Category Archives: flooding

Floods in Germany

Double trouble: floods and COVID-19 have merged to pose great danger for Timor-Leste

Antonio Dasiparu/EPA

Mark Quigley, The University of Melbourne; Andrew King, The University of Melbourne; Brendan Duffy, The University of Melbourne; Claire Vincent, The University of Melbourne; Ian Rutherfurd, The University of Melbourne; Januka Attanayake, The University of Melbourne, and Lisa Palmer, The University of MelbourneTimor-Leste is reeling after heavy rain caused severe floods and landslides over the Easter weekend, killing at least 42 people. Rates of COVID-19 in Timor-Leste are also on the rise. Together, these hazards threaten to interact with deadly consequences.

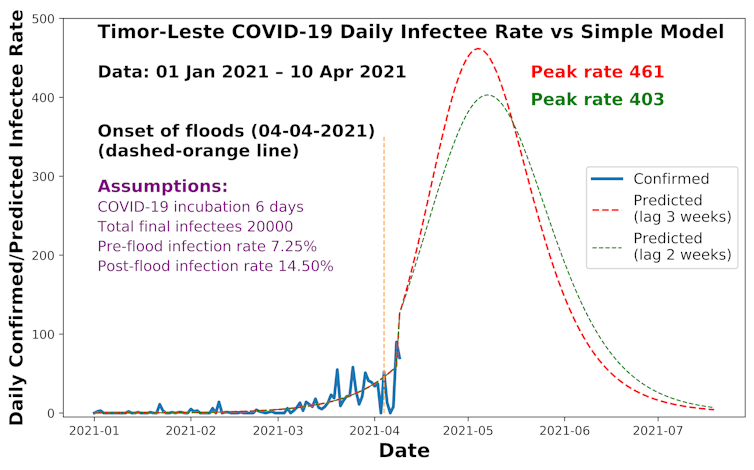

Our research has assessed the likelihood of natural hazards coinciding with, and influencing, the COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, we found temporary relaxations of COVID-19 restrictions during natural disasters are likely to cause large spikes in infection rates.

In Timor-Leste’s capital Dili, the floods and the pandemic have combined to form a dangerous dynamic. Flood damage prompted authorities to temporarily lift COVID-19 restrictions. Evacuees are gathered in group shelters where social distancing may be challenging. Flooding cut power to some COVID treatment centres and put extra pressure on Timor-Leste’s health system.

The situation offers lessons for other populated, flood-prone cites battling the COVID-19 pandemic. Natural hazards will, of course, persist throughout the pandemic. Better understanding the complex interactions between double disasters will help societies and systems become more resilient.

Antonio Dasiparu/EPA

Dili: a recipe for disaster

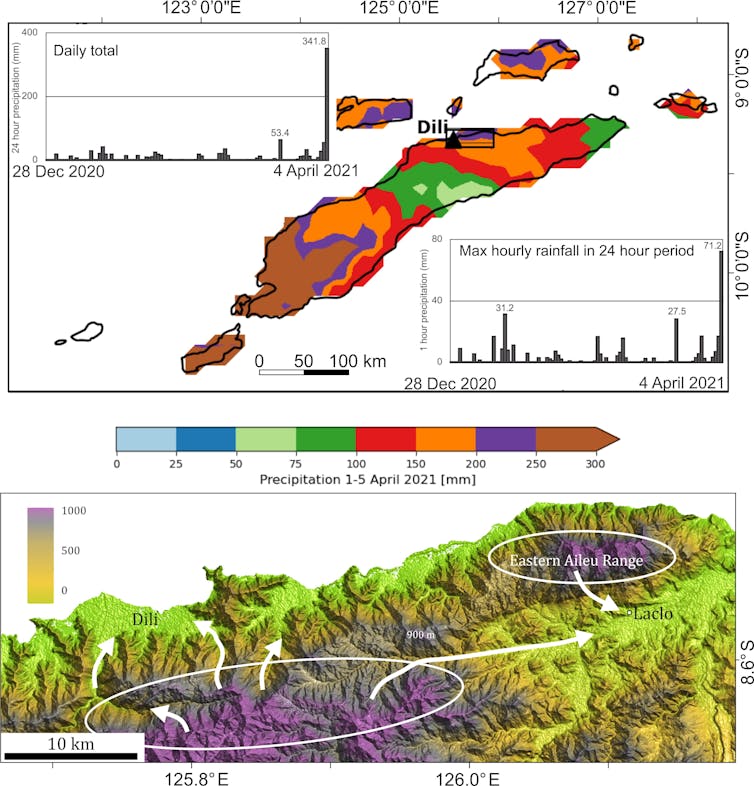

On April 3 and 4, more than 400mm of rain was recorded in Dili. Floodwater and debris washed into populated areas. Recent reports indicate at least 42 people died and 13,554 were displaced. Nearby Indonesian islands were also hit and at least 130 deaths were reported.

Several natural and human factors combine to make Timor Leste vulnerable to flooding.

The country’s mountainous topography (see image below) encourages rainfall and creates steep stream systems that rapidly transfer floodwater into adjacent populated areas. Weak rocks and steep catchments are highly susceptible to landslides.

Read more:

Cyclone Seroja just demolished parts of WA – and our warming world will bring more of the same

Flowing water interacts with the mountains, causing sediment to accumulate in the shape of a fan or cone. This directs flood waters and sediment into central Dili. Also, rampant deforestation and development has increased soil erosion and stream discharge during heavy rain.

Rapid and largely uncoordinated population growth, particularly in Dili, has concentrated vulnerable populations into flood plains and low-elevation coastal areas highly exposed to flooding.

Other factors increasing the flood risk in Dili include:

- concrete structures that don’t allow water to sink into the ground

- multi-pylon concrete bridges that trap flood debris

- urban drainage channels choked with sediment and urban waste.

More broadly in the region, three climate features combined to create ideal conditions for the recent high rainfall and tropical storms: the West Pacific Monsoon, the Madden Julian Oscillation and a La Niña

The COVID combination

Dili is frequently hit by large floods – most recently in March 2020. But this time, the disaster coincided with an escalation in Timor Leste’s COVID-19 infection rate.

In late March this year, the number of new daily cases in Timor-Leste was rising quickly. On April 10, there were 70 new daily cases, bringing the total confirmed cases to more than 1,000.

Even without these twin disasters, many in Timor-Leste already lacked access to medical services and lived below the poverty line. COVID-19 restrictions exacerbated food shortages and poverty.

Then the floods hit. They left thousands homeless with severely restricted access to food and clean water. Roads and bridges collapsed. Crops were destroyed and firewood collection – essential for cooking – has been difficult in some areas.

The floods disrupted a COVID-19 lockdown in Dili, and forced people into crammed refuge centres. Flooding of a national medical storage facility damaged supplies. The national laboratory also flooded and a COVID-19 isolation facility was temporarily evacuated.

During floods, the risks of waterborne and vector-borne disease outbreaks increases. Should this occur, Timor-Leste’s fragile health system would be under even greater pressure.

The first batch of COVID-19 vaccines arrived in Timor Leste on April 5 and the vaccination program has managed to operate despite the flood-related challenges.

Antonio Dasiparu/EPA

A global problem

Many global cities are vulnerable to multiple interacting hazards like those now faced by Timor-Leste. Our analysis suggests 16 of the world’s 20 most populous cities, comprising 5% of the world’s population, have similar geology, population density and/or land use to Dili and could face similar multiple disasters. These cities include Jakarta, Tokyo and Manila.

In emergency situations, the need for disaster response and recovery may justify temporarily lifting COVID-19 restrictions. But pandemic measures must be reinstated as soon as possible. Our modelling, pictured below, suggests when COVID restrictions are lifted in response to a disaster, infection rates ascend rapidly.

What can be done?

Potential solutions are more likely to be effective when they involve multiple groups working together. This includes international and local experts, diverse support agencies and affected communities.

Our research identifies ways to improve disaster preparedness and response in a COVID-19 world. They include:

- developing scenarios and forecasts to deal with the interaction of multiple hazards, including COVID-19

- using centrally operating disaster coordination platforms to assist and empower local disaster responders

- evacuation centres that allow for social distancing

- storing supplies of personal protective gear and medical equipment in areas less exposed to natural hazards

- mobile teams of humanitarian workers, volunteers and medical staff that can respond to natural disasters in COVID-affected regions.

Antonio Dasiparu/EPA

Finally, measures must be taken to reduce the risks posed by future disasters. This must be done in culturally informed ways and includes:

- improving land and water management

- land-use planning that considers disaster risk

- urban clean-up after events such as floods.

Such actions are crucial in developing nations such as Timor-Leste, where urban development can amplify natural hazards with tragic results.

Oktoviano Tilman de Jesus, Demetrio Amaral Carvalho and Josh Trindade contributed invaluable expertise to this work.

This article is part of Conversation series on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. Read the rest of the stories here.![]()

Mark Quigley, Associate Professor of Earthquake Science, The University of Melbourne; Andrew King, ARC DECRA fellow, The University of Melbourne; Brendan Duffy, Fellow in Structural Geology and Tectonics, The University of Melbourne; Claire Vincent, Lecturer in Atmospheric Science, The University of Melbourne; Ian Rutherfurd, Professor in Geography, The University of Melbourne; Januka Attanayake, Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne, and Lisa Palmer, Associate Professor, School of Geography, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia: New South Wales Flood Crisis Continues Into Fifth Day

Floods leave a legacy of mental health problems — and disadvantaged people are often hardest hit

Sabrina Pit, Western Sydney UniversityYet again, large swathes of New South Wales are underwater. A week of solid rain has led to floods in the Mid-North Coast, Sydney and the Central Coast, with several areas being evacuated as I write.

As a resident of the NSW Far North Coast, which has had its share of devastating floods, many of the tense scenes on the news are sadly familiar.

Unless you have lived through it, it is hard to understand just how stressful a catastrophic flood can be in the moment of crisis. As research evidence shows, the long term impact on mental health can also be profound. And often it is the most disadvantaged populations that are hardest hit.

Disaster risk and disadvantage

In many places, socio-economic disadvantage and flood risk go hand in hand.

In a study published last year, led by the University Centre for Rural Health in Lismore in close collaboration with the local community, colleagues and I looked at population data following Cyclone Debbie in 2017. We found people living in the Lismore town centre flood footprint experienced significantly higher levels of social vulnerability (when compared to the already highly vulnerable regional population). This study would not have been possible without the support of the Northern Rivers community who responded to the Community Recovery

after Flood survey, nor without the active support, enthusiasm and commitment of the Community Advisory Groups in Lismore and Murwillumbah and community organisations.

Notably, over 80% of people in the 2017 Lismore town centre flood-affected area were living in the lowest socio-economic neighbourhoods. The flood-affected areas of Murwillumbah and Lismore regions included 47% and 60% of residents in the most disadvantaged quintile neighbourhoods.

By examining data from the 45 and Up study, we also showed that participants living in the Lismore town centre flood footprint had significantly higher rates of smoking and alcohol consumption. They were also more likely to have pre-existing mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, as well as poorer general health.

Research from Germany and the US has shown flood risk is often a significant predictor of lower rental and sale prices.

So even before disaster strikes, residents in flood-prone areas may be more likely to battle with financial and health issues. Our study showed disaster affected people also had the fewest resources to recover effectively. When floods arrive, the impact on mental health, in particular, can be acute.

Read more:

Underinsurance is entrenching poverty as the vulnerable are hit hardest by disasters

Floods and mental health

A flood can be extremely stressful in the moment, as one rushes to protect people, property, pets and animals and worries about the damage that may follow. Can you imagine clinging to a rooftop in the rain in the middle of the night and waiting to be rescued?

The damage caused by floods causes enormous financial pain, and can lead to housing vulnerabilities and homelessness, especially for those without insurance — and research reveals a pattern of underinsurance in disadvantaged populations across Australia.

Even if you are lucky enough to have insurance, waiting to have your claim assessed and approved, then dealing with a shortage of tradies can take a real toll on your mental health. The waiting and the uncertainty can be especially hard.

Other flood research by colleagues and I, led by the University Centre for Rural Health, showed business owners whose homes and businesses had flooded were almost 6.5 times more likely to report depressive symptoms. Business owners with insurance disputes were four times more likely to report probable depression.

Flood affected business owners whose income didn’t return to normal within six months were also almost three times more likely to report symptoms of depression.

Lack of income can clearly cause stress for the individual, their family and their larger network. Small businesses play an important role in rural communities and employ a large number of people so the sustainability of local businesses is crucial.

We also found the higher the floodwater was in a person’s business, the more likely the person was to experience depressive symptoms.

People whose business had water above head height in their entire business were four times more likely to report depressive symptoms. Those who had water between knee and head height in their business were almost three times more likely to report probable depression. All this adds up to an increase in mental health issues that often follows a flood.

Six months after the flooding, business owners felt most supported by their local community such as volunteers and neighbours. However, those that felt their needs were not met by the state government and insurance companies were almost three times more likely to report symptoms of depression.

Preparedness and awareness

So, what can be done?

Firstly, we can boost preparedness. Risk and preparedness education may be especially needed for people who have recently moved to flood-prone regions. Many who have moved to regional areas recently may not be aware they live in a flood zone, or understand how fast waters can move and how high they can reach. Education is needed to raise awareness about the dangers. People may need help to prepare a flood plan and know when to leave.

Secondly, supporting people and local businesses after a disaster and assisting the local economy in its recovery could help reduce the mental health burden on people and the business community.

Thirdly, mental health services must be provided. A chaplaincy program was implemented in Lismore by the local government to assist business owners with emotional and psychological support after Cyclone Debbie and ensuing floods. This program was largely well received by business owners for having provided psychological support and raising mental health awareness.

However, the ongoing lack of mental health support remains an issue, especially in rural areas, and is exacerbated by disasters.

Fourthly, insurance disputes and rejection of insurance claims were among the strongest associations with likely depression in our research. We must find ways to improve the insurance process including making it more affordable, improving communication, by making claims easier and faster and boosting people’s understanding of what’s included and excluded from their policy.

No single organisation, government or department can solve these complex problems on their own. Strong partnerships between organisations are crucial and have been shown to work, as is direct and real-time support for flood-affected people.

Read more:

You can’t talk about disaster risk reduction without talking about inequality

This story was updated to add more detail about the author’s research funding, collaborative partners and affiliation. It is part of a series The Conversation is running on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. You can read the rest of the stories here.![]()

Sabrina Pit, Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Sydney, Honorary Adjunct Research Fellow, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drought, fire and flood: how outer urban areas can manage the emergency while reducing future risks

paintings/Shutterstock

Elisa Palazzo, UNSW; Annette Bardsley, University of Adelaide, and David Sanderson, UNSW

First the drought, then bushfires and then flash floods: a chain of extreme events hit Australia hard in recent months. The coronavirus pandemic has only temporarily shifted our attention towards a new emergency, adding yet another risk.

We knew from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that the risk of extreme events was rising. What we perhaps didn’t realise was the high probability of different extreme events hitting one after the other in the same regions. Especially in the fringes of Australian cities, residents are facing new levels of environmental risk, especially from bushfires and floods.

Read more:

Some say we’ve seen bushfires worse than this before. But they’re ignoring a few key facts

But this cycle of devastation is not inevitable if we understand the connections between events and do something about them.

Measures to slow climate change are in the hands of policymakers. But, at the adaptation level, we can still do many things to reduce the impacts of extreme events on our cities.

We can start by increasing our capacity to see these phenomena as one problem to be tackled locally, rather than distinct problems to be addressed centrally. Solutions should be holistic, community-centred and focused on people’s practices and shared responsibilities.

Respond to emergency

We can draw lessons from humanitarian responses to large disasters, including both national and international cases. A recent review of disaster responses in urban areas found several factors are critical for more successful recovery.

One is to prioritise the needs of people themselves. This requires genuine, collaborative engagement. People who have been through a bushfire or flood are not “helpless victims”. They are survivors who need to be supported and listened to, not dictated to, in terms of what they may or may not need.

Another lesson is to link recovery efforts, rather than have individual agencies provide services separately. For instance, an organisation focusing on housing recovery needs to work closely with organisations that are providing water or sanitation. A coordinated approach is more efficient, less wearying on those needing help, and better reflects the interconnected reality of everyday life.

In the aid world this is known as an “area-based” approach. It prioritises efforts that are driven by people demand rather than by the supply available.

A third lesson is give people money, not goods. Money allows people to decide what they really need, rather than rely on the assumptions of others.

As the bushfires have shown, donations of secondhand goods and clothes often turn into piles of unwanted goods. Disposal then becomes a problem in its own right.

Read more:

How to donate to Australian bushfire relief: give money, watch for scams and think long term

Combining local knowledge and engagement

Planning approaches in outer urban areas should be realigned with our current understanding of bushfire and flood risk. This situation is challenging planners to engage with residents in new ways to ensure local needs are met, especially in relation to disaster resilience.

In areas of high bushfire risk, planning needs to connect equally with the full range of locals. Landscape and biodiversity experts, including Indigenous land managers, and emergency managers should work in association with planning processes that welcome input from residents. This approach is highly likely to reduce risks.

Planners have a vital job to create platforms that enable the interplay of ideas, local values and traditional knowledge. Authentic engagement can increase residents’ awareness of environmental hazards. It can also pave the way for specific actions by authorities to reduce risks, such as those undertaken by Country Fire Service community engagement units in South Australia.

Read more:

Rebuilding from the ashes of disaster: this is what Australia can learn from India

Managing water to build bushfire resilience

Regenerating ecosystems by responding to flood risk can be crucial to increase urban and peri-urban resilience while reducing future drought and bushfire impacts.

Research on flood management suggests rainwater must be always seen as a resource, even in the case of extreme events. Sustainable water management through harvesting, retention and reuse can have long-term positive effects in regenerating micro-climates. It is at the base of any action aimed at comprehensively increasing resilience.

Read more:

Design for flooding: how cities can make room for water

In this sense, approaches based on decentralised systems are more effective at countering the risks of drought, fire and flood locally. They consist of small-scale nature-based solutions able to absorb and retain water to reduce flooding. Distributed off-grid systems support water harvesting in rainy seasons and prevent fires during drought by maintaining soil moisture.

Decentralisation also creates opportunities for innovation in the management of urban ecosystems, with responsibility shared among many. Mobile technologies can help communities play an active role in minimising flood impacts at the small scale. Information platforms can also help raise awareness of the links between risks and actions and lead to practical solutions that are within everybody’s reach.

Tailor responses to people and ecosystems

Disrupted ecosystems can make the local impacts of drought, fire and flood worse, but can also play a role in global failures, such as the recent pandemic. It is urgent to define and implement mechanisms to reverse this trend.

Lessons from disaster responses point towards the need to tailor solutions to community needs and local environmental conditions. A few key strategies are emerging:

-

foster networks and coordinated approaches that operate across silos

-

support local and traditional landscape knowledge

-

use information platforms to help people work together to manage risks

-

manage water locally with the support of populations to prevent drought and bushfire.

Recent environmental crises are showing us the way to finally change direction. Safe cities and landscapes can be achieved only by regenerating urban ecosystems while responding to increasing environmental risks through integrated, people-centred actions.![]()

Elisa Palazzo, Urbanist and landscape planner – Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Built Environment, UNSW; Annette Bardsley, Researcher, Department of Geography, Environment and Population, University of Adelaide, and David Sanderson, Professor and Inaugural Judith Neilson Chair in Architecture, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia: Extreme Weather Continues

Australia: Bushfire Crisis (and now Floods)

After the floods come the mosquitoes – but the disease risk is more difficult to predict

Cameron Webb, University of Sydney

We’re often warned to avoid mosquito bites after major flooding events. With more water around, there are likely to be more mosquitoes.

As flood waters recede around Townsville and clean-up efforts continue, the local population will be faced with this prospect over the coming weeks.

But whether a greater number of mosquitoes is likely to lead to an outbreak of mosquito-borne disease is tricky to predict. It depends on a number of factors, including the fate of other wildlife following a disaster of this kind.

Mozzies need water

Mosquitoes lay their eggs in and around water bodies. In the initial stages, baby mosquitoes (or “wrigglers”) need the water to complete their development. During the warmer months, it doesn’t take much longer than a week before they are grown and fly off looking for blood.

So the more water, the more mosquito eggs are laid, and the more mosquitoes end up buzzing about.

But outbreaks of disease carried by mosquitoes are dependent on more than just their presence. Mosquitoes rarely emerge from wetlands infected with pathogens. They typically need to pick them up from biting local wildlife, such as birds or mammals, before they can spread disease to people.

Read more:

The worst year for mosquitoes ever? Here’s how we find out

Mosquitoes and extreme weather events

Historically, major inland flooding events have triggered significant outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease in Australia. These outbreaks have included epidemics of the potentially fatal Murray Valley encephalitis virus. In recent decades, Ross River virus has more commonly been the culprit.

A focal point of the current floods is the Ross River, which runs through Townsville. The Ross River virus was first identified from mosquitoes collected along this waterway. The disease it causes, known as Ross River fever, is diagnosed in around 5,000 Australians every year. The disease isn’t fatal but it can be seriously debilitating.

Cameron Webb (NSW Health Pathology)

In recent years, major outbreaks of Ross River virus have occurred throughout the country. Above average rainfall is likely a driving factor as it boosts both the abundance and diversity of local mosquitoes.

Flooding across Victoria over the 2016-2017 summer produced exceptional increases in mosquitoes and resulted in the state’s largest outbreak of Ross River virus. There were almost 1,700 cases of Ross River virus disease reported there in 2017 compared to an average of around 300 cases annually over the previous 20 years.

Read more:

Explainer: what is Ross River virus?

Despite plagues of mosquitoes taking advantage of flood waters, outbreaks of disease don’t always follow.

Flooding resulting from hurricanes in North America has been associated with increased mosquito populations. After Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana and Mississippi in 2005, there was no evidence of increased mosquito-borne disease. The impact of wind and rain is likely to have adversely impacted local mosquitoes and wildlife, subsequently reducing disease outbreak risk.

From shutterstock.com

Australian studies suggest there’s not always an association between flooding and Ross River virus outbreaks. Outbreaks can be triggered by flooding, but this is not always the case. Where and when the flooding occurs probably plays a major role in determining the likelihood of an outbreak.

The difficulty in predicting outbreaks of Ross River virus disease is that there can be complex biological, environmental and climatic drivers at work. Conditions may be conducive for large mosquito populations, but if the extreme weather events have displaced (or decimated) local wildlife populations, there may be a decreased chance of outbreak.

This may be why historically significant outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease have occurred in inland regions. Water can persist in these regions for longer than coastal areas. This provides opportunities not only for multiple mosquito generations, but also for increasing populations of water birds. These birds can be important carriers of pathogens such as the Murray Valley encephalitis virus.

Read more:

Giant mosquitoes flourish in floodwaters that hurricanes leave behind

In coastal regions like Townsville, where the main concern would be Ross River virus, flood waters may displace the wildlife that carry the virus, such as kangaroos and wallabies. For that reason, the flood waters may actually reduce the initial risk of outbreak.

Protect yourself

There is still much to learn about the ecology of wildlife and their role in driving outbreaks of disease. And with a fear of more frequent and severe extreme weather events in the future, it’s an important area of research.

Although it remains difficult to predict the likelihood of a disease outbreak, there are steps that can be taken to avoid mosquito bites. This will be useful even if just to reduce the nuisance of sustaining bites.

Cover up with long-sleeved shirts and long pants for a physical barrier against mosquito bites and use topical insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Be sure to apply an even coat on all exposed areas of skin for the longest lasting protection.![]()

Cameron Webb, Clinical Lecturer and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Here’s what you need to know about melioidosis, the deadly infection that can spread after floods

Goran Jakus/Shutterstock

Sanjaya Senanayake, Australian National University

The devastating Townsville floods have receded but the clean up is being complicated by the appearance of a serious bacterial infection known as melioidosis. One person has died from melioidosis and nine others have been diagnosed with the disease over the past week.

The bacteria that causes the disease, Burkholderia pseudomallei, is a hardy bug that lives around 30cm deep in clay soil. Events that disturb the soil, such as heavy rains and floods, bring B. pseudomallei to the surface, where it can enter the body through through a small break in the skin (that a person may not even be aware of), or by other means.

Melioidosis may cause an ulcer at that site, and from there, spread to multiple sites in the body via the bloodstream. Alternatively, the bacterium can be inhaled, after which it travels to the lungs, and again may spread via the bloodstream. Less commonly, it’s ingested.

Read more:

(At least) five reasons you should wear gardening gloves

Melioidosis was first identified in the early 20th century among drug users in Myanmar. These days, cases tend to concentrate in Southeast Asia and the top end of northern Australia.

What are the symptoms?

Melioidosis can cause a variety of symptoms, but often presents as a non-specific flu-like illness with fever, headache, cough, shortness of breath, disorientation, and pain in the stomach, muscles or joints.

People with underlying conditions that impair their immune system – such as diabetes, chronic kidney or lung disease, and alcohol use disorder – are more likely to become sick from the infection.

The majority of healthy people infected by melioidosis won’t have any symptoms, but just because you’re healthy, doesn’t mean you’re immune: around 20% of people who become acutely ill with melioidosis have no identifiable risk factors.

People typically become sick between one and 21 days after being infected. But in a minority of cases, this incubation period can be much longer, with one case occurring after 62 years.

How does it make you sick?

While most people who are sick with melioidosis will have an acute illness, lasting a short time, a small number can have a grumbling infection persisting for months.

One of the most common manifestations of melioidosis is infection of the lungs (pneumonia), which can occur either via infection through the skin, or inhalation of B. pseudomallei.

The challenges in treating this organism, though, arise from its ability to form large pockets of pus (abscesses) in virtually any part of the body. Abscesses can be harder to treat with antibiotics alone and may also require drainage by a surgeon or radiologist.

How is it treated?

Thankfully, a number of antibiotics can kill B. pseudomallei. Those recovering from the infection will need to take antibiotics for at least three months to cure it completely.

If you think you might have melioidosis, seek medical attention immediately. A prompt clinical assessment will determine the level of care you need, and allow antibiotic therapy to be started in a timely manner.

Your blood and any obviously infected body fluids (sputum, pus, and so on) will also be tested for B. pseudomallei or other pathogens that may be causing the illness.

While cleaning up after these floods, make sure you wear gloves and boots to minimise the risk of infection through breaks in the skin. This especially applies to people at highest risk of developing melioidosis, namely those with diabetes, alcohol use disorder, chronic kidney disease, and lung disease.

Read more:

Lessons not learned: Darwin’s paying the price after Cyclone Marcus

![]()

Sanjaya Senanayake, Associate Professor of Medicine, Infectious Diseases Physician, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.