Dennis Altman, La Trobe University

On November 3, Americans will vote not only for president, but for all members of the House of Representatives, a third of the Senate and a long list of state and local positions.

While the names of Donald Trump, Joe Biden and presumably others appear on the ballot paper, voters actually vote for a list of electors in each state, known as the Electoral College. Their composition is based on the total number of members of Congress from each state: so, California has 55 votes, and seven states plus the District of Columbia have three.

Hillary Clinton’s problem in 2016 was that she won huge majorities in several large states but lost most of the smaller states, which the system slightly favours.

Read more:

Trump can’t delay the election, but he can try to delegitimise it

The electors meet in each state capital and their votes are tallied and reported to a joint sitting of Congress. Members of the college are expected to vote for the candidate on whose list they appear. The Supreme Court has recently ruled to make this mandatory.

Australia borrowed the names of our two parliamentary chambers from the United States. But the crucial difference is that government here is determined by control of the House of Representatives. In the United States, with a separately elected president, Congress is less powerful, and within Congress the Senate is the more significant.

While the representatives are apportioned according to population, each state has two senators who serve for six years. With the power to block legislation and senior executive and judicial appointments, a hostile Senate can make a president impotent in many areas of domestic policy.

In the 1994 mid-term elections, two years into the presidency of Bill Clinton, the Republicans captured both houses of Congress for the first time in 40 years. In the past three decades, there have only been eight years in which the same party has held the presidency, the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Read more:

Trump is struggling against two invisible enemies: the coronavirus and Joe Biden

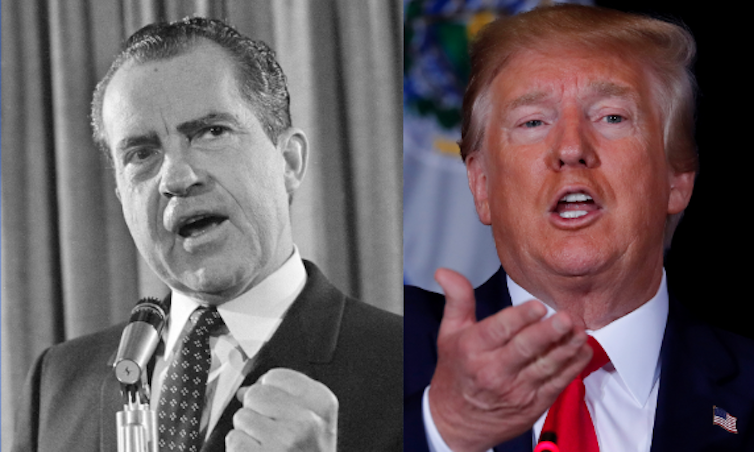

This is not an usual pattern in American politics and, as long as the two parties straddled a wide range of positions, it did not prevent effective government. Members of Congress were expected to vote according to the demands of their constituency, not the party. On crucial issues, such as civil rights legislation or the impeachment of Richard Nixon, they were willing to cross the floor.

However, over the past 30 years, party allegiances have hardened as the centre of gravity in the two parties has polarised. The once-solid Democratic South has become Republican heartland, strengthening an ever-growing right-wing base. Meanwhile, a reaction against the centrist policies of Clinton and Obama has led to a shift to the left by Democrats, causing problems for Democrats from conservative states, such as Senator Doug Jones from Alabama.

Jones is likely to lose a seat he won in a special election because his opponent was an alleged serial sex offender, so the Democrats need to gain five Senate seats to reverse the Republican majority. If the two parties tie, the vice president has a casting vote, which was the case when George W. Bush was elected in 2000. That election marked the start of the “red” versus “blue” state terminology, which in American fashion reversed the usual assumption that blue was the colour of conservatives, red of radicals.

No other Democrat up for re-election looks vulnerable, but there are a number of states where the Republican candidate could lose. The tightest contests are in states that are not solidly red nor blue: Arizona, Colorado, Iowa, Maine and North Carolina.

Evan Vucci/AP/AAP

The stakes are high: in North Carolina almost US$50 million (A$70 million) has been raised so far for the two candidates from the main parties. North Carolina is also a key state for the presidency, which is why the truncated Republican Convention was based there. Like Arizona, it has largely voted Republican over the past 30 years, but rapid population growth is changing party allegiances. It might join Virginia as a former Confederate state now moving back to the Democrats.

The Republicans would need to win 18 seats in the house to regain a majority, which seems unlikely. Individual candidates matter a great deal, but few observers expect more than a handful of seats to change after the Democrats’ mid-term success in 2018.

The greatest problem facing Democrats in November is the systematic way in which Republican state governments have made it more difficult for their opponents to vote. Republican state legislatures have limited the availability of polling stations, made registration more difficult and tightened ID restrictions: in Texas a gun licence is acceptable, but student ID is not. The president is constantly casting doubt over the election, aiming at postal votes in particular.

Few democratic societies have as low a turnout to vote as the United States. The Republicans believe this works in their favour and will do all it takes to keep the figures low.

![]()

Dennis Altman, Professorial Fellow in Human Security, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.