Alex Collie, Monash UniversityVictoria’s occupational health and safety regulator, Worksafe, has charged the state’s health department with 58 breaches for failing to provide hotel quarantine staff with a safe workplace.

The breaches occurred between March and July 2020, and at up to A$1.64 million per breach, could amount to fines of $95 million.

This should serve as a warning to all employers to start assessing their workers’ safety against COVID and how they can mitigate these risks, ahead of the nation reopening.

Remind me, what is Worksafe?

States and territories have responsibility for enforcing laws designed to keep people safe at work: occupational health and safety (OHS) laws.

Worksafe Victoria is responsible for and regulates OHS in Victoria. It’s responsible for making sure employers and workers comply with OHS laws; and it provides information, advice and support.

Victoria’s parliament has given Worksafe the power to prosecute employers if they breach OHS laws. In 2018-19, it commenced 157 prosecutions which resulted in nearly A$7 million in fines.

Unlike some other state OHS regulators, Worksafe also manages the Victorian workers’ compensation system.

Why did Worksafe charge the health department?

Worksafe charged Victoria’s Department of Health with 58 breaches of sections 21 and 23 of the Victorian Occupational Health and Safety Act.

The Act requires employers to maintain a working environment that is “safe and without risks to health” of employees. These obligations extend to independent contractors or people employed by those contractors.

Worksafe is alleging that in operating the Victorian COVID-19 quarantine hotels between March and July 2020, the Department of Health failed to maintain a working environment that was safe and limited risks to health, both to its own employees and to other people working in the hotels.

Essentially Worksafe is stating that through a series of failures, the department placed government employees and other workers at risk of serious illness or death through contracting COVID-19 at work.

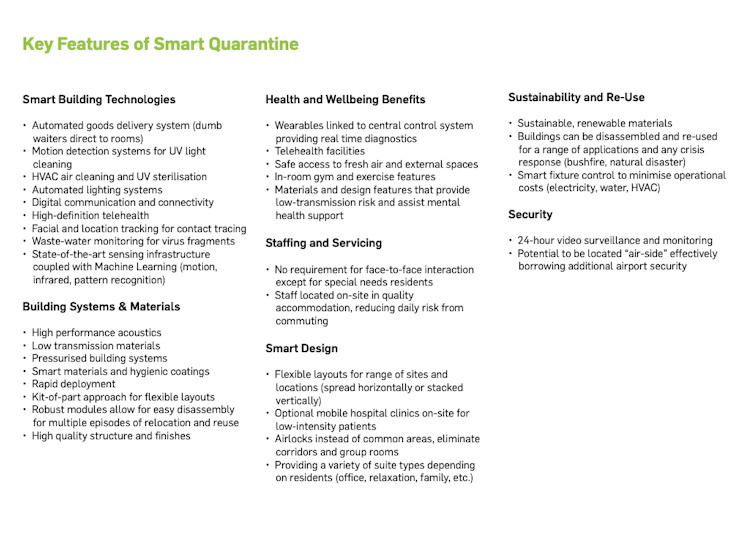

Worksafe alleges the Victorian health department failed to:

- appoint people with expertise in infection control to work at the quarantine hotels

- provide sufficient infection prevention and control training to security guards working in the hotels, as evidence shows training can improve employees’ safety practices

- provide instructions, at least initially, on how to use personal protective equipment, and later did not update instructions on mask wearing in some of the quarantine hotels.

Worksafe undertook a 15-month long investigation, beginning in about July 2020. It’s possible the trigger for this investigation was a referral from the Coate inquiry into hotel quarantine, but that has not been stated.

Is it unusual for a government regulator to fine a government department?

It’s not that unusual. Government departments are subject to the same OHS laws as other employers in the state, and so Worksafe’s powers extend to them as well.

In the past few years, Worksafe has successfully prosecuted the Department of Justice, Parks Victoria and the Department of Health, resulting in fines and convictions.

In 2018, for example, Worksafe prosecuted Corrections Victoria (part of the Department of Justice) after a riot at the Metropolitan Remand Centre in 2015 that put the health and safety of staff at risk.

The riot occurred after the introduction of a smoking ban in prisons. Worksafe considered prisoner unrest was predictable and its impact on staff could have been reduced by having additional security in place in the days leading up to the smoking ban.

In that case the Department of Justice pleaded guilty and was convicted and fined A$300,000 plus legal costs.

What does this mean for other employers?

This case highlights that employers have obligations to provide safe working environments for their staff, and other people in their workplaces. This extends to reducing risks of COVID-19 infection.

These obligations don’t just apply to government departments. They apply to every employer in the state.

Employers should ensure they have appropriate systems and policies in place to reduce COVID-19 infection risk to their staff. This includes, where appropriate, physical distancing, working from home, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), good hygiene practices, workplace ventilation, and so on.

Employers should consider the risks unique to their environment and address them appropriately, in advance of the nation reopening when we reach high levels of COVID vaccination coverage.

Some employers in high-risk settings – such as health care, retail and hospitality – will need to do more to protect their workers than others.

What happens next for the Vic health department?

The case has been filed in the Magistrates court, with an initial hearing date set for October 22. It will progress through the court system from there. Most prosecutions are heard in the Magistrates Court although some proceed to the County Court.

If the Department of Health pleads guilty, the courts will determine if a fine should be paid and how much. The court may also determine if a conviction is recorded.

Read more:

Soon you’ll need to be vaccinated to enjoy shops, cafes and events — but what about the staff there?

![]()

Alex Collie, Professor and ARC Future Fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.