That means focusing on the things that can make our businesses go faster.”

Part of the address, to the National Press Club, has been released ahead of its Tuesday delivery.

Morrison’s strong emphasis on business leading the recovery further sets up the contrast with Anthony Albanese, who has outlined an agenda placing much more stress on the role of government.

The Prime Minister outlines principles that will guide the pursuit of a “JobMaker plan for a new generation of economic success”.

This speech deals with skills and training – flagging extra federal resources would be available for a better system – and with industrial relations (although the IR section hasn’t been released). Morrison has previously flagged he would like a compact involving employers and unions to promote change.

Areas including tax reform, deregulation, energy and federation will be addressed later.

Morrison says the reset’s overwhelming priority “will be to win the battle for jobs”, with the October budget important in this.

He paints a dark background against which the budget will be framed, including “an historic deficit”, debt above 30% of GDP, unemployment about 10% and global trade expected to fall by up to a third.

Five principles will guide the JobMaker plan.

First, Australia will “remain an outward-looking, open and sovereign trading economy”, that won’t “retreat into the downward spiral of protectionism” – but also won’t trade away its values for short term gain.

The second principle “is caring for country, a principle that indigenous Australians have practiced for tens of thousands of years”.

This involves “responsible management and stewardship of what has been left to us to sustainably manage for current and future generations. We must not borrow from future generations what we cannot return to them.

“This is as much true for our environmental, cultural and natural resources as it for our economic and financial ones. Governments must live within their means, to not impose impossible debt burdens on future generations.”

The third principle is leveraging and building on strengths.

These include “an educated and highly-skilled workforce that supports not just a thriving and innovative services sector, but a modern and competitive advanced manufacturing sector.

“Resources and agricultural sectors that can both fuel and feed large global populations, including our own and support vibrant rural and regional communities. A financial system that has proved to be one of the most stable and resilient in the world.

“World leading scientists, medical specialists, researchers and technologists. An emerging space sector.”

Fourthly, “ we must always ensure that there is the opportunity in Australia for those who have a go, to get a go”.

Under this falls “access to essential services, incentive for effort and respect for the principles of mutual obligation. All translated into policies that seek not to punish those who have success, but devise ways for others to achieve it.”

And fifthly is “doing what makes the boat go faster”.

“To strengthen and grow our economy, the boats we need to go faster are the hundreds of thousands of small, medium and large businesses that make up our economy and create the value upon which everything else depends.”

To go faster, businesses need skilled labour, affordable and reliable energy, research and technology they can use, investment capital and finance, markets, and economic infrastructure.

Also relevant are the amount of government regulation they must comply with, and the level and efficiency of the taxes they have to pay, in particular whether these encourage them to invest and employ people.

Morrison says changing the skills and training system will be a priority, to better prepare people for the jobs businesses will create.

Present arrangements are too clunky and unresponsive, he says. Clear information is lacking about the skills needed now and in the future, so the right training and funding can be provided. There are inconsistencies and incoherence in the funding arrangements, with little accountability back to outcomes.

Changes are required to:

-

better link funding to forward looking skills businesses need

-

simplify the system, with greater consistency between jurisdictions and between VET and higher education

-

increase the transparency of funding and the monitoring of performance

-

better coordinate the subsidies, loans and other funding sources, to make the most of the support provided.

“Our national hospital agreement provides a good model for the changes we need to make. Incorporating national efficient pricing for training and activity based funding models would be a real step forward,” Morrison says.

“That is a system my government would be prepared to invest more in.”![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.