from shutterstock.com

Naser Ghobadzadeh, Australian Catholic University

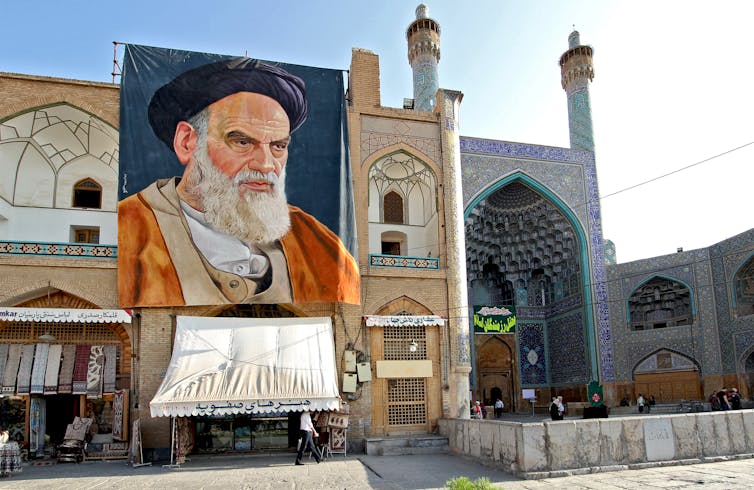

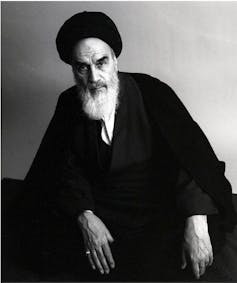

Iran’s ruling clergy are celebrating the 40th anniversary of the 1979 revolution, during which Shi’ite Islamists, led by religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini, toppled Mohammad Reza Shah’s secular monarchy.

The linchpin of the Islamic Republic’s political system is Ayatollah Khomeini’s doctrine of Wilayat-i Faqih, or guardianship of the jurist, which makes a Shia religious jurist the head of state. The jurist’s legitimacy to hold the most powerful position in the state is claimed to be based on divine sovereignty.

As its name suggests, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s current system combines theocratic and republican elements. The president and parliament are democratically elected, while the members of powerful institutions such as the Guardian Council and the judiciary are appointed by the Supreme Leader (Walī-yi Faqīh).

The Guardian Council oversees elections and the final approval of legislation. According to the Constitution of the Islamic Republic, all legislation, policies and programs must be consistent with the observance of Islamic principles.

The Guardian Council has a duty to monitor all legislative decisions and determine whether their implementation would cause a violation.

Read more:

World politics explainer: the Iranian Revolution

This unprecedented political system brought in four decades of internal conflict. The established Islamic Republic of Iran also ceased being a US ally and instead became an enemy. International sanctions, along with the clergy’s mismanagement and endemic corruption, have resulted in a dire economic situation. There is a strong fear the high unemployment and inflation rate will continue to rise.

Under these circumstances, there are now doubts the Islamic Republic can survive. And some wonder whether we may soon see another revolution. So, what is the situation in Iran 40 years after the Shah was overthrown and who is agitating for change?

Decades of unrest

After Ayatollah Khomeini died in 1989, a more conservative Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, came to power and strengthened the theocracy.

The reformist movement emerged in the mid-1990s to counter the newly established conservative regime. They had little chance of gaining power through theocratic institutions, so they focused on the electoral side. They campaigned for women’s rights, democratic rule and a civil-military divide.

Reformists gained power twice: from 1997 to 2005 and from 2013 – with the election of the relatively moderate president, Hassan Rouhani – until now. In these years, reformists controlled electoral institutions such as the presidency and the parliament.

For decades, reformers have struggled to limit the power of theocratic institutions – while still broadly complying by the laws of the clergy, and the principles set in place by Khomeini – and expand the power of republican institutions. However, they were no match for the Khamenei-led resistance, and theocratic institutions are more powerful today than they were in the mid-1990s.

Iran has also continually had tense relations with the international community. In addition to eight years of war with Iraq, Iran has been under sanctions for almost all of the past four decades. These have been imposed by the US, the EU, and the United Nations over claims Iran breached its nuclear obligations.

Read more:

Why the Iran nuclear agreement is a deal worth honouring

Today, the Donald Trump-led US government is pursuing an extremely hostile approach to Iran. Crucially, the US has withdrawn from a nuclear deal negotiated with the Obama administration – under which Iran agreed to limit its nuclear program. The US has reapplied previous sanctions (which were lifted under the deal) and imposed new ones. Iranians are also the most affected of the Muslim majority countries included in Trump’s travel ban.

Reformists have made some progress towards easing economic hardship, loosening social control, and initiating a temporary easing of tensions with the outside community. But the parlous nature of the political structure empowers the theocrats to manipulate the system and stymie any reform effort that promises a path to democratisation.

Reformists or pro-regime opposition

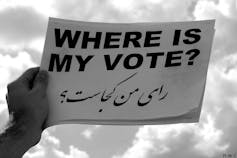

The protests that swept Iran between December 2017 and January 2018 showed that many Iranians don’t consider the reformists capable of bringing about meaningful change. Protestors expressed their anger over increasing economic hardship, as well as Iran’s support and funding for foreign conflicts, namely the civil wars in Yemen and Syria. They also chanted slogans calling for an end to the rule of clerics.

Rampant corruption, the failure of Rouhani to fulfil his promises – such as boosting the economy, extending individual and political freedoms, ensuring equality for women and men, and easing access to the internet – and the return of sanctions have combined to shatter hope of reform. This has been expressed in global protests by the Iranian diaspora calling for a change to the government.

It seems unlikely the reformists will be able to maintain their positions in the country’s electoral institutions. The sad reality is that even if they have another chance, the result will only compound their failures.

Read more:

Why Iran’s protests matter this time

These circumstances have led to another stream of opposition – one agitating for a toppling of the Islamic Republic and regime change – gaining currency. Most members of this group are in exile, including Iran’s ex-prince and son of the Shah overthrown by the revolution, Reza Pahlavi.

But there is profound disagreement between the opposition groups in exile. Although they share a similar goal, they have consistently proven unable to agree on an overarching framework. The profound divisions among the groups has drained both their resources and intellectual capacity, which has rendered them incapable of contesting the country’s ruling clergy.

Those advocating for regime change have also been incapable of articulating a viable alternative to the Islamic Republic. All opposition groups overuse the abstract notion of “secular democracy” without clearly explaining what exactly they have in mind.

Pahlavi’s desire is reportedly not to put himself back on the throne, but to let the people decide what the political system would look like. He has said:

It’s not the form that matters, it’s the content; I believe Iran must be a secular, parliamentary democracy. The final form has to be decided by the people.

While this is a legitimate statement, figures like Pahlavi ought to offer viable alternatives that would help bring opposition groups together. Potential alternatives should also be structured to appeal to the masses, a considerable segment of whom have expressed disillusionment with the ideal of an Islamic state.

Opposition groups are absorbed in delegitimising the Islamic Republic, questioning the way the clergy run the country. In doing so, they forget the the people who have already expressed widespread dissatisfaction with the clergy.

The opposition needs to skilfully craft an alternative to the Islamic Republic and a comprehensive plan for the transition to democracy. Until an alternative political system is formulated and popularised, the opposition will remain impotent and unable to initiate a transformation in the country.

Of course, change is not impossible. A military confrontation with Israel or the US, the departure of 79-year-old Ayatollah Khamenei, or a spontaneous mass uprising could prove a game changer.![]()

Naser Ghobadzadeh, Senior lecturer, National School of Arts, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.