Aerospace Corporation

Melissa de Zwart, University of Adelaide

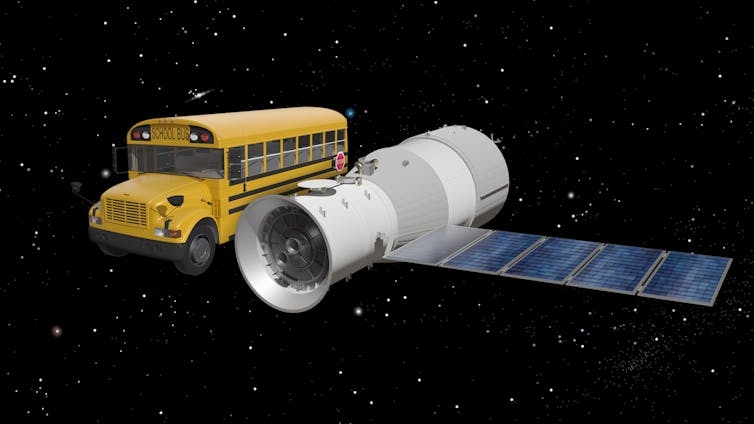

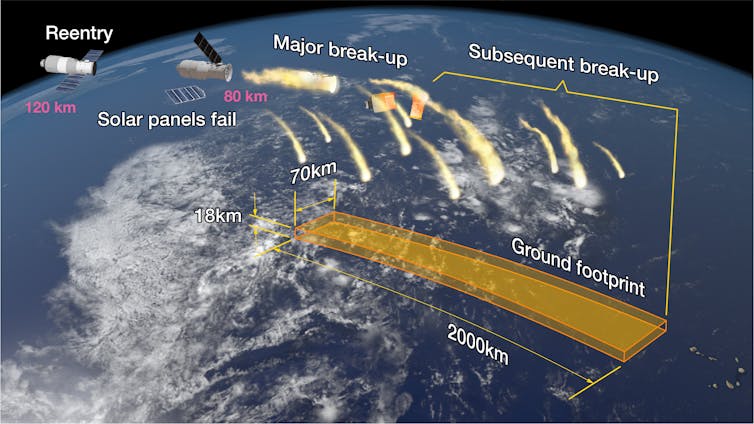

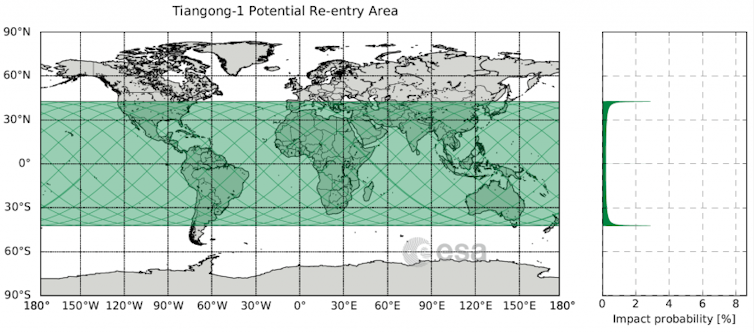

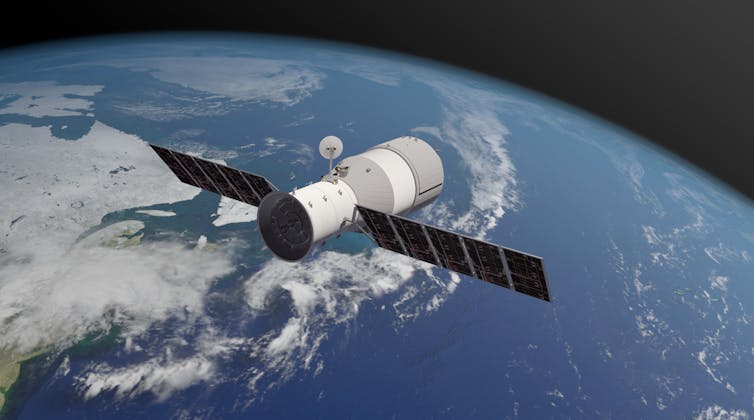

The defunct Chinese space station Tiangong-1 is falling back to Earth and about to crash land some time over the next few days. Most experts expect much of it to burn up as it enters the atmosphere, but it is likely that some pieces of the 8.5-tonne station will survive re-entry.

While the odds of the debris falling on a person are small, you may ask: who is liable in the event of damage caused by a space object to a person or property?

Under international law, a State is liable for damage caused by its “space objects” to another State or its space objects. Liability arises under the provisions of the Outer Space Treaty, which deals both with State responsibility for activities in outer space and the attribution of liability where damage has been caused by a space object.

Read more:

China’s falling space station highlights the problem of space junk crashing to Earth

The Outer Space Treaty is an international agreement, which came into force in October 1967, has more than 100 member countries, including Australia and perhaps more importantly China.

Rules and liability

The Treaty provides the basic rules of use of outer space by nation States. It requires them to carry on activities in the exploration and use of outer space, in accordance with international law and in the interest of promoting international co-operation and understanding.

States who are parties to that Treaty “shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space” regardless of whether those activities are undertaken by or on behalf of the government or by non-government entities.

This is important as it imposes liability on States who are party to the Treaty, rather than the corporations or entities who are launching or operating the space object.

In other words, national governments are responsible to the international community for activities undertaken with respect to space activities by their nationals, whether the launch occurs from that State or not. They are also responsible for launches from their territory by foreign entities.

That means Australia is still responsible for the Australian-built satellites launched last year even though they were launched from Cape Canaveral, in the US.

States will be liable for damage to another State who is party to the Outer Space Treaty caused by the space object or its parts, on Earth and in air and outer space. This includes damage to people, property and corporations.

Damages and compensation

No guidance is given under the Treaty regarding how liability for the damage is to be calculated. But a further treaty, called the Liability Convention, provides some further guidance.

The Liability Convention provides in Article II that a “launching state” will be:

(…) absolutely liable to pay compensation for damage caused by its space object on the surface of the Earth or to aircraft in flight.

This high standard of absolute liability reflects what were perceived by the drafters of the treaty as particularly vulnerable parties. People and property on Earth and aircraft in flight cannot avoid or reduce their potential harm from space from catastrophic launch failure or space debris.

But where damage is caused other than on the surface of the Earth or aircraft in flight the principle of fault is applied. The Convention does not elaborate on how fault is to be determined.

On Earth we are used to applying principles of negligence to accidents involving people or property. Negligence considers issues such as the potential of harm occurring, the foreseeability of that harm and whether sufficient measures were taken to reduce or avoid that harm.

It is not clear if these sorts of calculations exist with respect to space.

What is clear is that the Convention is intended to be “victim-oriented”. Claims for damage may relate to any harm caused by the space object including direct and indirect harm.

Article XII says compensation is to be determined on the basis that it should restore the person:

(…) to the condition which would have existed if the damage had not occurred.

But it wasn’t our fault

What about where objects collide in space causing harm to a third party? In this case liability may be shared by the launching States of the colliding space objects, again in accordance with their respective fault, where the damage is in space, absolutely if the damage is on Earth or an aircraft in flight.

Some exceptions exist where the State making the claim with respect to harm is actually responsible for that harm, through its own gross negligence or an intention to cause harm.

There has only been one claim made under the Liability Convention. The Government of Canada made a CA$6 million claim for compensation to the Soviet Union after its Cosmos 954, a nuclear powered satellite, crashed in Northern Canada on January 24, 1978.

While the final, diplomatically negotiated settlement of CA$3 million, did not specifically mention the Liability Convention, it is generally considered that the settlement was negotiated in the context of the Convention. Those costs related to clean up of the contaminated site in such a remote area.

Read more:

Step up Australia, we need a traffic cop in space

In 1979 debris from NASA’s Skylab fell to Earth in Western Australia. NASA advertised for claims with respect to damage caused by the debris, but no State-based claims were formally made under the Liability Convention.

There were some claims regarding illegal dumping: the local Shire of Esperance issued NASA with a A$400 littering fine. It was eventually paid in 2003 by a US radio presenter and his listeners who raised the funds.

Tiangong-1 was China’s first attempt at a space station. It was launched aboard a Long March 2F/G rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on September 30, 2011, so it is China’s responsibility.

In the unlikely event that a piece of the Tiangong-1 falls on an Australian, the Australian government would need to pursue a claim with respect to any injury the person suffered against the Chinese government. Such a claim could take many years through diplomatic channels.

Unfortunately, an individual cannot make a claim on his or her own behalf.

![]() I therefore suggest that before you get hit by a piece of space junk, you check your health insurance!

I therefore suggest that before you get hit by a piece of space junk, you check your health insurance!

Melissa de Zwart, Professor, Adelaide Law School, University of Adelaide

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.