Seth Lazar, Australian National University and Meru Sheel, Australian National University

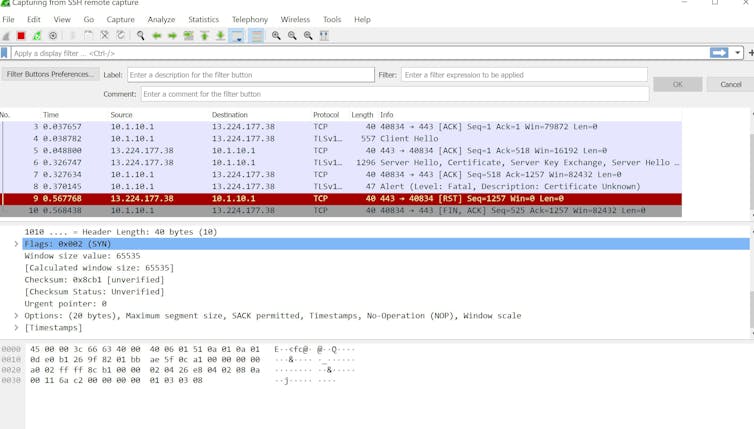

Last week the head of Australia’s Digital Transformation Agency, Randall Brugeaud, told a Senate committee hearing an updated version of Australia’s COVIDSafe contact-tracing app would soon be released. That’s because the current version doesn’t work properly on Apple phones, which restrict background broadcasting of the Bluetooth signals used to tell when phones have been in close proximity.

For Apple to allow the app the Bluetooth access it requires to work properly, the new version will have to comply with a “privacy-preserving contact tracing” protocol designed by Apple and Google.

Unfortunately, the Apple/Google protocol supports a different (and untested) approach to contact tracing. It may do a better job of preserving privacy than the current COVIDSafe model, but has some public health costs.

And, importantly, the requirement to comply with this protocol takes weighty decisions away from a democratically elected government and puts them in the hands of tech companies.

A difficult transition

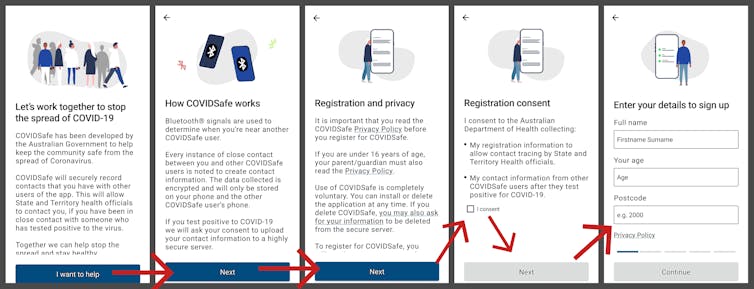

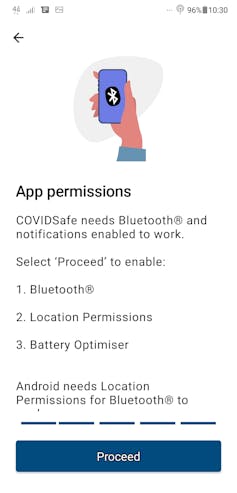

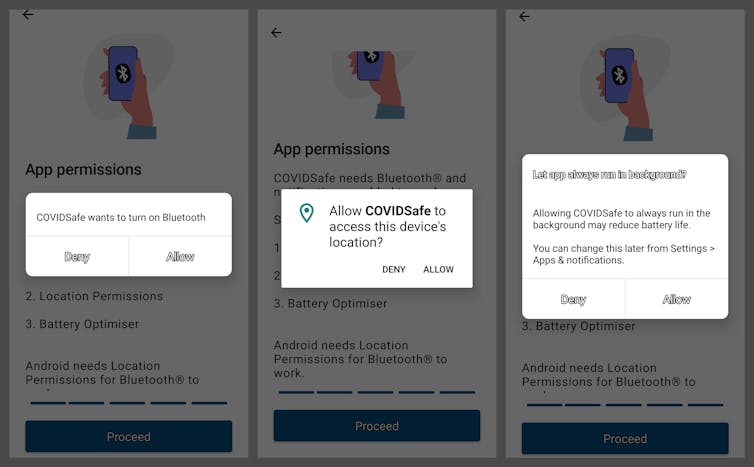

Both COVIDSafe and the new Apple/Google framework track exposure in roughly the same way. They broadcast a “digital handshake” to nearby phones, from which it’s possible to infer how close two users’ devices were, and for how long.

If the devices were closer than 1.5m for 15 minutes or more, that’s considered evidence of “close contact”. To stop the spread of COVID-19, the confirmed close contacts of people who test positive need to self-isolate.

The differences between COVIDSafe’s current approach and the planned Apple/Google framework are in the architecture of the two systems, and to whom they reveal sensitive information. COVIDSafe’s approach is “centralised” and uses a central database to collect some contact information, whereas Apple and Google’s protocol is completely “decentralised”. For the latter, notification of potential exposure to someone who has tested positive is carried out between users alone, with no need for a central database.

Read more:

The COVIDSafe app was just one contact tracing option. These alternatives guarantee more privacy

This provides a significant privacy benefit: a central database would be a target for attackers, and could potentially be misused by law enforcement.

Protecting COVIDSafe’s central database, and ensuring “COVID App Data” is not misused has been the task of the draft legislation currently being considered. However, if the Apple/Google framework is adopted as planned, much of that legislation will become redundant, as there will be no centralised database to protect. Also, since data on users’ devices will be encrypted and inaccessible to health authorities, there’s no risk of it being misused.

Read more:

The COVIDSafe bill doesn’t go far enough to protect our privacy. Here’s what needs to change

For COVIDSafe to comply with the new Apple/Google framework, it would need to be completely rewritten, and the new app would most likely not be interoperable with the current version. This means we’d either have two systems running in parallel, or we’d have to ensure that everyone updates.

Less information for contact tracers

The Apple/Google approach strictly limits the amount of information shared with all parties, including traditional contact tracers.

When a user’s “risk score” exceeds a threshold the app will send them a pop-up. The only information revealed to the user and health authorities will be the date of exposure, its duration, and the strength of the Bluetooth signal at the time. The app would not reveal, to anyone, precisely when a potentially risky encounter occurred, or to whom the user was exposed.

This, again, has privacy benefits, but also public health costs. This kind of “exposure notification” (as Apple and Google call it, though proximity notification might be more accurate) can be used to supplement traditional contact tracing, but it can’t be integrated into it, because it doesn’t entrust contact tracers with sensitive information.

Benefits of traditional methods

As experts have already shown, duration and strength of Bluetooth signals is weak evidence of potentially risky exposure, and can result in both false positives and false negatives.

COVIDSafe’s current approach entrusts human contact tracers with more data than the Apple/Google framework allows – both when, and to whom, the at-risk person was exposed. This enables a more personalised risk assessment, with potentially fewer errors. Contact tracers can help people recall encounters they may otherwise forget, and provide context to information given by the app.

For example, the knowledge that a possible close contact happened when both parties were wearing personal protective equipment might help avoid a false positive. Similarly, learning that someone who tested positive had a close contact with a user, who was with friends who weren’t running the app at the time, might enable us to alert those friends, and so avoid a false negative.

In addition, just having the message come from a human rather than a pop-up might make people more likely to actually self-isolate; we only control the spread if we actually self-isolate when instructed. And, by providing all this data to public health authorities, COVIDSafe’s current approach also grants experts epidemiological insights into the disease.

The two approaches are also supported by different evidence. Apple and Google’s decentralised exposure notification method has never been tried in a pandemic, and is supported by evidence from simulations. However, app-enhanced contact tracing akin to what COVIDSafe does (except using GPS, not Bluetooth) was road-tested in the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, with promising (though inconclusive) results.

Who should decide?

So, should the Australian government comply with Apple and Google’s privacy “laws” and design a new app that’s different from COVIDSafe? Or should Apple update its operating system so COVIDSafe works effectively in the background? Perhaps more importantly, who should decide?

If Apple and Google’s approach achieved the same public health goals as COVIDSafe, but better protected privacy, then – sunk costs notwithstanding – Australia should design a new app to fit with their framework. As we’ve seen, though, the two approaches are genuinely different, with different public health benefits.

If COVIDSafe were likely to lead to violations of fundamental privacy rights, then Apple would be morally entitled to stick to their guns, and continue to restrict it from working in the background. But the current COVIDSafe draft legislation – while not perfect – adequately addresses concerns about how, and by whom, data is collected and accessed. And while COVIDSafe has security flaws, they can be fixed.

Read more:

The COVIDSafe bill doesn’t go far enough to protect our privacy. Here’s what needs to change

Decisions on how to weigh values like privacy and public health should be based on vigorous public debate, and the best advice from experts in relevant fields. Disagreement is inevitable.

But in the end, the decision should be made by those we voted in, and can vote out if they get it wrong. It shouldn’t be in the hands of tech executives outside of the democratic process.![]()

Seth Lazar, Professor, Australian National University and Meru Sheel, Epidemiologist | Senior Research Fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.