From shutterstock.com

Craig Dalton, University of Newcastle

Over recent months, the news has been saturated with headlines claiming we’re experiencing a “killer flu season”. Researchers watching laboratory data are using the term “flunami”.

Data suggests this is a serious year for the flu, with a higher number of cases, hospitalisations and deaths recorded than at the same time point in previous years. But there’s more to the story.

Increased testing for influenza and a very early start to the flu season have driven these high figures. Meanwhile, we’ve seen heightened community awareness and concern as the media continue to report on the high numbers of flu cases.

Increased concern leads to increased testing

Tragically, influenza causes deaths every year, including among infants and healthy young people. This still comes as a surprise to many. News coverage of these deaths presents human stories that make the risk feel real and threatening.

We can see the impact of this by looking at the trends in Google searches for “flu deaths” and “flu symptoms” in Australia this year. The steep rise is closely aligned with media reporting of deaths from early May.

The Google search interest in deaths in 2019 dwarfs the 2017 interest, when media reports of influenza deaths appeared more sporadically.

The fear of a uniquely severe and dangerous flu season leads more people to go to their GP or emergency department for an assessment if they’re experiencing flu-like symptoms. In turn, it may also lead more doctors to test for influenza, resulting in increased influenza counts.

Every Monday morning in winter our Flutracking survey asks around 45,000 Australians about their influenza-like symptoms (fever and cough). We also ask ill Flutrackers if their doctor tested them for influenza.

Every year, more and more Flutrackers answer yes. Comparing the percentage of Flutrackers with cough and fever who reported being tested for influenza during April and May increased markedly from 2016, with a very significant increase in 2019.

The season is earlier, but it’s not more severe

Since at least 2011, there has been an increasing summer to autumn blip in influenza activity. That trend has been particularly pronounced this year.

Systems like Flutracking are showing higher levels of influenza-like illness for this time of year, but the figures are not nearly as high as the typical August to September peak seen over the last five years.

Flutracking is not perfect, tracking only “influenza-like” symptoms. Influenza surveillance relies on multiple imperfect streams of data; each contribute to our understanding of the whole picture.

Another system providing objective information on the severity of influenza is the New South Wales death registration data. It showed a few unseasonal spikes in February and March, but is otherwise low and around half the rate we see in the middle of a typical influenza season.

Read more:

The 2019 flu shot isn’t perfect – but it’s still our best defence against influenza

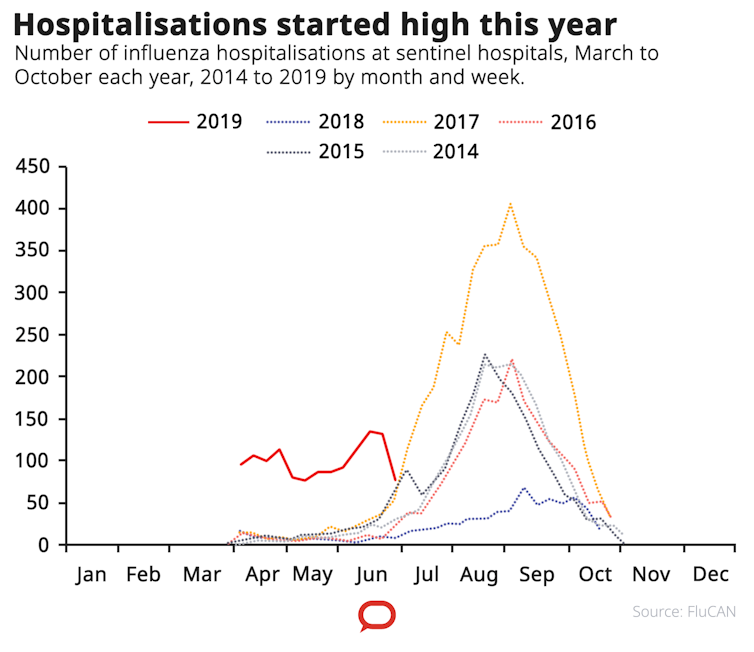

Hospitalisation rates for influenza are high across many hospitals for this time of year, and some may approach peak winter rates seen in 2017. But looking at the proportion of patients admitted to hospital with the flu requiring intensive care, there’s no indication the early influenza season is deadlier than usual.

The simplest way to describe the season is early, but average so far. The rates of influenza are high for this time of year, but the illness is no more severe compared to the typical peak we see in the middle of winter.

Comparing 2019 to 2018, which was a very mild year, further exaggerates the difference.

So when will it end?

In describing the season as “early”, the question arises as to how long it will last. No one knows. The dynamics of an influenza season are a mix of the particular strains circulating, underlying population immunity to the circulating strains from past infection or immunisation, levels of population density and interactions, and weather – all highly unpredictable factors.

If there is no change in the circulating strains then it’s possible the number of susceptible people in the community could be exhausted and the influenza season could “burn out”. If not, it could be a big year for influenza.

Note that this is a broad brush overview of a large country. Western Australia appears to be having a different experience this year with very high rates of laboratory notifications and influenza related hospitalisations. After experiencing a series of mild influenza seasons it may now have a much larger pool of people susceptible to influenza infection.

Read more:

Kids are more vulnerable to the flu – here’s what to look out for this winter

How worried should you be?

So far, the season is early but average. It’s not the worst flu season on record and not a “flunami”.

Is there any harm in the media being hyperbolic about the nature of each flu season? Some see no downside in using media interest as an opportunity to educate the public about influenza or promote research.

At the same time, there is a danger in tying reasonable public health advice to unreliable interpretations of what is actually happening. Crying wolf may undermine trust in public health messaging.

Hopefully, the messages around flu remain clear. You don’t want to get influenza, and if you do get it, you don’t want to spread it to other people. Immunisation, hand hygiene, anti-viral treatment and staying home if ill can all help.

Read more:

Have you noticed Australia’s flu seasons seem to be getting worse? Here’s why

If you would like to help Flutracking track the flu near you, you can join at Flutracking.net.

Sandra Carlson, the Flutracking senior analyst, contributed to this article.![]()

Craig Dalton, Conjoint Senior Lecturer School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.