C Raina MacIntyre, UNSW; Anne Kavanagh, The University of Melbourne; Eva Segelov, Monash University, and Lisa Jackson Pulver, University of SydneyThe latest New South Wales roadmap to recovery outlines a range of freedoms for fully vaccinated people in the state when 80% of those aged 16 and over are vaccinated.

Unvaccinated people will remain restricted, but will have the same freedoms by December 1, when 90% of adults are expected to be vaccinated.

The relaxing of restrictions will occur in three stages, at the 70%, 80% and 90% vaccination mark, with many restrictions dropped by December 1.

This includes relaxing the 4 square metre density rule to 2 square metres in most indoor venues; and no indoor mask mandates in most venues except public transport, airports and for front-of-house hospitality staff.

The problem is, other countries such as Israel already tried relying mostly on vaccines to relax restrictions – and failed, albeit at lower vaccination levels than NSW is aiming for.

Vaccines alone may not enough to protect against the highly contagious Delta variant.

So who is most vulnerable under the current plan, and how should the NSW reopening plan change to protect these groups and the wider population?

Read more:

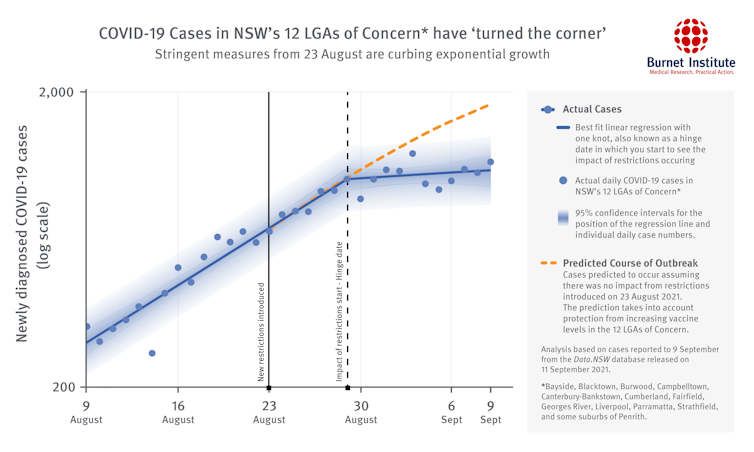

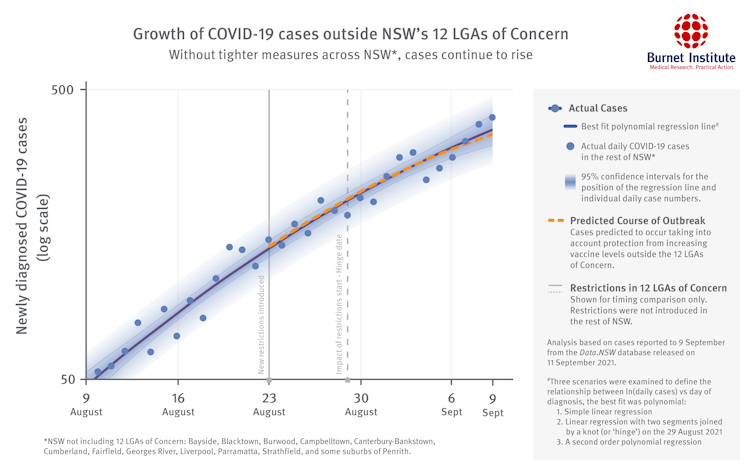

NSW risks a second larger COVID peak by Christmas if it eases restrictions too quickly

Vulnerable group 1: children

About 20% of the population is under 16 years. The 80% adult target corresponds to less than 70% of the whole population, leaving plenty of room for Delta to spread.

One in three children aged 12 to 15 have had a single dose of vaccine, but it may be next year before this age group is fully vaccinated.

Another 1.2 million NSW children under 12 will remain unvaccinated. This is the largest unvaccinated group. With no requirements for unvaccinated primary school children to wear masks, and no plan to ventilate classrooms, outbreaks will almost certainly occur.

Shutterstock

In the US, counties with school mask mandates had much lower rates of COVID in children than counties that did not mandate masks. One unvaccinated teacher who took off her mask to read to a primary school class resulted in 26 people becoming infected.

While children get mild infection compared to adults, around 2% of children who get Delta are hospitalised. Of these, some will require ICU care and a proportion will die. This becomes more apparent when there is high community transmission, and high case numbers in unvaccinated children.

The Doherty report estimates 276,000 Australian children will be infected in the first six months after reopening in the most likely scenario, with 2,400 hospitalisations, 206 ICU admissions and 57 child deaths in that time.

Vulnerable group 2: Aboriginal people

Aboriginal communities in NSW are especially vulnerable to epidemics, contracting COVID and getting severe disease.

There are relatively more children in the under 12 age category in Aboriginal communities, which leaves a much higher proportion of the community unvaccinated.

We saw in the Wilcannia outbreak that a high proportion of cases were in children.

Read more:

COVID in Wilcannia: a national disgrace we all saw coming

Despite this, vaccination rates for Aboriginal communities continue to lag about 20% behind the rest of NSW.

Allowing unrestrained travel into these communities before vaccination rates are high enough to afford protection may be disastrous.

Vulnerable group 3: regional NSW

Remote and regional communities are also vulnerable, because of fewer health services and difficulties with access to care.

An outbreak would disproportionately affect regional NSW.

Vulnerable group 4: people with disability

People with disability, many of whom have significant health conditions, are also at high risk.

Vaccination rates for NSW participants in Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme lag state rates by about 14% despite being prioritised in the national rollout.

In the UK, 58% of COVID deaths in the United Kingdom were among people who had a disability. People with intellectual disability were eight times more likely to die of COVID than the general population.

Vulnerable group 5: people with cancer and other conditions

Adults and children living with cancer and other conditions that suppress the immune system may have a poorer response to COVID vaccines, and may need a third dose.

Read more:

Why is a third COVID-19 vaccine dose important for people who are immunocompromised?

The need for third dose boosters in susceptible people is recognised and programs to deliver these are underway in many countries.

Some are vaccinating specific groups: the United States and United Kingdom are providing boosters to all people 65 and 50 years and over respectively.

Others, such as Israel and many European nations, are starting with older adults and immunosuppressed people, and later including the rest of the population.

Australia is yet to formulate such a plan.

Shutterstock

Children under 12 years with cancer (not yet eligible for vaccination), also deserve to be protected, by vaccines and/or other measures to stop the spread of COVID in the community.

The consequences of overwhelmed health systems on timely diagnoses and treatment of cancer and other serious illness is already being seen in NSW.

A layered plan for a safer reopening

Currently available vaccines alone will not be enough to control Delta. We will need layered protection including safe indoor air, testing, tracing and masks to continue our lives freely when lockdowns lift.

Here’s what we propose:

1. Implement vaccine targets for at-risk groups

We need to make sure no disadvantaged group is left behind, and that vaccine targets are met for all these groups.

For Aboriginal people, we recommend 85-90% targets be met.

For other groups such as people with disability, particularly those living in congregate settings, higher vaccine targets should also be considered.

Read more:

Vaccinations need to reach 90% of First Nations adults and teens to protect vulnerable communities

2. Make indoor air safer

NSW needs a plan to address indoor ventilation, because the virus is airborne.

This has already occurred in Victorian schools, and should be an important part of lifting restrictions in NSW.

Read more:

From vaccination to ventilation: 5 ways to keep kids safe from COVID when schools reopen

The plan should ensure homes, businesses, schools and other public venues have safe indoor air, and that the community is as well informed on safe air as it is on handwashing, so that people are empowered to mitigate risk in their own homes.

3. Maintain high rates of testing and tracing

We must maintain high testing capacity, make rapid antigen testing widely available, and improve contact tracing capacity.

Suggestions of stopping QR code scanning and thereby reducing contact tracing capacity are misguided, and will result in a resurgence of infection.

We do contact tracing routinely for all serious infections such as TB, meningitis and measles, and need to continue this for COVID-19.

4. Plan for booster doses

We also need to address waning immunity from vaccines and be pro-active about booster doses, particularly for those with reduced immunity or who are immunocompromised, and for health care workers.

For the rest of the population, there is enough real-world evidence protection starts to wane as early as five to six months after vaccination.

It is urgent we address this for health workers and other priority groups such as aged care residents, who were mostly vaccinated six months ago or longer. This is not only for their own safety but to prevent health system collapse from under-staffing due to illness or burnout.

Let’s avoid future lockdowns

In the post-lock down world, NSW will likely face a Delta resurgence if multiple restrictions are simultaneously relaxed, as we have seen in countries overseas.

Dropping most restrictions is also likely to result in repeated stop-start lockdown cycles, prompted by health system strain when cases surge.

Only layered, combined protections will provide a chance of safer and sustainable re-opening until we await the promise of second generation vaccines, boosters and smarter vaccine strategies.![]()

C Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Global Biosecurity, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Head, Biosecurity Program, Kirby Institute, UNSW; Anne Kavanagh, Professor of Disability and Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne; Eva Segelov, Professor of Oncology, Monash University, and Lisa Jackson Pulver, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor of Public Health and Epidemiology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.